Warhol's "Silver Car Crash" sold for $104.5 million last night at Sotheby's in New York, which was either too little, or too much. Too little, because the night before, a much less important picture by Francis Bacon sold for $142.4 million at Christie's, breaking every record for an artwork at auction. It might have been nice if, for once, there were some correlation between such a record and the historical importance of the work that set it – as would have been the case with the "Car Crash". Last night's $104.5 million was too much, by exactly $4.5 million, because at an even $100 million, Warhol's picture would have matched the fake $100 million price tag that Damien Hirst, a Warhol devotee, attached to his diamond-studded skull in 2007. Hirst created a work, and a social "performance", of sorts, that was all about how art and artists enter the marketplace, but Warhol had staked out that territory 45 years before, in even more subtle and complex ways. It started in 1962, with the Campbell's soup can as iconic commodity, then within a year Warhol had expanded the idea to cover the commodity status of celebrities – Marilyn and Jackie and Liz (so famous that their first names are still enough to call them to mind) and soon Andy himself and the Superstars he created from scratch. And then Warhol's notion spread further, to cover even the calamities served up to us over and over again in tabloids and on the news – poisoned cans of tuna, suicide leaps and fatal car crashes. (The celebrities Warhol chose and created were also all calamities, of a sort, since even Liz had just survived a calamitous illness when Warhol pictured her and had starred on screen as a car-crash victim, and of course Warhol and his Superstars were models of broken lives.)

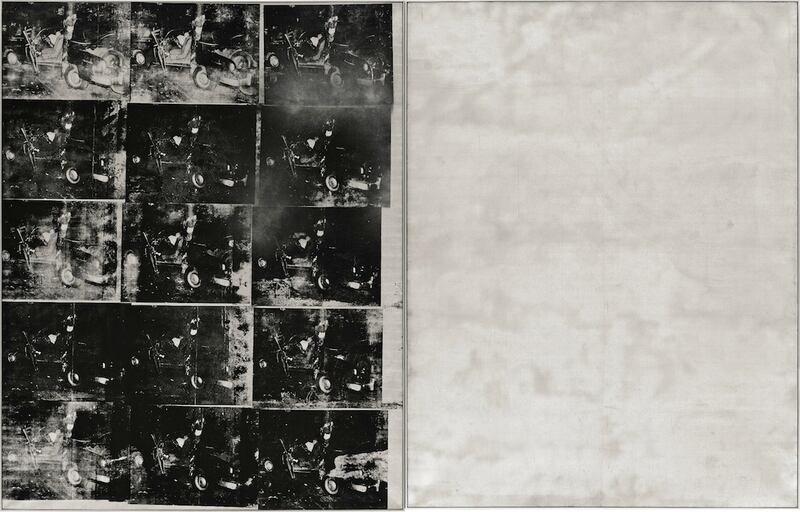

Warhol silkscreened his "Crash" in several "colorways" (he borrowed the concept from fabric and housewares marketing) but this silver version is best of all, because the shiny paint itself stands for the bullion that's at the symbolic heart of every transaction in a commodity culture. It's presented .999 "pure" in the work's right panel, and then on the left with a black image of disaster that reads as a tarnish on its surface. (This is just about the moment when Ralph Nader was starting to rouse the nation's consumers against the hazards built into the cars they were buying – although I note that this wasn't a movement against consumption itself, but in favor of a safer, purer form of it.)

So Warhol's Pop art – a misnomer if ever there was one – isn't a cheery celebration of Pop-ing commodity culture, though that's how it was often billed (sometimes by Warhol himself). And it's not a preachy, political attack on that culture, which was another common reading. It's a full-bodied portrait of commodification, with its lights and darks left intact and in play against each other, and in which we see ourselves. (The blank right-hand panel could be mirror as well as bullion.)

That portrait saw a kind of apotheosis last night, in an auction that declared and celebrated the greatness of this work of art but that also laid bare a culture of consumption that, more than ever, has escaped the bounds of reason. Warhol saw consumption as a force for democratization in an America where, he wrote, "the richest consumers buy essentially the same things as the poorest.... A Coke is a Coke and no amount of money can get you a better Coke." . But last night at Sotheby's, we saw consumption's new, darker side, as our insane economic divide (read this terrifying report) made itself clearer than ever and infected even a great work of art. After all, one way or another, every dollar of the record millions that got spent at Sotheby's was a dollar not paid out to the poor suckers making our cars and feeding on Campbell's soup – when they can afford even that.

Warhol's "Crash" may have started out depicting hoarded bullion, but last night that's what it became.

For a full visual survey of past Daily Pics visit blakegopnik.com/archive.