M.I.A. predicted the NSA scandal. Back when critics, fans, and detractors were busy lampooning her for her preference of French fries (truffle, in case you missed the Lynn Hirschberg/New York Times firestorm), the Sri Lankan-British artist was making unfounded but astute observations about the nature of government electronic surveillance. In 2010’s “The Message,” the first track on her widely panned /\/\ /\ Y /\ album, she warned us plainly: “Headbone connects to the headphones / Headphones connect to the iPhone/ iPhone connected to the Internet / Connected to the Google / Connected to the government.” And in the album’s accompanying visuals and promo cycle press, she stuck with that contention.

Yet, by her own admission, it fell flat. “I’d learned the language myself, I built the platform myself, got to a microphone myself…Then I told the story—and it didn’t translate. A lot of people were like, ‘Just make music; don’t talk about politics,’” M.I.A. explained in an interview with NPR this week.

It was yet another instance of Mathangi “Maya” Arulpragasam spouting a steadfast but disappointingly nebulous political conviction, and was received largely as either paranoia or self-aggrandizement. Her account of the Sri Lankan civil war had been met with similar reactions. When she first broke out with 2005’s Arular and later followed it up with the smash hit Kala in 2007, M.I.A. proudly touted her father’s membership in Sri Lanka’s separatist Tamil Tigers and integrated the group’s symbols into her work. When it turned out that Arul Pragasam had, in fact, been a founder of the less violent, but equally active, Eelam Revolutionary Organisation of Students, the inconsistency of her story and the vagueness of her views, although ultimately inconsequential, ended up being used as a giant strike with which to discredit her.

The frequent frailty of her arguments about issues that are otherwise pointedly relevant—racism, immigration, war culture, and the military industrial complex—came to be what M.I.A. was known for and did the twin job of winning her the public’s favor and turning us against her.

Accordingly, it’s fairly easy, and indeed tempting, to write M.I.A. off as a faux-radical who relies on the borrowed aesthetics of revolution to sell records. But that superficial reading belies her truest political work: her commitment to self and the exploration of identity in a world and industry that is more comfortable with easily digestible predetermined narratives, particularly when it comes to racialized people.

In a 2005 interview, comedian Margaret Cho, who is of Korean descent, described the nature of her own work as being inherently political: “It’s political because I don’t have a choice—the nature of my existence is political.” Despite the particulars of their different personal histories, the statement also rings true for M.I.A. (and for other artists for whom mere existence is an act of defiance).

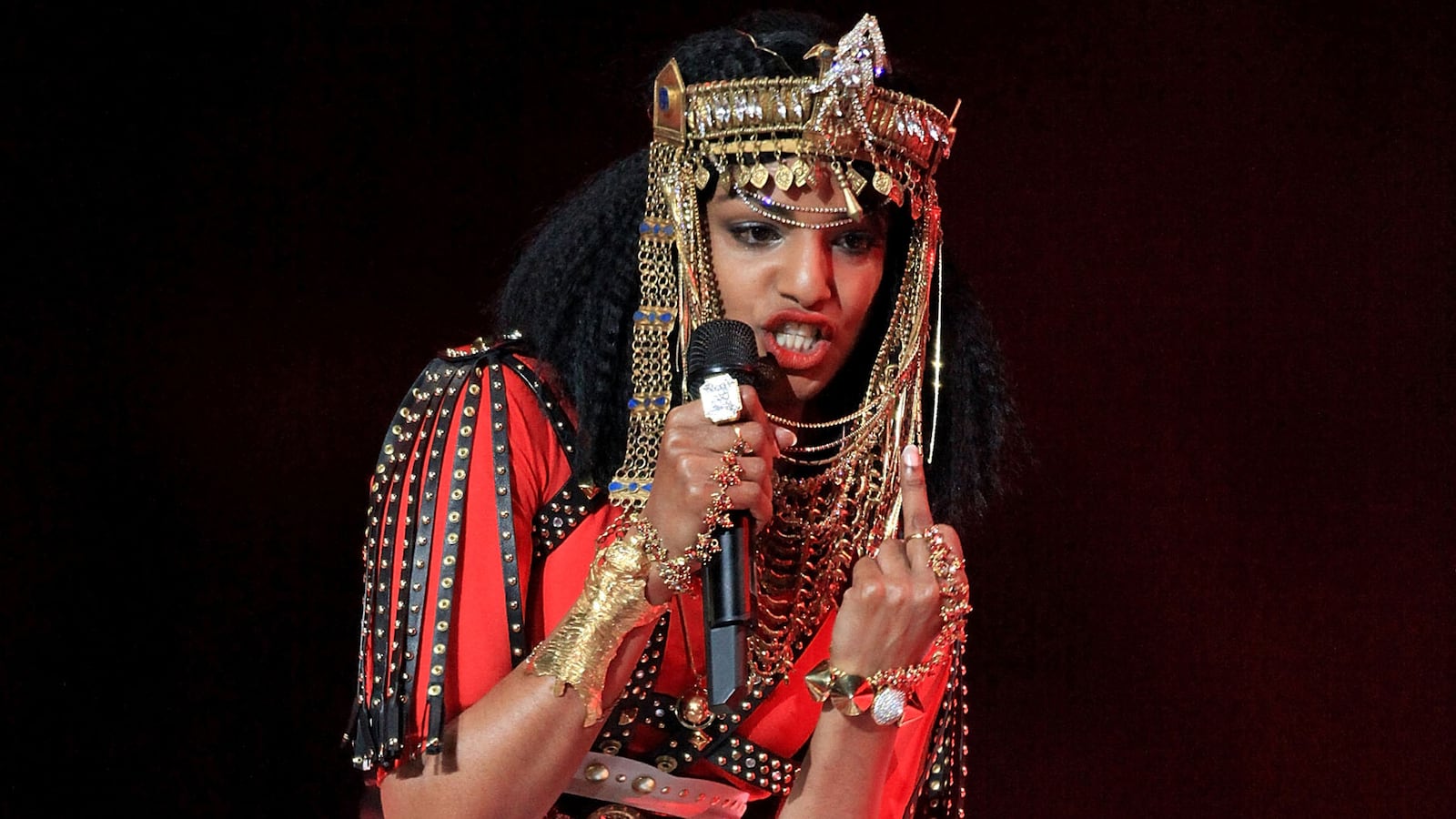

M.I.A.’s latest album Matangi—titled in honor of her namesake, the Hindu goddess of music and learning—plays like a conceptual middle finger, a defiantly personal reclamation of the brown girl narrative that was wrested away from her. It’s largely a success that sees her at her strongest and most convincing: the most polished raw edge, a very human superhuman.

The outmoded belief that one can either be a rebel or a pop star, and that both are inherently at odds with each other, is the very status quo that has continuously been foisted onto M.I.A. It’s also the status quo that she actively redefines on Matangi, by encapsulating the complexities and wide-ranging possibilities of identity. On the album, and throughout her career, she evokes multiple, seemingly contradictory but ultimately reconcilable modes of being.

By gelling Kollywood samples with hip hop and R&B and Brazilian Carioca funk and Angolan kuduro and UK Bass, she reconciles the possibilities of being both Sri Lankan and British, revolutionary and mainstream, flawed and aspirational, of intently wanting to effect change and desiring nice things. It is a synthesis that embodies the unfortunate but unassailable reality that having the courage to be oneself and assert one’s identity in the face of a society that constantly demands the opposite is a political action.

M.I.A.’s aesthetic commentaries on racial, cultural, and religious identity, immigration, and globalism have, in retrospect, been more impactful than her overt politics. More than her words, it is the sounds she makes and the textures she creates that frame her work as a uniquely hegemony-defying proposition, the likes of which has hardly ever existed on such a large scale. That she—brown, immigrant, woman whose work deals primarily with being brown, an immigrant, and a woman—is a pop star and not a fringe artist is itself the ultimate subversion.

“Boom Skit,” one of Matangi’s Hit-Boy-produced gems, sees MIA verbalizing the message sent to her by America: “Brown Girl Brown Girl / Turn your shit down / You know America / Don’t wanna hear your sound / Boom Boom jungle music / Go back to India / With your crazy shit,” she spits in a tone that is as comedic as it is searing.

In response to that sentiment, and more broadly to anti-South Asian racism and the infuriatingly analogous co-option of Hindu culture by the white yoga industrial complex, she asserts her own version of Hinduism, of brownness, and, in essence, of herself. She combines markers of religion, culture, and spirituality with an indelibly global, futuristic outlook that bends to no one’s whims but her own. And that is more rebellious than a hand full of middle fingers at the Super Bowl could ever be.