“I cannot and I will not retract anything, since it is neither safe nor right to go against conscience.”—Martin Luther at the Diet of Worms, April 18, 1521

“I had expected to vote against Senator Kennedy because of his religion. But now he can be my President, Catholic or whatever he is… He has the moral courage to stand up for what he knows is right.” —Martin Luther King Sr., from the pulpit of Atlanta’s Ebenezer Baptist Church, October 31, 1960, the day his son Martin Luther King, Jr. was released from a Georgia Prison thanks to John F. Kennedy’s intervention.

Each age in our past history has bestowed on us its own contribution, as well as its own continuing curse. This intimate combination of contribution and curse then makes up a portion of the patrimony that we receive and pass on to future generations. The men that we Americans call our Founding Fathers, for instance, gave us, enshrined in the Declaration of Independence, a new politics that would go by the name of democracy. But they also bequeathed to us a founding racism that we have found it almost impossible to jettison. The past is not past; it continues to live with us in the present.

“Nothing will come of nothing,” snapped King Lear at his one loving daughter, as if he had just been reading Aristotle. In logic, as in evolution and in all forms of development, nothing can come of nothing; rather, everything has a precedent: something that went before, something from which the phenomenon under study springs and takes its being. The one exception would seem to be the cosmos itself, which appears, whether in ancient theologies or in modern science, to emerge ex nihilo, from nothing. But everything else known to us has a cause, a trigger, a parent, a thing from which it sprang.

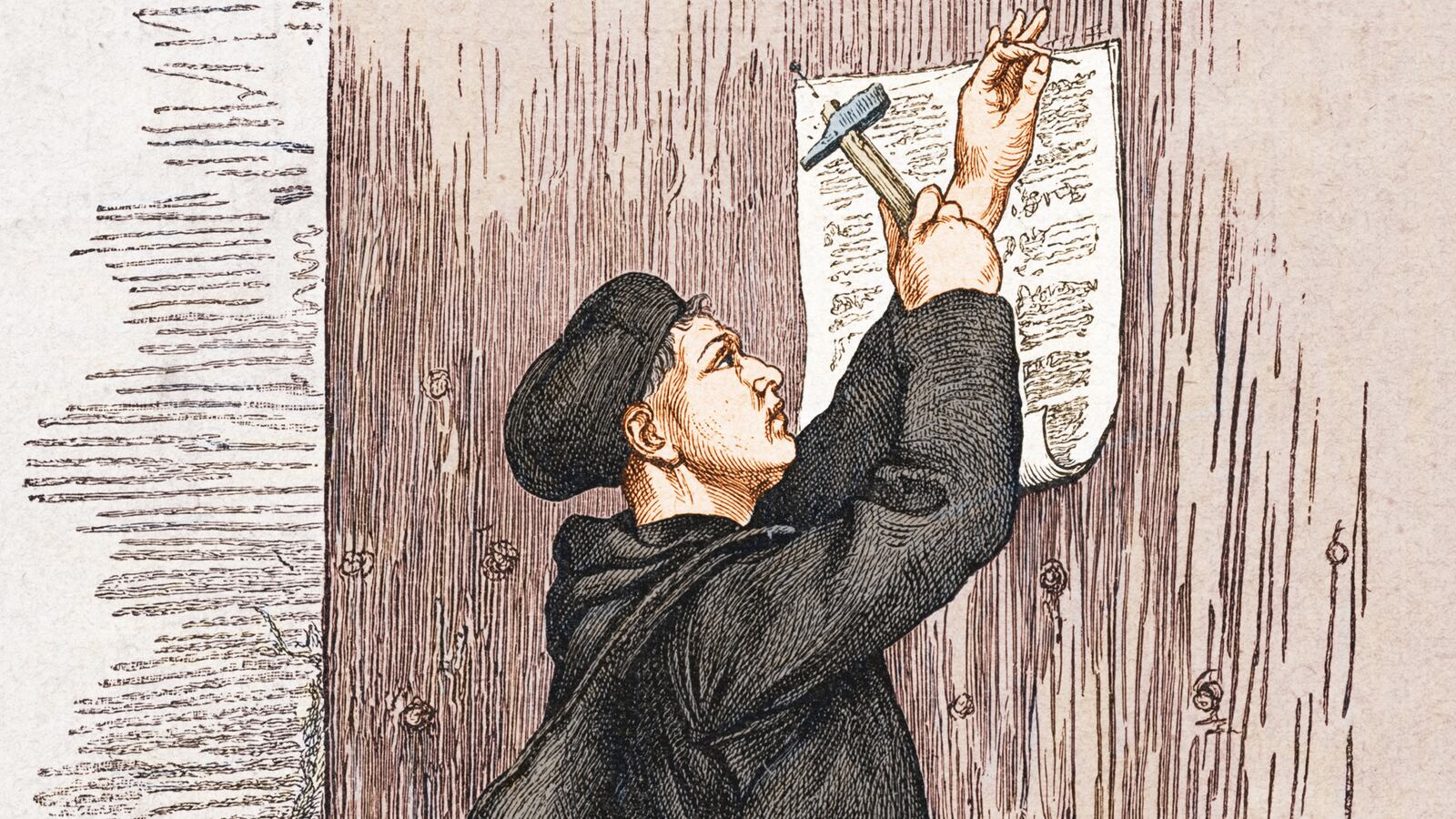

When did ego—the personal “I,” the self as we now understand it—come to be? Where do we find its earliest expression? Well, there is certainly ego in the Renaissance artists and, further back, in the self-promotion of a salesman such as Columbus. But nowhere in our earlier history does the force of ego ring so fully and defiantly as in the scene at Worms, where Brother Martin—this “pile of shit,” as he so often called himself—dared to say “No” to the assembled forces of early modern Europe, to the entire panoply of church and state, and to cite his own little conscience (surely a negligible phenomenon to the majority of his listeners) as the reason for his absolute, unnuanced, unhedged rebellion. For this reason, though we can certainly name many of his immediate predecessors, we must pause before the figure of Martin Luther and acknowledge both his astonishing contemporaneity and our, perhaps somewhat uncomfortable, brotherhood with him.

Thus, it is this scene at Worms that is memorialized in the epigraphs at the outset of this essay and at the outset of Heretics and Heroes, along with a scene from the life of Martin Luther King, Sr. Appropriately, I believe, Martin Luther’s 1521 statement about his conscience is followed by the 1960 statement of the self-named Martin Luther King, Sr. (named “Michael” by his parents), whose admiration for the original bearer of his name was lifelong. For Dr. King senior, the essence of the first Martin Luther was the man’s courage; and once he saw “the moral courage to stand up for what he knows is right” exhibited by the Roman Catholic presidential candidate he had no intention of voting for,• King switched his vote (from Nixon to Kennedy) and his lifelong political allegiance (from Republican to Democratic). King’s son, Martin Luther King, Jr., would in his brief life prove the most courageous and transformative figure of my generation of Americans, likely even of my generation of human beings.

In the end, the cultural forces that brought about such transformation need not be belittled by evidence that a heightened sense of ego may have led also to a heightened egotism. Egotism, that is, a false or disproportionate value placed on personal, subjective experience and on individual identity, has certainly accompanied a deepening of subjectivity and cheapened it throughout our contemporary world. The current inflation of ego in the self-presentation of so many public figures does not, however, erase the startling moral value of what Luther did, nor can it erase what subsequent men and women of courage have achieved in every hour since then, nor what they continue to achieve in our time.

*Martin Luther King Jr. had been arrested during a peaceful sit-in and incarcerated by the flagrantly racist state of Georgia. There was understandable anxiety that he might never be seen alive again. Senator Kennedy, beginning his run for the U.S. presidency, intervened publicly on King’s behalf, thus casting a spotlight on Georgia and forcing its minions to release their prisoner. At the time, it was a most unlikely move for a prominent white politician to make, especially toward the anti-Catholic South, at least some of whose votes Kennedy would need to win the national election.

Adapted from HERETICS AND HEROES: How Renaissance Artists and Reformation Priests Created Our World, by Thomas Cahill (October 29, 2013 from Nan A. Talese / Doubleday)