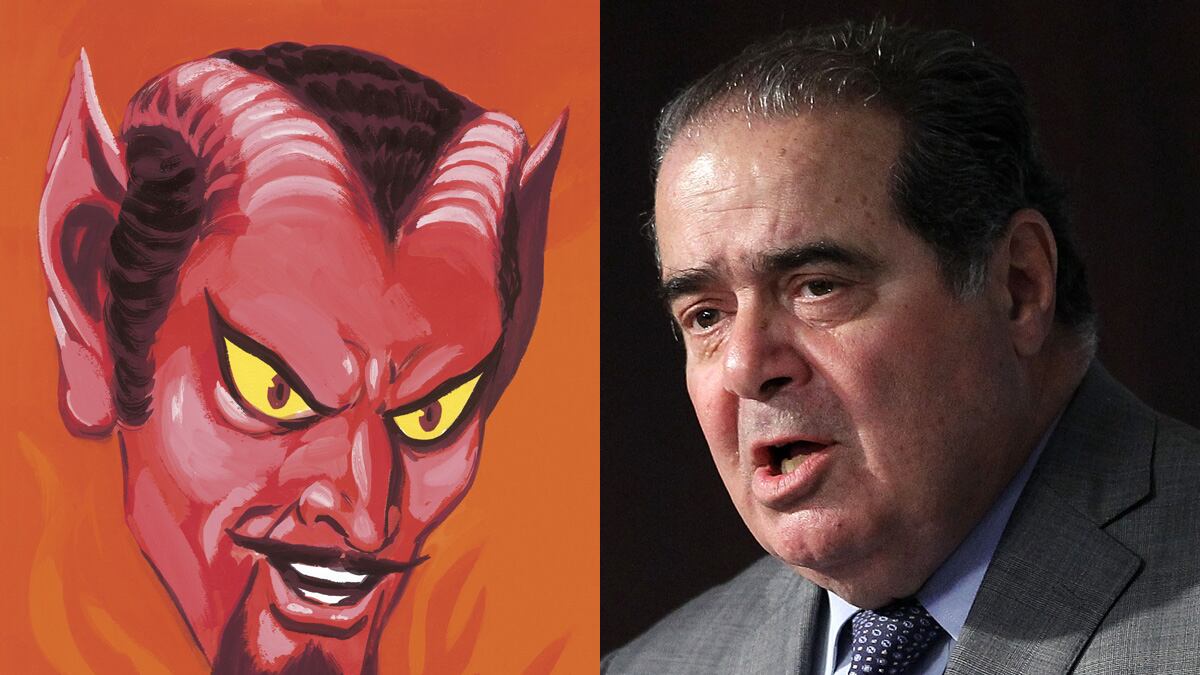

In an interview in New York Magazine, Supreme Court Justice Antonin Scalia declared that he believes the Devil is a “real person.” Scalia went on to say—in a statement reminiscent of Baudelaire and The Usual Suspects—that the Devil is actively engaged in “getting people not to believe in him or in God. He’s much more successful that way.”

Many, like Scalia’s interviewer, were surprised by his boldness. But the feisty and controversial Justice is on sure footing when he says that this is “standard Catholic doctrine.” In August, Minneapolis and St. Paul Archbishop John Nienstedt stated that gay marriage, condoms, and pornography are the work of the “Father of Lies.” Even Liberal favorite Pope Francis has spoken about the Devil and is rumored to have performed a public exorcism back in May.

It’s not only Catholics who believe in Satan. Scalia is correct when he says that most people agree with him. A 2007 Gallup Poll revealed that 70% of Americans believe in the Devil and a separate 2013 YouGov survey (PDF) suggests that more Protestants than Catholics are devil-fearers. The influence of the Devil is pervasive. Some American evangelicals export teen exorcists to the UK to fight the Harry Potter induced demonic infestation there. And Katy Perry reminisced in an interview that Dirt Devil vacuum cleaners were not permitted in her evangelical household because of their demonic connotations.

Between sponsoring state legislatures, co-authoring books with J. K. Rowling, and investing in Trojan, Satan has been busy. But who is the Devil and what do Christians really believe about him?

Unlike in the movies, the Biblical Devil is a touch anemic. He’s a bit player in the Old Testament; readers of Genesis will find neither apples nor Satan in the Garden of Eden. The smart-talking serpent wasn’t identified as the Devil until centuries later. Satan’s first cameo, in the book of Job, casts him as a trickster-cum-lawyer who is close enough to God to enter into a wager about the piety of Job.

Demons are more regular guest stars in the New Testament. While ancient Greeks and Romans thought daemons were ambiguous supernatural entities, those that appear in the Gospels are antagonistic. They possess the bodies of hapless ancient Mediterraneans, align against Jesus and his followers, send a herd of pork chops off a cliff, and steel themselves for a showdown at the end of the world.

None of that seems to go on today. As Scalia puts it, the Devil has gotten “wilier.” In an effort to stay one step ahead, priests gather every year at the Ateneo Pontifical Institute in Rome to swap stories and to learn the most up-to-date strategies in spiritual warfare. (Full disclosure: I attended the 2012 course.) Enrollment in these classes grows larger each year and Catholic dioceses in the US report a marked increase in requests for exorcism from their congregants.

The course teaches that Devilish influence in the world is of two basic types. The first is standard stuff. Tempted by the second helping of cake, the only-marginally-reduced Jimmy Choos, or the bouncy intern who really “gets” you? That’s Satan. But the second type, “extraordinary” machinations of the devil, plunge us deeply into the supernatural.

On a sliding scale of bad to worse, common to rare, the Devil can possess places and objects, cause illness, or create “vexations” in a person’s life. A person can be “obsessed,” meaning he or she is preoccupied with feelings of worthlessness or thoughts of suicide. Worst of all, a person can be possessed by a demon or the Devil himself, Exorcist style.

Very few people strike Faustian deals with the Devil. After all, trading sixty years of power and fame for an eternity in hell is just poor investing. How, then, does a person let the Devil into their life? According to the exorcists, risky behaviors include: general temptation, drug use, listening to heavy metal, reading books about teen wizards, watching pornography, consulting horoscopes, and practicing yoga.

The trouble is you might not know you’re possessed. One exorcist relayed an anecdote about exorcising a 40—year-old man. Unbeknownst to him, the patient had been possessed since he was in the womb. The only symptoms of his condition were his doubts about God and an obsession with ‘self-gratification.’

This could be more widespread than previously recognized.

It all seems like superstition, but it’s worth noting that almost all teachings about the Devil are Biblically based. The idea that God fights Satan is both ancient and internally consistent. If the world is the playing field for the contest between good and evil, then it stands to reason that any perspective, viewpoint, or consumer product not from God fights for the other side. There’s no fluffy “room for dialogue” here, either. Satan isn’t a mixed-up teen yearning to be understood. Once you’re inside it the system makes sense. Eat angel food cake, not Devil Dogs.

When it comes to people, though, discerning demonic influence is more difficult. According to contemporary Roman Catholic theory, the only sure signs of possession are superhuman strength, the ability to speak unlearned languages, flying, and knowledge of people’s thoughts and secrets (skills that in other contexts sound pretty fantastic).

But most do not manifest these superpowers in their everyday lives. And while worldly success sometimes has a whiff of demonic patronage, identification is dangerous. As David Frankfurter’s Evil Incarnate shows, the accusation of demonic conspiracy is one of the most potent forms of Christian slander. Just ask midwives, medieval Jews, or inhabitants of Salem, Mass.

Scalia wisely refrained from identifying any group as participants in the Devil’s work. Those who would try should note that in the past two millennia individuals accused of being either the Antichrist or possessed by a demon include Martin Luther, Ronald Reagan, Britney Spears, Barack Obama, and Jesus of Nazareth. Fighting the good fight runs some risk of embarrassment.