Gore Vidal opened his second memoir, Point to Point Navigation, published in 2006, writing that he hoped he was moving graciously “toward the door marked Exit… For the young, death is supremely unnatural. For the old, it is so natural that it is not worth thinking about.” Death was “unavoidable,” Vidal said of his partner Howard Austen’s death in 2003. “One or the other is going to die, it’s inevitable that both will be dead. I’m stoic.”

But there was very little calm or graceful about Vidal's final decade, as I learnt researching my book In Bed With Gore Vidal: Hustlers, Hollywood and the Private World of an American Master. They were years marked by a descent into extreme alcoholism and dementia, and by painful feuding with close family and friends. He died in July 2012 in a bed in his Hollywood Hills living room, overlooking his garden.

Late in his life, Vidal told his friend Susan Sarandon that “everyone was dying,” that “he was the only one left, he and Joanne [Woodward, another close friend]. He told me, ‘I think about death all the time. Who would have thought I’d be the last one standing?’ But he never seemed morose. He was befuddled sometimes, but on certain subjects—and if he had to give a speech—he was as clear as a bell.”

Sarandon says Austen’s death affected Vidal profoundly. “It was such a huge thing that opened up in Gore when Howard passed. He expressed to me that he missed him, and he talked of his own final days. He had never talked about it before, or shown me this emotional vulnerability." Arlyne Reingold, Austen’s sister, sat with Vidal as tears rolled down his cheeks. They would speak every couple of weeks, him telling her “I miss him, I miss Howard.” “He lost half of himself after Howard died,” says Burr Steers, his nephew. The Vanity Fair writer and film director Matt Tyrnauer, Vidal's close friend thinks it “very unlikely that he told Howard he loved him. Sadly it’s inconceivable.”

In these later years, growing more isolated and unhappy, Vidal employed handsome male assistants, like Muzius Gordon Dietzmann and Fabian Bouthillette. “He surrounded himself with young men: typically straight, handsome and strong. There was no sexual element at all,” says Jay Parini, his longtime friend and former literary executor.

“Muzius was very splendid, a first class guy, very, very heterosexual,” says Parini. “He’s married with children now.”

Bouthillette had been a twenty-eight-year-old lieutenant in the Navy and part of the protest organization Iraq Veterans Against the War when he met Vidal in November 2008. “His public persona was snobby and ‘aristocrat-y’ and he liked fights, but to me he was one of the kindest people I have ever known. He really took me under his wing.”

Was there a sexual dynamic between Vidal and Bouthillette? “It wasn’t anything overt,” insists Bouthillette. “Yes, I was an attractive guy and he responded to that. He wanted someone with competence to take care of him and with the social grace to look good while doing it, and I guess I had that. He was in a wheelchair and needed someone to be with him wherever he went. I could do the job of personal assistant and wheelchair-pusher and look good doing it. Of course he appreciated that: Gore always got what he wanted.”

After Austen’s death Vidal still used hustlers, just as both men had done throughout their relationship. His one-time pimp and trick, and longtime friend Scotty Bowers, says: “He was in a wheelchair and not really able to move. Sometimes there would be guys there, in their thirties and handsome, he had met. Nothing happened. He thought he wanted someone in bed, but Gore just wanted company. We’d talk, have four, five, six drinks and soon Gore would fall asleep. In the last couple of years he was not in the position to have sex.”

Vidal could still charm and humor. The painter Juan Bastos recalls his 2006 visit to Vidal's home with great affection. “I was supposed to be there for ten minutes, to take some pictures for preparation to do a portrait for the Gay and Lesbian Review. It was three in the afternoon and he said, ‘What would you like to drink? Gin, whisky, vodka?’ I said a glass of water would be fine.”

On the table was a picture of Jacqueline Kennedy with a dedication to Vidal, says Bastos. “It read something like, ‘Gore, it’s impossible to keep this serious when one is with you, Jackie.’” Vidal said the picture had been in a drawer for years: “I don’t like the woman, but Howard did. Howard said, ‘Let’s frame Jackie,’ so we did. He’s no longer with us, so the picture is there because it reminds me of him. I still don’t like the woman.” Vidal told Bastos: “When Onassis died, he left Jackie twenty eight million dollars and the yacht. Jackie grabbed the check before the ink was dry.”

There was also a picture of Vidal, featuring a male model coming out of his swimming pool, with Vidal and his sour expression looking out at the viewer. Vidal told Bastos he had shown the picture to a straight friend who said the model had the best ass he had ever seen, which, said Vidal, showed that even straight men will appreciate a beautiful ass. “He liked Southern men, he told me that Southern men were the best in bed,” says Bastos. “One day he was watching television and the person was saying ‘Today in North Carolina…,’ and Gore said, ‘Beautiful boys in North Carolina, working class kids, very nice. South Carolina’s pretty good too.’”

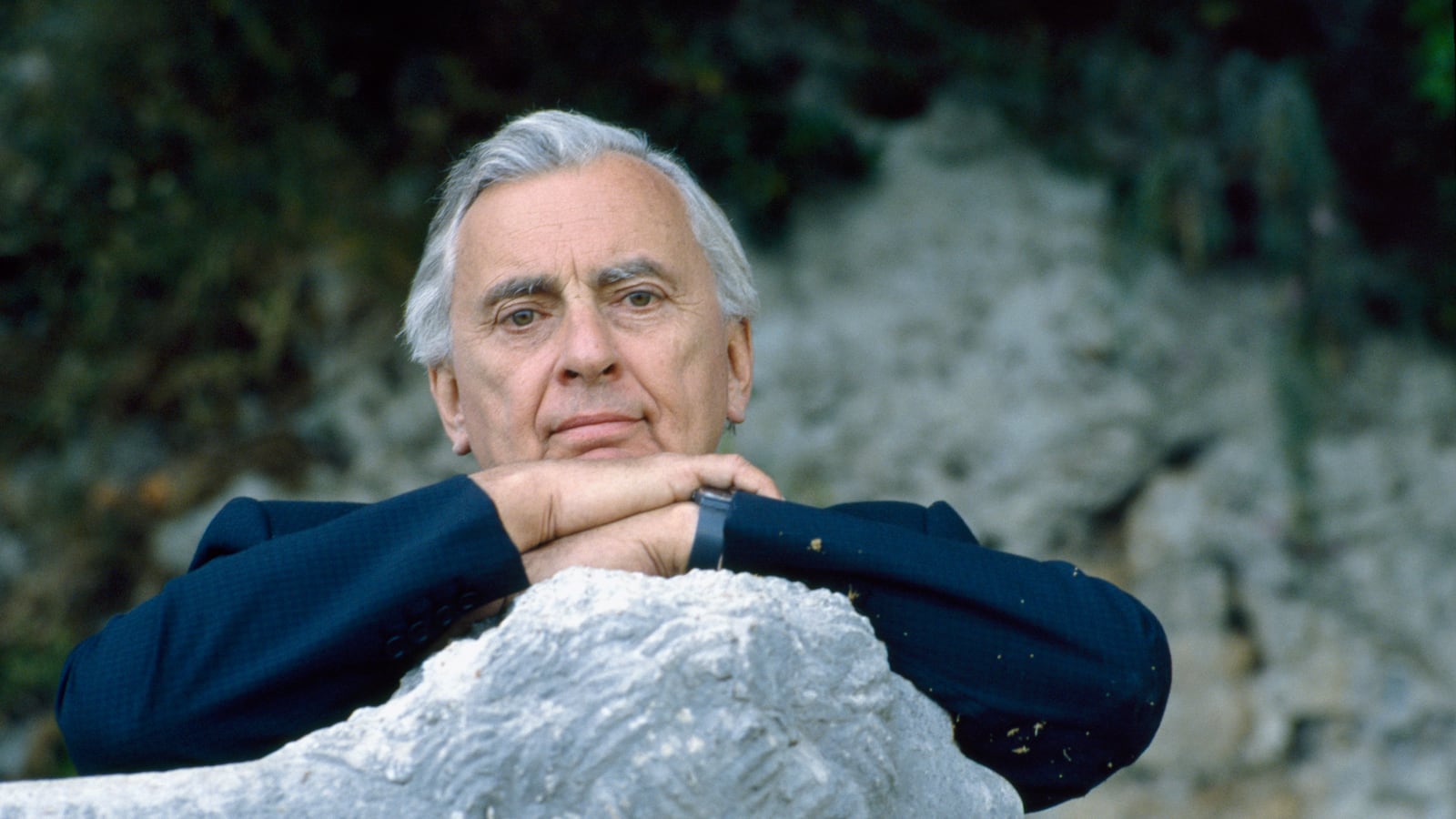

Bastos took some pictures of Vidal indoors and in the garden. I said, “Gore, you have such a great face.” He held his cheekbones and said: “It’s all here. If you don’t have these, just forget it.” There was a “big ego and vanity to him” and he “still saw himself as a sexual being,” says Bastos. “When he saw my pastel portrait, he said, ‘I didn’t know I had these jowls.’ ‘Let me soften them up,’ I said. ‘I never thought I looked like my father—my father looked like a fox,’ said Gore. I took a finished, enlarged portrait to him in a beautiful frame as a present. He showed it to Norberto [Nierras, Vidal’s majordomo] and said, ‘Put this picture next to my father, so there will be two foxes on the table.’”

Vidal was always kind and generous to Norberto Nierras, his devoted personal chef and houseman for the last eleven years of his life. "After Mr. Austen passed away he didn’t eat so much," says Nierras. “I don’t feel like eating, Norberto,” Vidal would say. This saddened Nierras. “From then on I made small portions and soups, like Hungarian goulash, and the bowl was always finished. He would sit at the table by himself and sometimes say, ‘Sit down, Norberto, have some wine. You’ve been tiring yourself on your feet in the kitchen.’ It delighted me, I was an employee…being a Filipino liked by Mr. Vidal, that is something.” Nurses were hired to tend to him, but late at night if Vidal needed anything he would call for Nierras. “He asked me to play the music of Mr. Austen. He cried when he talked about him. I never heard him say ‘I love, or loved, him’ but he said he missed him.”

Depression consumed Vidal in these final years say his friends: about the state of America, how he had been "erased" from the cultural landscape, and about losing Austen. He feuded with friends. Jay Parini, Vidal's friend and former literary executor, thinks that “early on” Vidal “put on this Gore Vidal mask, this supercilious grandee, and it kind of stuck. It was super-glued on. He was suffering in it, it didn’t have much air in it. He was the loneliest man I’ve ever met in my life. Without Howard he would have had nothing.”

Professionally, Vidal's last decade while not fallow was not golden. He feuded with the novelist Edmund White in 2006, who he accused of "vulgar fag-ism" after White wrote a play, Terre Haute, imagining a sexual connection between a Vidal-type figure and a Timothy McVeigh-like figure (Vidal was a McVeigh supporter and the pair had corresponded.) The night of Barack Obama's historic Presidential win, Vidal appeared on the BBC, slurring and insulting the host, a far cry from his earlier grand, commanding primetime performances. In 2009 he published a series of photographs with captions from his life, Snapshots in History's Glare. The same year, when I interviewed him for the Times (London), he said he was proudest of not killing anybody, despite being very tempted. America, he added, was "rotting away." He had switched his allegiance from Obama to Hillary Clinton after Obama's win and, during our interview, even imagined Obama being assassinated.

“He died horribly,” says Bouthillette of Vidal. “He was definitely drinking too much, especially for an elderly diabetic. He was lonely. The last ten years bought the worst out in him. He just lost it. Many days I felt like saying ‘Gore, go fuck yourself,’ but knew he was a sad, lonely man and you could see the true spirit of him. In public he played the tough guy, but he was a very good listener if you had something of use to say.”

This is an especially fulsome tribute, as Vidal claimed Dietzmann and Bouthillette had “kidnapped” him in France on another trip there in 2010. They had not, but it was a sign, for Burr Steers, of how quickly Vidal’s mental deterioration was progressing: “The paranoia and drinking were becoming incredible.”

Patty Dryden “could see the writing on the wall” for her friendship with Vidal. “Muzius is a dear person, and no one was closer to Gore or could do more for him. So when Gore accused him and Fabi of kidnapping him I stood my ground, asking what on earth he was talking about, which he didn’t like. The alcohol got too much and ravaged his beautiful mind.” Dryden asked why they would want to kidnap him. “Money,” Vidal told her. She told him he was being ridiculous. "I saw him two weeks before he died. He was physically there but not there. I held his hand. I focused on the good, but was still angry with him."

When Vidal's half-sister Nina Straight saw him in the spring of 2011, “after he had gotten home from that farce in which he claimed he had been kidnapped,” Vidal “ranted and raved about everybody who had, in fact, helped him. It was absurd and I just let Gore have it. ‘You’re drunken, out of your mind, none of these people are liars,’ I told him. We really went at it hammer and tongs. He just kept repeating himself: that he had been betrayed and that everyone was against him. I kept grabbing his nose and pulling it, calling him Pinocchio. The third time I did that he grabbed my wrist and left a great black mark on it. I told him to get real. As I left he said, ‘You’re worse than your mother.’”

In the spring of 2012, Burr Steers says, “when the doctors finally did a brain scan, they found so little left they couldn’t believe it was still functioning. It was horrible. It was exactly what happened with my grandmother, his mother. She, like Gore, had dementia and ‘wet brain.’” The proper name for the syndrome is Wernicke-Korsakoff, a brain syndrome suffered by long-term alcoholics characterized by a number of symptoms, including confusion and hallucinations. When Vidal and Steers had taken Austen’s ashes to be interred, Vidal had said “that he really didn’t want that kind of long, drawn-out thing to happen to him, and yet it happened and in the worst way,” says Steers. “It was a really horrible final act.”

Nina Straight says her half-brother was “a physical coward but not scared of death.” At his bedside she told him, “I’m here, I love you,” focusing on the “wonderful” things he had done for her, like encourage her writing.

“I saw Gore in the hospital, then at home,” recalls Tyrnauer. “He had pneumonia and couldn’t speak very well. He held my hand, which was very atypical, squeezed it. He said something I couldn’t hear that sounded sarcastic, which was reassuring. I think I told him I loved him, which he wouldn’t have liked. I didn’t get an ‘I love you’ in return. But everything is relative. A faint squeeze of the hand was more than sufficient.” Steers recalls that, "In the last couple of months he was gone. The only thing he reacted to was pain. The doctors said it was as strong as an ox, considering he was so sedentary. Pain was the only thing that brought him around.”

Just as Vidal planned, his ashes are interred at his joint plot with Austen’s at Rock Creek Cemetery in Washington, equidistant between the final resting places of Jimmie Trimble, Vidal’s enduring love-object from prep school, and Henry Adams, the writer and grandson and great-grandson of presidents. For the first nine days after his death Nierras lit a candle next to a picture of Vidal.

Was he happy, I asked Vidal when I interviewed him for The Times of London in 2009. “What a question,” he sighed, then smiled mischievously. “I’ll respond with a quote from Aeschylus: ‘Call no man happy till he is dead.’” If that leaves Vidal in too warm and cuddly a resting place, imagine instead the icy contrarian who, upon alighting from a cab in New York with his friend Diana Phipps Sternberg responded to the cab driver’s entreaty to “Have a nice day,” with: “No thank you, I’ve made other plans.”