From a cocktail party came a village.

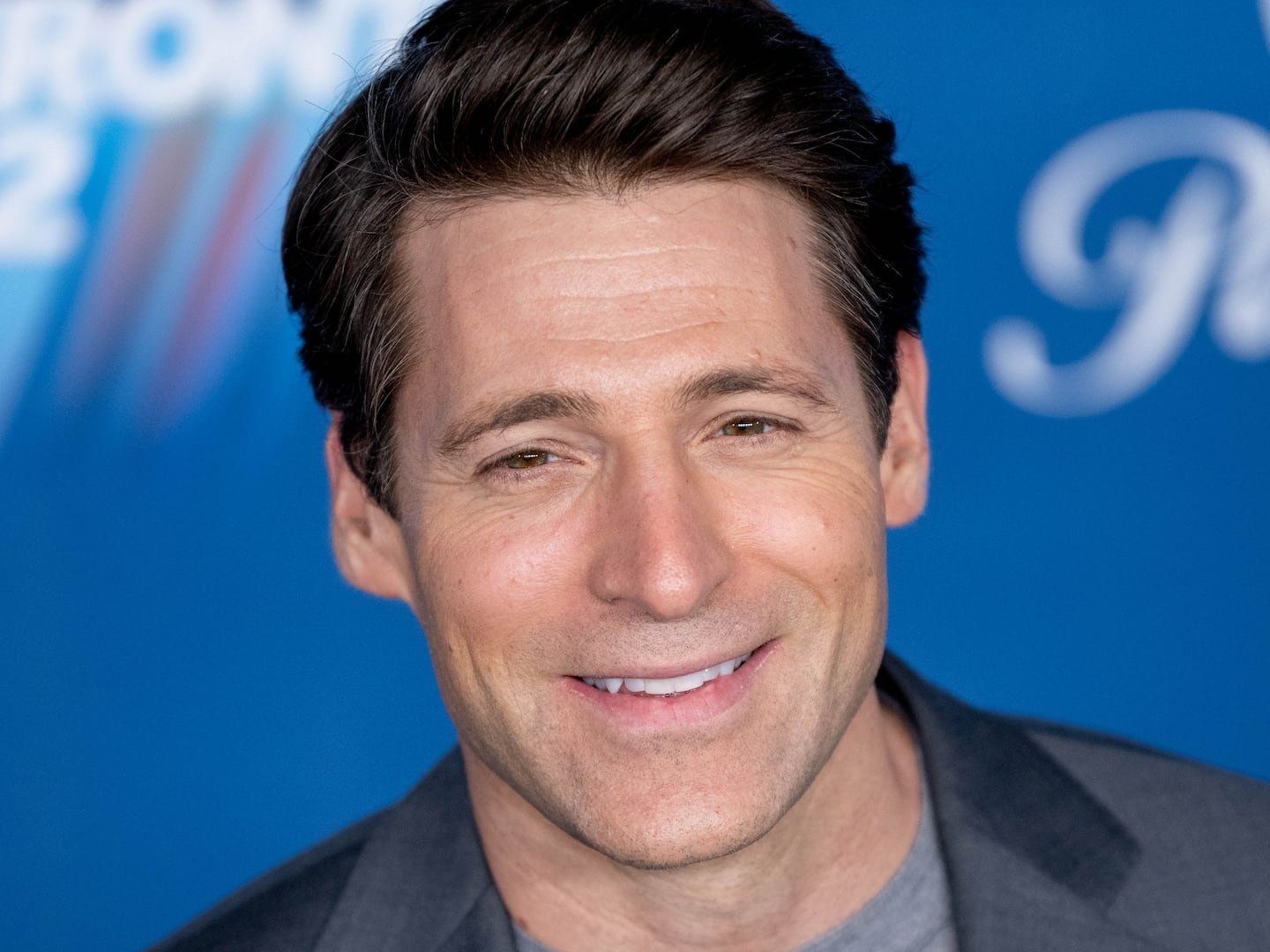

Veteran development worker and Columbia professor Josh Ruxin’s life-changing voyage began when one of those too-good-to-pass-up offers presented itself at a rooftop gathering in New York City. A donor and admirer of his entrepreneurial company, Health Builders, offered him the funds to build a real-life prototype of a perfectly developed sustainable village. It was in the fledgling days of the Millennium Villages project—a collaboration between the United Nations and Columbia University’s Earth Institute—and though no village was yet slated to take root in Rwanda, it was ideal ground to break. It didn’t take Ruxin long to pick up his life, fiancée in tow, and move to the war-torn nation still suffering from its genocidal wounds.

In A Thousand Hills to Heaven, released last week, Ruxin spins through the trials of rebuilding a village from the ashes, then constructing a restaurant from scratch—and, during it all, beginning his own family.

The book prefaces with a pledge that the story’s focus will not be historical or political—but it’s virtually impossible to ignore the brutal 100 days of killing that Rwanda suffered nearly two decades ago, and much of the tale is devoted to horrific stories of killing, survival, and, finally, reconciliation.

Ruxin calls the genocide “a shadow over everything, but a fading shadow,” though he doesn’t skirt the horrifying details as they come, which is often enough. They take the form of bones dug out of his new backyard to the incredible stories of loss and survival told by his workers and colleagues. The tales of machete-wielding militias, daring escapes, and heroic rescue efforts don’t sting any less than when we first heard them in the late '90s, and they’re brought to life in Ruxin’s book through a fascinating array of characters.

In the years since the genocide, Rwanda has become a model of government-mandated sustainable practices in the aid world. It is a country that wisely refuses to be a landfill for cast-off vanity work thrown its way, and its thoroughly vets foreign projects to ensure that they don't just put a bandaid over major development issues.

As such, it proved the perfect testing ground for Ruxin to make his case that entrepreneurship and private sector are the paths to bringing long-term prosperity to Rwanda, helping it to wean itself off the unstable reliance on handouts that has so often eroded other development hotspots in Africa and elsewhere. “Why, after all the fundraising and new charities and billions in foreign aid from successful countries and full-hearted volunteers heading off to all corners of the world and donated goats and sponsored children, is there still so damn much poverty in the world?” Ruxin poignantly wonders at one point.

The book is named for, and at times centers around Heaven, a restaurant begun by Ruxin and his wife, though it doesn’t actually enter into the story until halfway in. First, Ruxin works his way—a bit sluggishly at times—though the first five years in the country, as he attempts to turnaround a destitute community.

He and his team are assigned Mayange, a desperately malnourished and decrepit town, lacking paved roads, electricity, and any semblance of proper health care. The 25,000-person cluster of five villages was known as “Rwanda’s Warsaw Ghetto.” Spoiler alert: Ruxin's plans, for the most part, work spectacularly well. Within two to three years, Mayange's health centers are clean, well-staffed, and running so smoothly a local women in charge of funerals jokingly complains she’s been put out of business. Farmers are trained and supplied with disease-resistant crops. Exports boom. Residents enjoy electricity and health care and smooth roads. The example is now being scaled to all 30 districts of Rwanda.

Though Ruxin's writing can be repetitive, his most original thinking shows through in arguments about the purpose of aid, the best practices for transforming communities, and the ethos that leaders and workers must struggle together in the field, not engage in brief drop-by visits to the poorer places on Earth. The biggest need, he says, is for the aid community to set in place a mechanism that’s self-sustaining enough to live on long past the departure of foreign donors. “When foreigners stay too long they become a reason for people to doubt their own abilities,” he writes.

Even those disinterested in the wonk of development work will be enchanted by the characters in A Thousand Hills to Heaven, from the ambitious young workers serving at Heaven to pay their way through school, to the family’s driver, nicknamed Op-Ed, who has an arsenal of traditional proverbs for every situation. Lesson learned: never turn down an offer at a cocktail party. Ruxin and his family haven't been able to tear themselves away from Rwanda, and they still dine at Heaven, where, he writes, “there is a very good evening view of the end of poverty.” It's a good incentive to stick around.