One of my favorite quotations is oneattributed to the French thinker Jean Baudrillard. “Once you arefree, you must ask who you are.” This is true, I think, forindividuals, groups, and nation-states—including the Jewish people,in our founding myth of Exodus followed by Sinai. At first, we areadolescents, yearning only for release from bondage to others. Butthen, finally, we’re free. And then what?

The “pro-Israel, pro-peace”organization J Street—at whose conference I and other key OpenZion contributors, most importantly Peter Beinart, haveoccasionally spoken—likewise seems in that awkward-in-between stagebetween youth and identity crisis.

For several years, J Street’smessage—even its slogan—elicited the basic response of “Huh?” Huh? You’re pro-Israel but you oppose the occupation? Huh? You’re Jews but you have more solidarity with Palestinians thanwith Jewish fundamentalists? Wait, you’re against Israeli policiesbecause of your Jewish values?

By now, I think all of these yes-butsare banal. We’re here, we’re pro-Israel/pro-peace, and we’reall used to it. Sure, at some synagogues in the heartland, J Streetis still treif. But at its conference this year (3,000attendees strong), there was much less talk than in past years offinding our voice, balancing our various commitments, and otherwisesquaring the circle of non-domination Zionism. Indeed, it was notPeter Beinart but Likud stalwart Tzachi Hanegbi who saidthat J Street’s legitimacy is not an issue.

And then what?

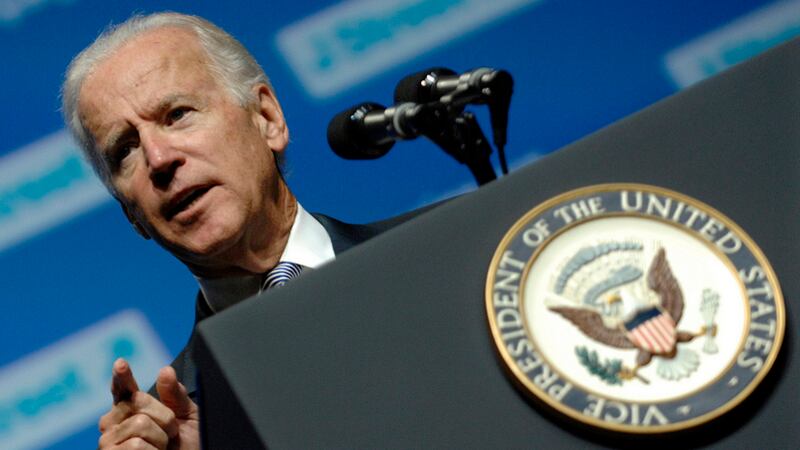

Having established itself as a DCplayer—still a junior player, perhaps, but enough of one to featurethe American Vice President at its conference—the question now iswhat, exactly, J Street is playing for. There are at least twoanswers to that, and they point in different directions. Either JStreet is essentially a single-issue organization, focused on thetwo-state solution for Israel and Palestine, or it is ageneral-interest pro-Israel, pro-peace organization, focusedprimarily on the two state solution but with a general set of valuesthat dictate other positions as well.

In practice, J Street has been a littlebit of both, with an emphasis on the former. But the positions aredrifting apart—and each has its costs and benefits.

Certainly, the two-state solution iswhat motivates J Street’s members. I watched participants doze offduring Vice President Biden’s keynote address, during which he tookhis audience on a panoramic tour of the Middle East (he talked aboutYemen, for God’s sake, before finally getting around to Palestine), various left-wingers’ statements on social issues, inequality, andso on. Except for the two-state solution, the only issue thatreliably drew applause was religious pluralism in Israel. And thisin the context, need we even remember, of shifting landscapes inSyria, Egypt, and Iran.

There are many reasons for this. First, the Israeli leadership has said “not now” for years, andthe Left has grown suspicious. Second, there’s not that muchdaylight between the Left and the Right on issues like Iran, savethat the Right is more suspicious than the Left (or the Left is morenaïve). Third, the hard core of J Street remains peaceniks:old-time hippies, new-school student activists, and everyone inbetween, it’s peace that J Street is about, and that means peacewith Palestinians.

J Street’s own organizationalpriorities have followed suit. Notwithstanding the summer fires inthe wake of the Arab Spring, JStreet is launching its “2 Campaign,” to garner support forthe two-state solution as Secretary of State John Kerry attempts tojumpstart negotiations. Indeed, the conference was told, now isprecisely the opportunity for peace.

Well, sure, but not really, right? Perhaps this is the moment of opportunity, or perhaps it isn’t. But J Street is saying that it is because it is focused on keepingthis issue (dream?) alive.

So far, when the conversation wandersoff-topic, J Street seems to wander as well. The organization hasduly issued statements regarding Syria, Iran, and Egypt, but they’remore reactive than pro-active. AIPAC’s hawkish values are clearand touch every aspect of Israel’s perceived needs. J Street’smore dovish ones are tentative by comparison.

Such focus is not necessarily a badthing. In the world of LGBT activism, where I spend much of my time,there’s widespread agreement that—for better or for worse—thelaser-focused organization Freedom to Marry has been more successfulin its work than more general organizations like the Human RightsCampaign. At the same time, HRC is more sustainable, and speaks (orpurports to speak) to a deeper set of values and issues.

So which is J Street: Freedom to Marry,or HRC?

That the organization is even havingthis conversation is, itself, a sign of success. J Streeters are outof their awkward adolescence, and know how to respond to the JewishRight and to the Campus Left. They are more confident and betterinformed than they were. They know that, in the words of veteranpeace activist Rabbi Chaim Seidler-Feller, it’s up to thepro-Israel, pro-peace camp to distinguish between Hebron and Haifa,since neither the far right nor the far left is willing to do so. They know that there are one-staters on both sides, and that thetwo-state solution is losing its sense of inevitability. They knowthat they’re going to be called traitors and self-haters—andthey’re ready for the fight.

As someone who supports this basicagenda, I am heartened to see this maturation, and the shift in powerthat has come with it. J Street is already entitled to a littleself-congratulation. But then again, Jews complained about the foodwithin a week of the parting of the Red Sea. What was it that theFrench philosopher said? As soon as you’re free, you must begin tokvetch.