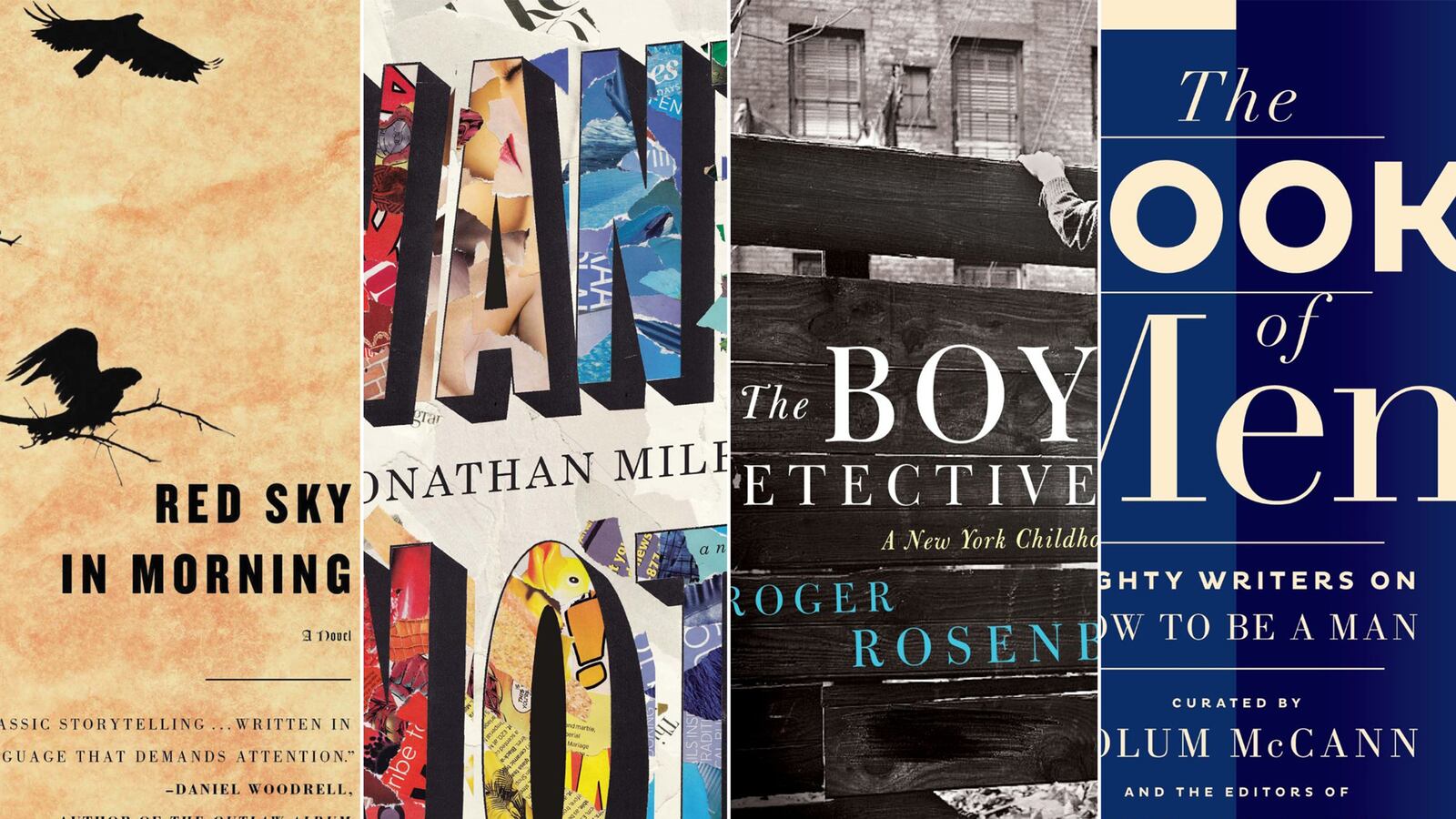

The Book of MenEdited by Colum McCann, Tyler Cabot, and Lisa Consiglio

In this collection, edited by Colum McCann and the editors of Esquire and Narrative 4, there are all kinds of men. Heroes. Cowards. Creeps. War correspondents and wanna-be lovers. Husbands and dreamers and sons. There are all kinds of women, as well. Mothers and lovers, convicts and authors. Ian McEwan, Salman Rushdie, and Khaled Hosseini are just a few of the writers who have contributed ideas about what is it means to be a man to The Book of Men; so are Edna O’Brien, Tea Obreht, Amy Bloom, and seventy-four other writers from countries around the world. That such a kaleidoscope of voices would fracture any one idea of maleness is not surprising; more startling is all the glittering shards. They are stories, ruminations, bits of wisdom, and drops of poetry, and with the exception of a few, which feel half-baked or glib, many of these pieces are marvels of precision (few exceed five pages; some are shorter than 500 words), like a story by John Boyne about a boy who tries to fly; or Mary O’Malley’s lyrical riff on the language of men versus women. If the collection lacks cohesion, or seems only vaguely interpretative, it is because the conceit is just a red herring, and everyone’s in on the jig. In his story about a dude with a vagina, Michael Cunningham casts out a line: “Men. I mean, what are we anyway?”

The Boy DetectiveBy Roger Rosenblatt

In Roger Rosenblatt’s memoir, The Boy Detective, the writer walks through New York City, down all of the streets of his past. He encounters Sherlock Holmes and Melville in Gramercy Park, where he grew up, and the sites of old crime scenes he “investigated” as a boy seeking adventure away from his all too-quiet family. As he walks, the writer “wanders, drifts, and… loses his thread.” He implicates himself in the murder of a girl that happened a century before he was born; he listens as Ulysses tells him stories of the Sirens. In a world where time does not exist, and facts intermingle with fiction, he finds he remains the detective he was. “Epicenters,” Rosenblatt writes, “are uncomfortable…If I had to choose one place to make my stand, it would not be an epicenter of anything. It would not be any place at all. That is where the best moments of our minds occur, between poetry and prose, our truest selves.” Funny, intelligent, page-turning, this memoir doesn’t just describe a 1940s childhood in New York City; rather, it ruminates on the life of an artist born in and shaped by its streets. With its noirish, casual voice, this book is also, in a way, its own kind of mystery, although, the bodies and crimes are mostly metaphorical. As the writer-detective walks, he uncovers, creates, and participates in the mysteries of his life. Or, as Rosenblatt writes, “I was the world in which I walked…Not less was I myself. I was more myself. My boy detective.”

Red Sky in MorningBy Paul Lynch

With a voice like an old Irish bard, Paul Lynch tells the story of Coll Coyle, a poor tenant farmer who, in 1832, accidentally kills his master, and is hunted by a tracker so relentless and sadistic he must leave his family and flee his country by ship and come to America, where he only finds more hardship. It is the story of two men—the accused and his pursuer—but the landscapes are so bleak, the men so violent, the children so hungry, the miles so journeying, that it reads like an epic poem about the Irish immigrant experience (the novel is partially based on historical facts). Even Lynch’s language, which is musical, close, and alive, evokes something that seems quintessentially Irish—as if you were sitting by the bard himself, in a damp, skunky pub, on a dark rainy night, as he tells you his frightening tale. “Evening was falling as the men put foot upon the bog…the two men followed Faller, who bent to the moss at intervals testing the ground for tracks seeing things the other two men could not, but they nodded to each other in recognition of the man’s abilities, supernatural they said, and kept silent behind him.” And then, “Later, when the clouds had rolled over and the darkening pallor of evening began to fall, they dragged the body out of the morass. The horse strained in its harness and the sucking pool was reluctant to give up its secret, grasping at the corpse that emerged slowing in a dripping blackness with rope looped about a lone boot.” This combination of nightmarish poetry and heart-racing plot is what makes Red Sky in Morning so compelling, like a gorgeous, terrifying ghost story. You’ll want to close your eyes and cover your ears, but find you can’t turn away.

Want NotBy Jonathan Miles

This story begins on Thanksgiving, in a world that is built upon waste. Some use the waste to survive, like Micah and Talmadge, a freegan couple, who live off the grid in Manhattan by salvaging food from trash bags. Some use the waste to make profit, like a New Jersey man named Dave, who has built his fortune off of other’s people debt—he says he has “an acquisitive mind.” For Elwin, an aging linguist in the throes of a mid-life crisis, waste—in one instance, road kill—becomes symbolic of his tepid, bloodless existence. In Want Not, Jonathan Miles’ second novel, the trajectories of these characters unfurl across and embed within more trash. “This fattening of lower Manhattan, 350 years in the making, was accomplished via landfill, the streets and buildings overlaid upon shattered remains of bombed foreign ports…upon shipwreck debris…ash, offal, horse carcasses, dung, apple cores…and other assorted garbage, piled onto the banks via shovels, pails…and dump trucks.” Eventually, this layer cake of refuse sucks everybody under, so that by the time Dave’s step-daughter gives birth to a landscaper’s baby and throws it away in a dumpster, where it is salvaged by Micah who runs to the nearest Duane Reade for diapers, bottles, and nipples, the text reads like a full-blown jeremiad. It irritates more than illuminates, partly because the characters and their motivations are all too familiar, almost typical. “Why’d you take so much?” Micah asks one of her dumpster-diving friends, who scored a load of meat too big for any of them to finish. His answer doesn’t satisfy. “Why had he taken so much?” she wonders. “Because he could, that’s why.”