Let’s say you’re a lawmaker talking to skeptical constituents. You’re trying to convince them of your loyalty to their concerns. You’ll vote for anything they support—no policy is too outrageous if the voters of the district want it. You’ve listened a string of examples, but you’ve said nothing to emphasize the point.

Now, if life were a mid-1990s teen sitcom, there would be a freeze frame. The camera would pull in, the background would darken, and you would give a meta-commentary on the events. “What should I say,” you’d wonder. “What can I tell them that will convince them of my utter sincerity?”

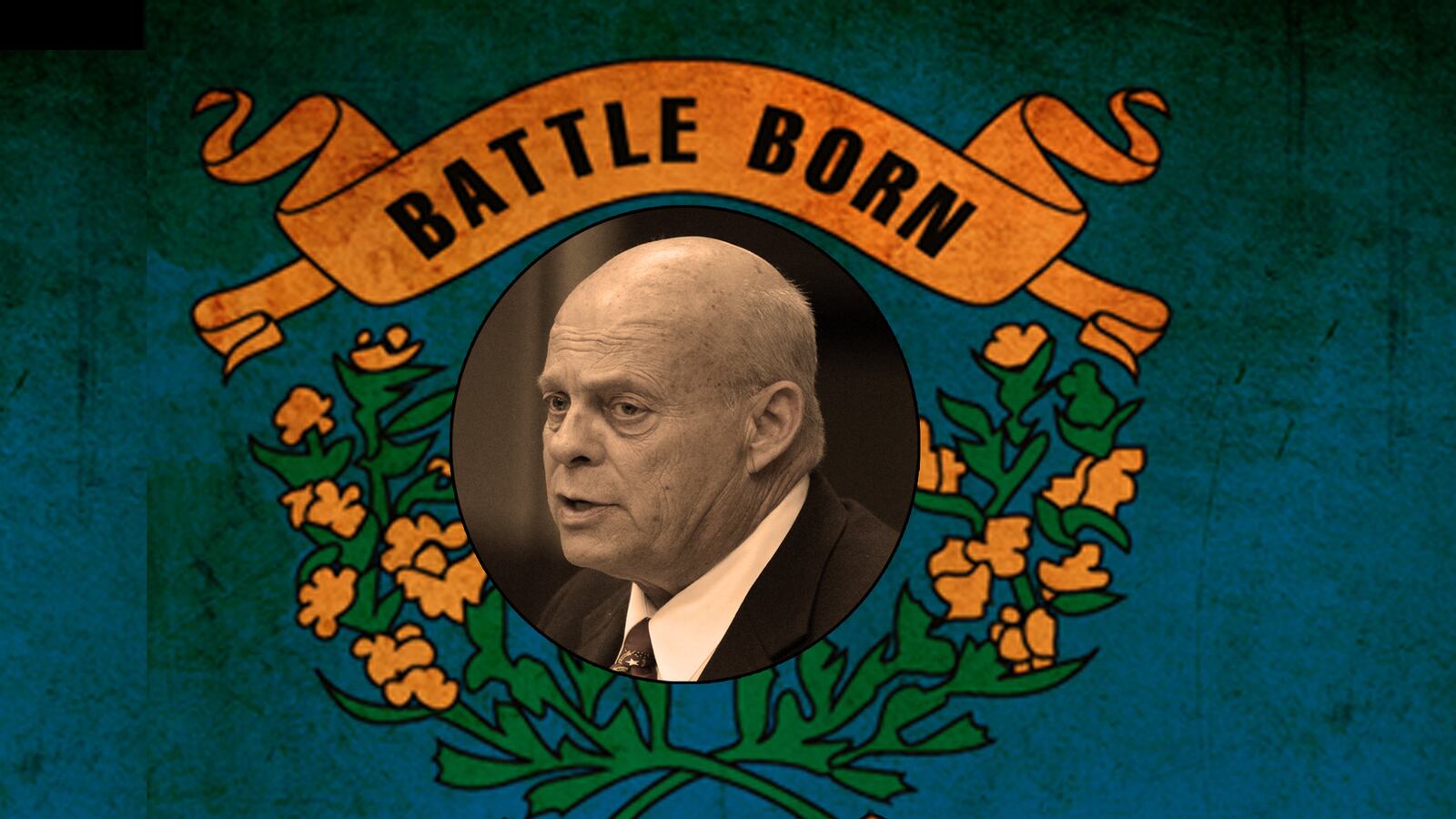

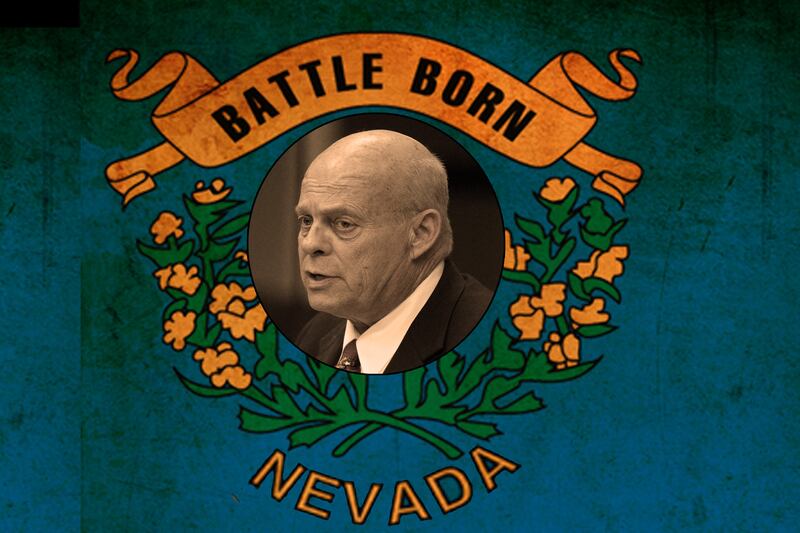

An astute politician would say something outlandish but easily dismissed by outsiders. Republican Jim Wheeler, a lawmaker in Nevada’s state Assembly, did exactly the opposite:

“If that’s what they wanted, I’d have to hold my nose, I’d have to bite my tongue and they’d probably have to hold a gun to my head, but yeah, if that’s what the citizens of the, if that’s what the constituency wants that elected me, that’s what they elected me for,” Wheeler said. “That’s what a republic is about. You elected a person for your district to do your wants and wishes, not the wants and wishes of a special interest, not his own wants and wishes, yours.”

And what is the “what” here? Slavery. Wheeler told his constituents that if they wanted slavery, he would—out of duty and obligation—vote to support it. When confronted with the statement, Wheeler immediately backtracked, telling the Las Vegas Sun that he was exaggerating for dramatic effect. “I don’t care if every constituent in [Assembly] District 39 wanted slavery, I wouldn’t vote for it,” he said. “That’s ridiculous.” Still, Republican Gov. Brian Sandoval slammed the remarks in a statement: “Assemblyman Wheeler’s comments are deeply offensive, and have no place in our society.”

The wide condemnation is understandable, but it’s more than clear from the context that Wheeler was trying to underscore a point. There’s nothing in his remarks that suggests support for slavery, and my guess is that if Wheeler were faced with the question, he would use his judgment, rely on his values, and vote like a decent person.

In other words, he would act as a representative to his constituents and not as the political mouthpiece he described at the event. Indeed, the idea that an elected official should act exactly as voters demand is incompatible with the way our government works.

At all levels of government, lawmakers are pushed and pulled by a variety of political and institutional forces. It’s impossible for any elected official—even a member of a state Assembly—to synthesize the will of the voters, the problems of constituencies, and the priorities of interests into a single guiding light. Instead, they have to balance competing concerns and plot the best possible course. Let’s say the voters in Wheeler’s district wanted to raise corporate taxes to 50 percent. Would he vote in favor of that proposal? Or would he solicit input from local business interests, talk to constituents to get a better sense of what their true concerns are, and make a judgment based on what’s best for the district as a whole? If his goal is to be an effective representative, and not just a parrot for public opinion, he’ll want to do the latter.

Obviously, that isn’t the same for all elected offices. United States senators, for instance, have wide leeway for their actions. They can take the Ted Cruz approach and use their seats as a platform for rhetoric, voicing concerns and airing the frustrations of their voters. Or they can try the Ron Wyden approach and use their resources to craft policy and delve into the operation of government. Or they can do some combination of the two, with a different emphasis for different issues.

In a representative democracy of shared powers across separate institutions, lawmakers aren’t just rubberstamps for public opinion. They’re autonomous actors who shape their states and districts as much as they are shaped by them. And the United States, in particular, gives its elected officials a tremendous amount of leeway and influence, if they want it.

It’s a great privilege to represent your community as an elected official, and Wheeler has a real opportunity to do good. He should take advantage of it.