In the last two and a half weeks, there have been at least 31 state executions in Iran and a prominent Iranian filmmaker has had his passport seized. The leaders of Iran’s reformist Green Movement remain in jail.

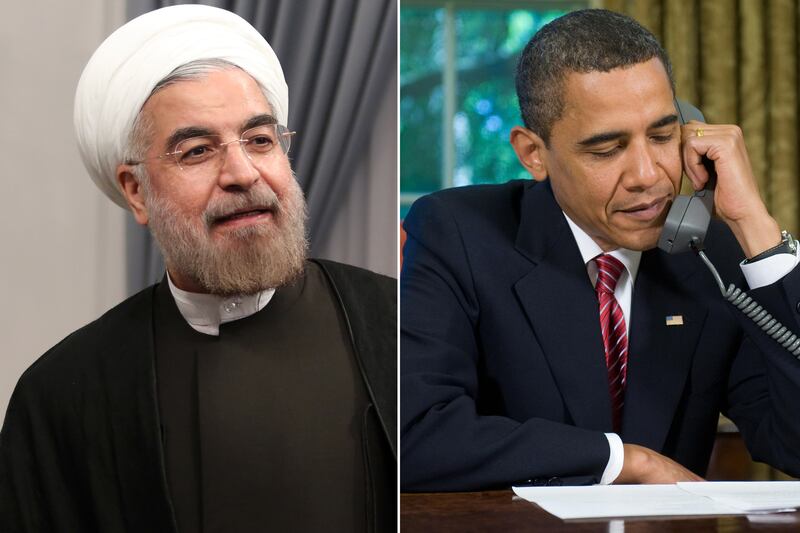

The state of Iran’s civil society in 2013 stands in sharp contrast to the hopes many in the West have placed in the hands of the country’s new president, Hassan Rouhani. On Friday, Rouhani became the first Iranian president to speak directly to a U.S. president since the 1979 Islamic revolution.

To be sure, a handful of activists have been released from Iranian jails in recent weeks. As many as 80 such activists were pardoned this week, according to Iranian media.

Gissou Nia, executive director of the Iran Human Rights Documentation Center at Yale University, said the pardons were a sign that international pressure on the Iranian regime has worked. But she warned against any new negotiations with Iran that do not make human rights a part of the discussions.

As for the pardons announced this week, Nia said the names have yet to be confirmed. “We don’t have concrete data on the identities of many of them, but we believe they were in the Green Movement,” she said, referring to the 2009 coalition of reformers who took to the streets of Iran’s cities to protest what they claimed was an election stolen on behalf of Mahmoud Ahmadinejad, the former mayor of Tehran who has denied the Holocaust and openly expressed support for destroying the state of Israel. Mir Hossein Mousavi and Mehdi Karroubi, the political leaders of the Green Movement who ran in the 2009 election, remain under house arrest to this day.

Nia said her organization has counted 31 recent state executions, according to official and unofficial sources, between Sept. 11 and 25 of this month. Most of the executed were tried for drug trafficking, but she said the justice system did not allow for the condemned to have adequate counsel. In some cases, a group of Sunni Kurds were sentenced to death for “warring with God,” a serious crime in the Islamic Republic of Iran that, in the past, has been used as a pretext to arrest opponents of the regime.

Nia also said she was concerned about reports that Iranian filmmaker Mohammad Rasoulof had his passport confiscated this week and has been asked to report to authorities for questioning on Monday. Rasoulof’s newest film is about a string of murders in the 1990s that were alleged to be at the behest of Iran’s security services.

In the years since 2009, many Green Movement spokesmen said they regarded the Iranian government to be a “coup d’etat” regime. In 2013, however, many Iranians who supported reform voted for Rouhani, who campaigned at the time as a more moderate figure and even said he would release some political prisoners.

In many ways, this was a change of tone for Rouhani. In 1999, for example, when he served on the Supreme National Security Council, Rouhani authorized state security forces to arrest student leaders who had organized demonstrations at Tehran University. “This is the end of reform,” Saeed Ghasseminejad told The Daily Beast. He spent four months at Iran’s Evin prison in 2003 after organizing protests at Tehran University; today, Ghasseminejad is a doctoral student at the City University of New York. While he acknowledged that reformers in Iran supported Rouhani, he also said there were no real reformers in his cabinet and that Rouhani was responsible for sidelining previous attempts at change in the 1990s and 2000s.

Indeed, Ghasseminejad pointed out that Rouhani’s justice minister, Mostafa Pourmohammadi, sat on a judiciary panel in 1988 that sentenced thousands of alleged traitors to death at the end of the Iran-Iraq War. Ghasseminejad said many Iranians today regard Pourmohammadi “as a murderer” for his role in the purge of 1988.