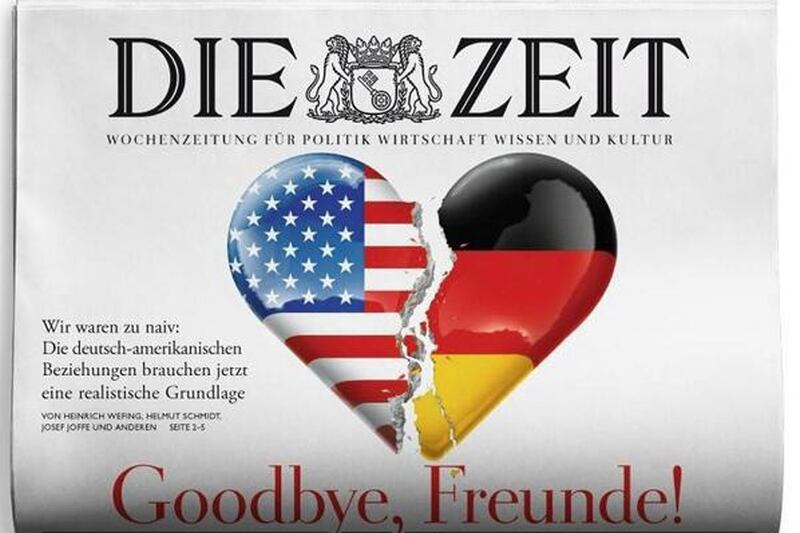

BERLIN—The cover of this week’s Die Zeit, Germany’s leading newspaper, says it all: “Goodbye, Friends.”

Illustrated by a broken heart half-painted with the German flag and the other with the American one, the image speaks to the widespread feelings of betrayal many Germans have expressed towards the United States in the wake of revelations made by former National Security Agency contractor Edward Snowden about American spying operations abroad.

Never mind that the claim causing so much outrage—that the United States was sweeping up the personal data of tens of millions of European citizens—proved false. In reality, the records analyzed by the NSA were supplied to them by European intelligence agencies, and were collected in war zones and other locales abroad, not in Europe.

But the correction to that grossly inaccurate portrayal of the NSA was lost amidst a further, more embarrassing revelation: that the NSA had been tapping the phone of Angela Merkel, the popular German Chancellor and one of America’s strongest allies in Europe. Merkel, who has tried to downplay the initial revelations about the NSA given her own pro-American proclivities, had little choice but to voice displeasure, at least for the sake of appeasing domestic anger. In an unprecedented move for a postwar German leader, she summoned the American ambassador to her office for a dressing down.

While much of the reporting about the NSA has been sensationalistic, the spying on Merkel was a phone tap too far, as the president himself acknowledged in his apology to her and his (less convincing) admission that he was unaware of its ever happening. But the German response is growing into a dangerous overreaction, one that threatens to fundamentally weaken the transatlantic relationship that has bound Washington and Berlin together for the past seven decades.

Last week, Snowden held a three-hour meeting in Moscow with Hans-Christian Ströbele, a far-left Green Party member of the German Bundestag and the longest serving member of the governmental body that oversees Germany’s intelligence services. In the 1970’s, Ströbele served as a defense attorney for members of the Red Army Faction (also known as the Baader-Meinhof Gang), the Marxist-Leninist terrorist group that set off bombs and perpetrated a series of spectacular murders throughout West Germany during the height of the Cold War. Few were surprised when, after the fall of the Berlin Wall and German reunification, it was revealed that the RAF was provided with financial and logistical support from the Stasi, the fearsome East German secret police.

Ströbele returned from Moscow a conquering hero, demanding that the German government invite Snowden to testify publically about America’s intelligence operations. But doing so will be difficult. Washington has issued an international arrest warrant for Snowden, which Germany would likely be bound to honor due to its extradition treaty with the U.S. Moreover, Germany previously denied an asylum claim from Snowden when he was stranded last summer in a Moscow airport. Asked about the possibility of offering his asylum, Merkel’s spokesman appeared to rule it out, answering that “The trans-Atlantic alliance remains of paramount importance. There is hardly a country that has profited as much from this partnership and friendship as Germany.”

But an increasing number of Germans—not just those on the far left—have joined in demanding that their government provide Snowden with safe passage. “Asylum for Snowden!” declares the cover of this week’s Der Spiegel, the country’s most prominent news magazine, which features more than 50 prominent Germans voicing their support for Snowden. The former General Secretary of Merkel’s ruling Christian Democratic Union wrote that, “Snowden has done the western world a great service. It is now up to us to help him.” “We were too naïve,” Die Zeit says. “German-American relations have to be put on a realistic footing now.”

The paper should at least be given credit for recognizing the naiveté of most Germans when it comes to the harsh reality of international affairs. For the hue and cry over American espionage illustrates just how out of touch many Germans are about the world, and their country’s place in it.

Since the end of World War II, Germans have absconded from the very idea of power politics. In an extreme reaction to their own violent history, most Germans believe that in a world where the harsher tools of statecraft—which include espionage and military force—need never be used. In 2002, Social Democratic Chancellor Gerhard Schroeder broke an unspoken rule in German politics when he campaigned on an explicitly anti-American platform, taking advantage of his constituents’ opposition to the impending war in Iraq (while in office, Schroeder labeled Russian President Vladimir Putin an “impeccable democrat” and in retirement has worked as a highly-paid consultant for Gazprom, the Russian state oil company). More recently, Germany broke with America and its European NATO allies when it refused to cooperate in the military operation against Muammar Gadhafi in Libya. It also snubbed France in its mission to rescue the African nation of Mali from an Islamist takeover. After Syrian President Bashar al-Assad used chemical weapons against his own people, the parliament of the country that forever proclaims “Never Again” didn’t even hold a debate about what sort of response the dictator’s use of genocidal weapons ought to entail. “Pacifism, sometimes in a self-righteous manner, has become part of the German DNA,” Jochen Bittner, an editor of Die Zeit, wrote earlier this week in The New York Times.

It’s not just pacifism that seems to be a part of the German DNA, but also confusion about the country’s true friends and adversaries. Despite occasional disagreements, America has long been Germany’s most important ally. The two countries share important values, namely, a commitment to human rights, individual freedoms, and maintenance of a liberal international order. As angry as most Germans may be over the tapping of their chancellor’s phone, it’s hard to see how it justifies stalling the Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership, a major free-trade agreement which some high-ranking German politicians have threatened to shelve in order to punish Washington.

Moreover, by granting Snowden asylum, Germany would be playing right into the hands of Vladimir Putin. Whatever his initial motivations might have been in exposing American intelligence practices, Snowden has essentially become an instrument in the Russian President’s plan to weaken the transatlantic relationship and divide the West. Ströbele would never have been able to score his meeting without Putin’s permission; indeed, there is nothing more that Putin could want than for Germany to welcome Snowden with open arms, thus allowing the former NSA contractor to denounce the imperialist Americans from the capital of an allied nation. "After analyzing the course of the visit, German security experts came to the conclusion that the FSB completely organized and monitored Ströbele’s visit to Moscow and effectively used it for its purposes," the German daily Die Welt reported. "The goal of the visit had been to rekindle the debate about the NSA spying affair, thus burdening relations between Germany and the United States even more."

Labeling Snowden a “whistleblower,” as most Germans consider him to be, obscures the fact that he evaded all legal avenues for releasing the information he deemed it so necessary for the public to know, instead choosing to reveal publically the highly sensitive, not to mention legal, methods by which the United States gathers intelligence. This has led to the embarrassment of his country and moralizing lectures from Europeans who ought to know better, all to the unending delight of the West’s true adversaries like Russia and China. “We would have seen him and we would have looked at that information,” said Democratic Chairwoman of the Senate Intelligence Committee Dianne Feinstein, who has herself labeled Snowden’s actions “treason.” “That didn’t happen, and now he’s done this enormous disservice to our country.” For Germany to grant Snowden asylum today would be a perverse echo of communist East Germany’s welcoming American defectors during the Cold War.

Contrast Germans’ reaction to the NSA revelations with the Russian, husband-and-wife team sent to jail last summer for spying on Germany for some two decades. Or their reaction to the revelations published last week by a leading Italian newspaper that Russia spied on delegations attending September’s G-20 summit in St. Petersburg. The German media and politicians have largely been silent, preferring to save their magazine covers and denunciatory speeches for tirades about America’s arrogance and betrayal. Meanwhile, a poll conducted last summer of German business managers, IT and security professionals found that they consider the US to be nearly as much of a threat in terms of industrial espionage as China, with twice as many considering the US to be a greater threat than Russia. This is in spite of the fact that Snowden produced no evidence of the US spying on behalf of American companies, while Chinese and Russian industrial espionage is notorious.

Perhaps this double standard is attributable to the fact that Germans hold America in higher regard; they expect the Russians, and not their purported friends in Washington, to spy on them. But it should hardly come as a surprise to the Germans that even allies spy on each other—it’s to what ends such intelligence gathering is used that is more significant. Given the all-too-cozy relationship between German businesses and Iran, Washington has reason to keep an eye on Berlin. Moreover, self-righteous attacks on America are hardly a new thing in Germany, which has long had a complicated relationship with the United States. It is one marked by love and resentment. There exists a well of gratitude for America’s rebuilding and defense of the country after World War II, but that indebtedness bred a frustration with America’s global hegemony and more militaristic approach. Former French Foreign Minister Bernard Kouchner got to the heart of the matter when he described the European anger over American spying as motivated mainly by hypocrisy and envy. “Everyone is listening to everyone else. But we don’t have the same means as the U.S., which makes us jealous.”

Germans have a right to be angry over America’s tapping their chancellor’s phone, but they also need to be realistic and put the brouhaha into perspective. Welcoming Snowden, whose revelations have done great damage to America and its allies and delighted authoritarians the world over, would risk a rupture in transatlantic relations more severe than anything caused by American spy methods. It would also adversely affect Germany’s own internal security, which is heavily dependent upon the help it gets from the NSA and other American intelligence agencies. “Without information from the Americans, there would have been successful terrorist attacks in Germany in the past years,” one German intelligence official said. Once they cool down from their outrage, Germans need to ask themselves if granting asylum to an American traitor and pawn of Vladimir Putin is really worth the trouble.