For a young man growing up in the Netherlands in the 1950s the War—that is the Second World War—hung like smoke. It was everywhere: “We grew up with the notion that you couldn’t go shopping in certain shop butcher shop because he had been a collaborator or buy candy at a certain tobacconist because she’d had a German boyfriend during the War. My primary school teachers all had fantastic tales of derring-do—invariably all fake.”

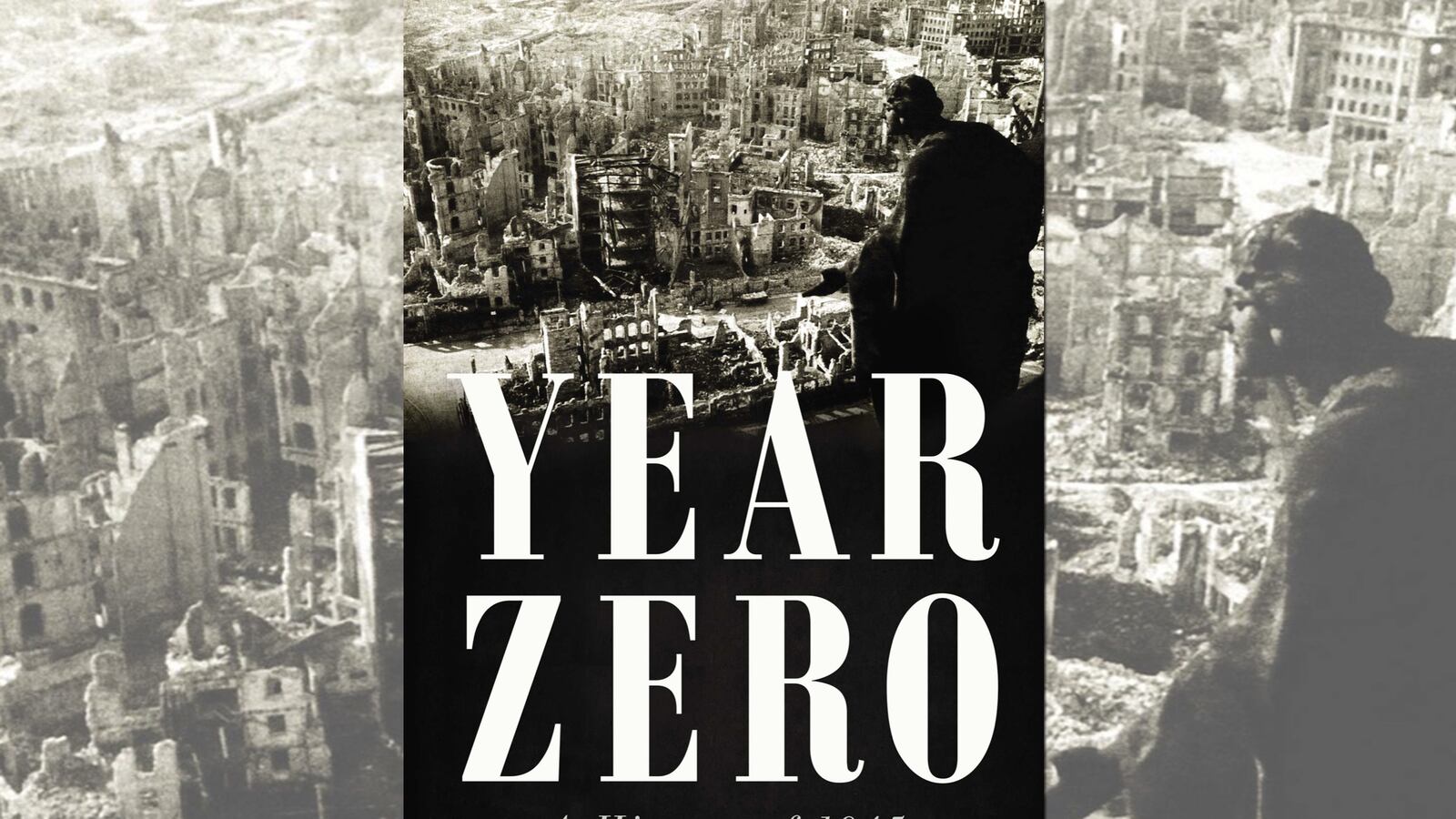

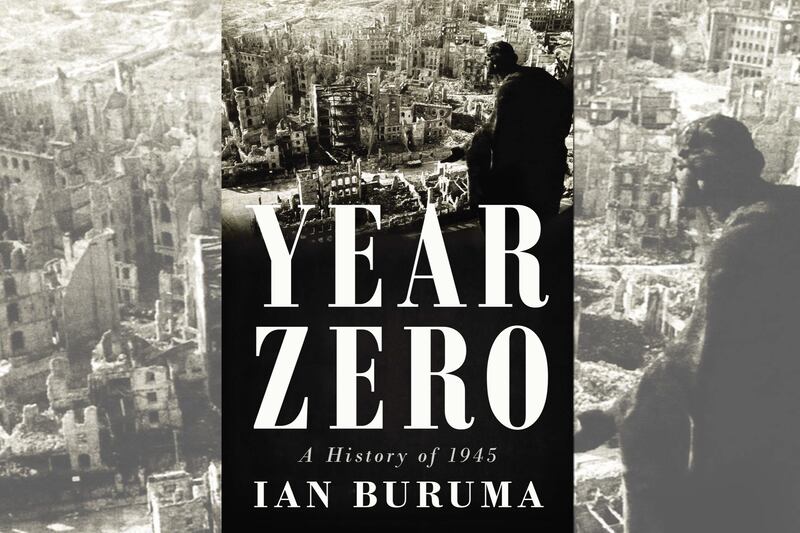

Out of this experience comes Year Zero, Ian Buruma’s global tour of what the world looked like in 1945 as peace descended. Peace will seem a funny idea within a few pages of Buruma’s book. For what Europe, Japan, Indonesia, China, and many other countries experienced in the first months of “peace” was anything but. The bombs had stopped filling the sky with their terrible whistle, but new sounds replaced them—the cries of hungry children, the screams of raped women, the pleas of survivors, the single shots of executions, the scissors against the scalp of a collaborator, and the shuffle of millions on the march.

This is no boy’s story, no comic book, no Spielberg heroics, no Stephen Ambrose march of good boys doing the hard stuff. It is a carefully written and cleverly organized (around themes rather than countries) account of revenge, horror, evil, symbolic justice, and the beginning of something we now know as our modern world. Reading it one has the experience of finding out your mother isn’t your mother, that the assumptions you had safely made about the world are no longer true.

Like many I was taught tidy dates in school—the Civil War (1861-1865), the French Revolution (1789), the First World War (1914-1918), the Second World War (1939-1945)—but bow-tied history isn’t real history, and one of the most important lessons of Buruma’s book is to make one reach for your textbook and erase that “5.” I’m not sure what number to put there instead, but to say the war ended in that year is impossible. Instead, its effects—both the clearly physical and shadowy mental—lingered for years, decades. Buruma says that the echoes of the war can still be heard today, in, say, the philo-Semitism of the young and hip in Warsaw who sport Stars of David and form klezmer bands. What a strange echo it is.

But let’s not take too many lessons from Buruma’s book; he wouldn’t want us to. He resists the way that history is so easily and carelessly bandied about by politicians (see John Kerry invoking Chamberlain and Munich 1938 to argue for intervention in Syria) and used to explain the present or predict the future. Let’s instead look for contours and whispers, for the way the past creeps into the present. And, thankfully, for us he has delivered book that is very much of our time (more on that in a moment) but also one that is sensitive to history, to its horrors and triumphs. Not for him the Brokaw-ization of the “Greatest Generation.” Though he’s still a sentimentalist, put on The Longest Day (that schlock masterpiece you probably watched with your grandfather—I did—on repeat) and he’ll give a tear or two when the Scottish bagpiper (Bill Millin was his name) blows his away across Sword Beach.

It was another war, a recent one, that first made Buruma turn to this subject, an idea that had “been in his head longer than it took to write.” As he told me over tea one recent morning, “Nobody has really looked at what happened immediately after World War Two. I suppose one of the reasons I thought of that was because of Iraq and all that, because we have a generation of leaders who have no experience with war at all. Who rather blithely talk about projecting force without really thinking about what happens after [they invade].” In the lead up to the U.S. invasion of Iraq, President Bush and his war cabinet were eager to point to the U.S. success in rebuilding Germany and Japan after World War Two as a promise of what would happen again. Rubbish: “A perfect example of historical ignorance.”

Are there any lessons from history? “People either take the wrong lessons assuming that things are always going to be repeated in the same way, which they never are. Or there is a sentimentality—if only everyone knew the horrors of Hiroshima then we’d never go to war again, which of course isn’t true. I’m very skeptical of learning lessons. But I would never say that history is useless because without we don’t understand ourselves and our own time.” And we certainly can’t understand the European Union, Japan, and a dozen other countries without carefully understanding their experience during and after the war.

But nor could one entirely imagining the world today from the vantage point of 1945. The European Union and Europe’s great social democracies were about to come, borne of the rubble, but conceived earlier while the Nazis still reigned. “The idealism and the optimism that was also part of 1945—social democracy, equality, international organization—were ideas that people had been thinking about before. If you look at the underground press in occupied countries there’s an awful lot of discussion about what the world should be after the war, and very largely quite left-wing. The ideas weren’t new. The one good thing to be said about human beings is that they’re very creative after destruction—and the destruction of WWII gave a huge impetus to building institutions in the hope that we could build a better world.” Though, of course, much of that promise and optimism petered out—see in America the Civil Rights movement and the Great Society versus the Tea Party today; in Europe see the technocratic elitist vision of the EU versus the dysfunctional, anti-democratic organization today.

As for the 1960s, if you want to understand the iconic student protests and the social change they wrought, you have to understand what the students were really protesting. “If you think about the student protest movements in the ‘60s, especially in Germany and Italy and Japan—how closely linked it was to WWII memories. Not for nothing did the students call the riot cops the SS. The old order was associated often with fascism, usually unfairly but it was. There was a strong notion that the parents’ generation hadn’t been honest—it was beginning to be clear then that all the old stories we were told at primary school about everybody being a resistor were completely untrue. And that real resistance was fairly rare as was real collaboration, and that most people just tried to keep their nose clear. That become obvious to most people in the 60s, just as the Holocaust was only rarely discussed. And that was in many ways why the student movement began. They were responding to that amnesia—our parents looked the other way. We have to be active, we have to stop the Vietnam War, we have to be resistors. To be reductionist, the 1960s student protests can be explained by the birth control pill and the delayed reaction to World War Two.”

One of the most striking parts of Buruma’s book, which he deals with better than anyone else I have read on the subject, is the erotics of liberation—the orgasmic exultation at being rescued and having survived the brutal penetration of their conquerors. The way Dutch, French, and even German women threw themselves with frank abandon on the “rich, tall, blonde” Americans, and the way the Soviet army raped its way across Germany. Foucault and Freud (and maybe Margaret Mead) should both be consulted on the complex sexual dynamics at play here.

For Buruma the mass of sexual release—wanted and unwanted—in the wake of the war is the starting point for understanding his subject. “Sex is very largely about power, power relations—the occupation after conquering a country. The masculine conqueror penetrating the feminine defeated. That was very much the mood during the War when defeatist French intellectuals described France as effete and the German occupiers as vital. And it was like that after liberation, too.” And so, female collaborators were shorn of hair and desexualized while other women hopped into the arms of the Americans, or if none were available than the somewhat duller Canadians. But let’s be clear, this was not some Boogie Nights-style orgy. For many women it was about survival—especially in devastated Japan and Germany where American soldiers meant food and money. Meanwhile the Russians enacted a mass, frenzied vengeance against German women that was a sickening manifestation of the Revolution’s hammer.

Despite the total violence of the war, revenge between former adversaries was relatively rare (with the notable exception of the mass expulsion of ethnic Germans from Czechoslovakia and other countries), but bare-knuckle vengeance was largely absent. Why? “If you look at patterns of revenge, they’re very rarely against the former enemy. They are often against the collaborators amongst your own people or minorities who are associated with them. The animus is much greater. Once your enemy has been defeated, they were the enemy, OK, but your own people—the traitors—are the one you really want to get. People will come to terms with the old enemy, nobody blinks an eyelid anymore if at a commemoration if you have Germans—Kohl and Mitterand holding hands at the war cemetery. But that kind of reconciliation with a former collaborationist leader was unthinkable.”

And what of anti-Semitism which persisted even as the Jewish survivors were being released from the soon-to-be infamous camps. “There was a toxic mixture of anti-Semitic propaganda by the Nazis. It sticks to some extent, it made that social anti-Semitism that was everywhere before the war worse. There was also that sense of guilt of letting this happen to your own citizens, which never makes the victims popular. There’s a famous line by a German-Jewish journalist, that the Germans will never forgive us for Auschwitz.”

Back to the instigators of the war, one question throughout Buruma’s book is which of them, between Japan and Germany, got it right? Who best dealt with their culpability and crimes during the war? “The Germany that supposedly got it right was West Germany. East Germany didn’t really deal with it because they were part of the Soviet system, the victors. But West Germany only began to deal with the Holocaust in the 1960s, in some ways the Japanese were ahead of them in the 1950s. The difference really is the Holocaust; the Nazi regime took over in a kind of coup. That was very easy to separate. Japan had continuity—it was largely an imperial war—and the Emperor remained. And it became completely politicized, because after the war the Americans wrote a new constitution, with that famous article about pacifism. The argument for that was largely supported by the left who said Japan needs this or otherwise we’ll become militarized again—look at what happened in World War Two. Those on the right said, yes, it was a terrible war but we didn’t do anything that other nations haven’t done. Why should we be ashamed of ourselves? It’s all left-wing propaganda. There was no consensus.”

“Unlike in German, where it was very easy to have a consensus that Hitler was a bad thing and that exterminating the Jews was a bad thing. People who disagreed with this were a lunatic fringe.” That excuse, of course, helped large parts of German society, such as prominent industrialists, say it wasn’t their fault, that they had had no choice but to go along with the madness.

And so many of the old elites in Germany remained. And here emerges another parallel with Iraq: “If you conquer a country and the war comes to an end, how do you run them without the elites? They were the bureaucracy—they had run the ministries, the universities. Cut them all out and you have chaos. They needed a lot of those people in Germany and Japan. So that meant that you were stuck with a lot of people with blood on their hands. They other thing that German President Konrad Adenauer was very conscious of was that people were very keen not to repeat the mistakes of 1918—the UN had to be different than the League of Nations, you couldn’t have a repeat of Versailles which had humiliated the enemy. Adenauer was very conscious of the dangers of driving the old Nazi elites into a kind of revanchist underground. And he wanted to incorporate as many of those people into the new order. It was a sensible decision but to grow up in a country like that surrounded by people with that kind of past for a new generation as very demoralizing. It wasn’t’ for nothing that in the 1970s the most violent left-wing splinter groups came from Japan and Italy and Germany—because they grew up with professors who had been Nazis and fascists and now suddenly they felt they had to resist.”

And what of that hoary old cliché, time heals all wounds? Which seems true in Europe today. “It’s so difficult to say. On the surface it would seem to be that way. I was in Vietnam 2 years and you walk through Saigon and the average age is 25 and nobody has any memories. You would think that history doesn’t leave traces, and yet when you read about what happened in certain societies—China, Poland—where everything was torn apart. You wonder if that doesn’t leave traces, it must do. For example the third generation of young poles playing klezmer music, rather self-consciously, is a trace. And the relations between Poles and Jews can’t be normal, they can be friends but there’s an edge there. So I think history does leave traces but it’s just not always obvious.”

Even in America we’re not free of history: “The obstruction of the Tea Party in Congress is not completely unrelated to the Civil War. Most of them are from the south, there are lingering resentments that go back to then.”

But, “By and large, it’s true in Western Europe that a lot of the old wounds have been healed, but it’s only recently that most Europeans don’t mind when Germany wins a soccer game.”

“When there is a conflict somewhere and people in the west feel they should get involved in it, the fact that no one expects the largest country in Europe to take any part shows that the memories are still there. It’s not because other Europeans would be spooked but it’s the Germans themselves who don’t want to.”

Whether the memories will disappear in succeeding generations, Buruma only says, “Maybe.” And wrapped in the ghost of history, we part ways in the bright New York sunshine.