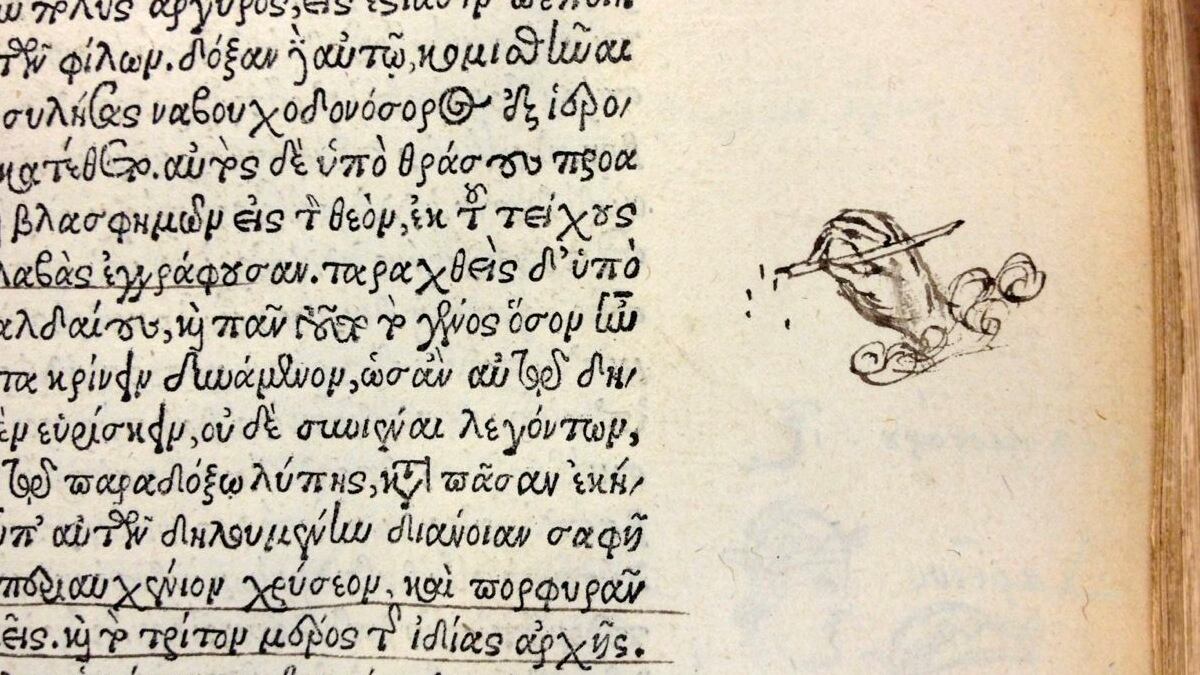

This image is of the margin of a book printed (in ancient Greek) in 1544, and then annotated within a decade or two by the English scholar and statesman Sir Thomas Smith. It was shown at a wonderful lecture given last night at the headquarters of Cabinet magazine in Brooklyn. Sina Najafi, Cabinet’s founder, got pioneering scholars William Sherman and Anthony Grafton to talk about how and when they’d come to realize that we were lacking a history of precisely how printed books first came to be used – and abused, especially, given all the scribbling that scholars did in their margins. Never again will I take reading for granted; Sherman and Grafton made clear that bookishness is a behavior worth looking into.

Sherman gave an especially lovely and lively account of the “manicule”, a little pointing hand that scholars drew, sometimes in time-wasting detail, to point from a book’s margin to a passage in the text that they cared about.

My own guess is that, once books began to be mechanically produced by a printer, the manual act of writing came to be the special sign and property of the scholar – the manicule hand thus standing, synechdochally (sorry, I’ve been among bookworms) for the wise and elevated and unmechanical reader who draws it. The manicule also points back, nostalgically, to a time in the middle ages when the scribe writing a text and the scholar annotating it might be the same person, or at very least were using the same biological equipment in producing and then using a book. Later, in a world where the hand of the scribe had been sidelined by the printer’s press, the manicule represents the return of the repressed.

The peculiar manicule in today’s Daily Pic makes all this even clearer. The hand isn’t shown simply pointing; it is shown in the act of writing or drawing, as though it were depicting itself as it annotates – you could say that it’s a manicule that talks about, or points to, or even represents, the culture of manicularism! (Today, Grafton told me that Smith himself never dripped ink when he used a pen, so his manicule’s blots are there just to make what it’s doing seem inkier, more clearly messy and manual.)

Even that isn’t the end of the matter, given the passage that’s being maniculed: the text is Flavius Josephus’s first-century “Jewish Antiquities”, and Smith’s drawn (and drawing) hand is drawing (sorry) our attention to the lines that describe Belshazzar’s famous and blashphemous feast, and especially the moment when the Hand of God appears and (literally) puts the Writing on the Wall. (Although – and it took Sherman to point this out to me – no one at Belshazzar’s meal can decipher it.) As Smith reads this mechanically printed page, pen at the ready, his hand draws the image of a writing hand to point to a text about the divine effect of writing.

As Freud might have said, if he’d had Smith on the couch: I think now we are getting somewhere …

(And tomorrow, a Daily Pic that's less like a tome.)

For a full visual survey of past Daily Pics visit blakegopnik.com/archive.