If you’ve been paying attention to the recent spate of news-making media appearances, you know we’re supposed to take Russell Brand seriously. It’s actually a good idea: Brand is smart, engaging and politically informed. His curious brand of celebrity radicalism won't succeed at transforming American politics where Obama (and so many others) have failed. But it might just help us where we need it most.

Like most people we are invited to take seriously, it has been a really good couple of months for Russell Brand. Surprisingly and delightfully, he has rocketed to newfound fame not by taking himself more seriously, but by devoting his life to matters deeper than Arthur or Katy Perry. Moved and touched by the prospect of radical politics, he edited an issue of Britain's New Statesman magazine, released last Wednesday, that includes his own 4500-word manifesto. He publicly criticized Hugo Boss for dressing the Nazis (and was purged for this dire offense from all things GQ). He appeared on the MSNBC show co-hosted by Mika Brzezinski, depicting it as an infantile puppet show, revealing that even media figures can be liberated by the imprisonment of vapid fame.

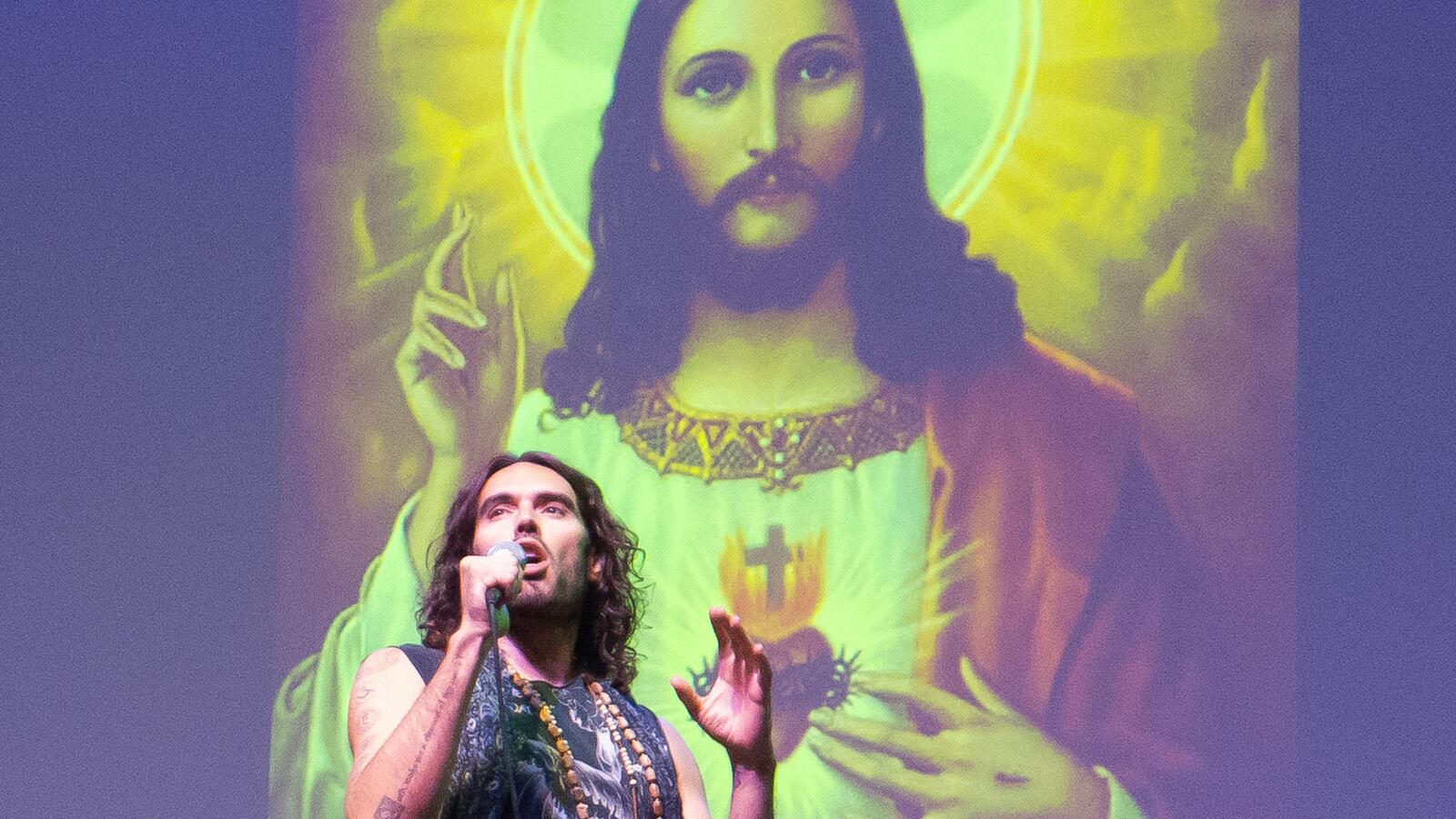

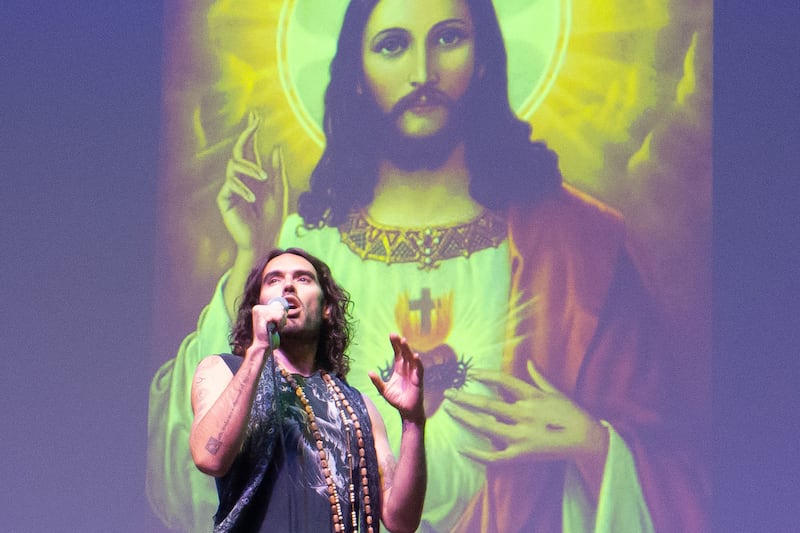

But before he did any of these things, Brand had a sadly ill-fated program of his own, the cable talk show Brand X, canceled just this summer. The microscopic pool of politically-minded people in Los Angeles being what it is, when the producers of Brand X sought out a passably non-liberal person to stand in as guests during rehearsals, they wound up with me. For some three weeks, I got the raw and unfiltered version of what the human race is receiving from Brand, now on his "Messiah Complex" tour, with more calculated reflection. Even more important, I got in my thimbleful of quality time with the man himself. I had laughed at one joke he made at the VMAs or whatever, and I had forced into cocktail conversation more than once his deathless line from Get Him To The Greek, "Your life's to-do list must be a baffling document." But that was about as far as my knowledge of Brand, or my respect for him, extended. In person, it turned out, he was immensely pleasant and intimately, immediately human. And his efforts to warm up his crowd during rehearsals — they were roped in straight from the streets of Hollywood — were, stunningly, heartwarming. He sat on my lap in rehearsals and made fearlessly manful eye contact while chatting after the show. And then his retinue of friends and spiritual advisors arrived, and he floated away on a cloud of "insiderdom" and "privilege."

It was great! Who doesn't want that life? But I recognized, even as my celebrity-grubbing heart was aflame, that Brand's weird magic came from an inaccessible place. In his strange mixture of George Harrison, Eddie Izzard, and Pete Doherty, Brand was, and is, irreducibly, irredeemably, incontrovertibly British. And that is the key to grasping how we Americans can and cannot take him seriously as a would-be political messiah.

Brand is committed to inspiring us humans to revolution. For some, it is a message that's dead on arrival, thanks to the anarcho-Marxist flavor of his transformative call. But any idiot can see that virtually the whole organized world, from America to Britain to Britain's many calamitously betrayed former colonies, hungers for not only political reformation but for social transformation. Indeed, right in America's heartland — allegedly the most reactionary place on Earth — thousands of so-called rubes have quite recently thrown themselves into a project known to Ron Paul enthusiasts as a "love revolution." (The logo for this movement features the word LOVE emblazoned, backwards, where the second-through-fifth letters of the world "revolution" should be.)

We cautious optimists about the brotherhood of man should, however, stop right here. No matter how much we say it, the "American Revolution" was not, in the European sense, a revolution at all, but simply a rebellion, as John Locke described these sorts of insurgencies. In his Second Treatise of Government, Locke helped lay the conceptual groundwork for the American rebellion. Using language that wound up in the Declaration of Independence, Locke warned that a "long train of abuses" would provoke a people to "rebellare, that is, bring back again the state of war." Rather than a revolution in the French style — a forcible remaking of the social and political order, in accordance with abstract principles and demands — the American rebels sought simply to regain mastery of their destinies.

To this very day, calls for revolution fall on deaf American ears. Neither the Bastille nor the Beatles could inspire us to overhaul life itself. Americans get way more excited about being rebels without a cause than revolutionaries with the best of causes. Why does Marxism keep losing in America? Two words: James Dean.

Brand, like almost everyone really thrilled about revolution, has his sense of injustice fueled by a deep and pungent memory of aristocracy. Whatever the misfortune of the working poor in America, it simply has no cognate in the private or public imagination with the British class system. We Americans, like all born rebels, root our love for rebellion in our antagonism toward a single master — be it a strict father, a harsh teacher, or an imperial President. We may chafe at the hideous luxury and ineptitude of our most privileged celebs and politicians, but we don't have dreams or nightmares about "the ruling class." (That, for the record, is why resistance to presidents Obama and Bush has been so personal. It's not just racism or anti-Cowboy animus; contempt for displeasing heads of state is inherent to rebel thought.)

That's why we shouldn't expect much American response to Brand's call for a human revolution or the "Paulista" call for a love revolution. They're speaking the wrong language — which is too bad, given how strongly we crave an infusion of love and humanity into our debased political culture. What Americans want is a call to love rebellion. LOVE REBEL: Who wouldn't buy that t-shirt?

As limited as his political appeal may be, Brand is a half-messiah even for us Americans, and half a messiah is better than none. Despite our inbred disgust for mastery, we have somehow developed a super-perverted master/slave relationship with our celebrities. As has been obvious for decades, we build them up to take them down. As a British celebrity comedian unafraid to laugh about his past life as a heroin addict, Brand is perfectly positioned to help us escape our creepy addiction to the vicissitudes of power and fame. He's not the kind of celebrity we are most comfortable with, but he's not an alien, either.

That works to our advantage when considering Brand’s more spiritual riffs. "I don't go to strip clubs because I'm too good for them," he joked seriously in his Brand X warm-up act. "I don't go because I'm too bad!" That's the kind of human reality check that we can all benefit from before we even begin to assess our views on politics. And if we do, we can laugh along with him when we get down to the task of political transformation, American style.