Though many are mourning the untimely death of Ace Hotel chain founder Alex Calderwood last week at age 47, two interior designers are suffering his passing as a nearly familial loss.

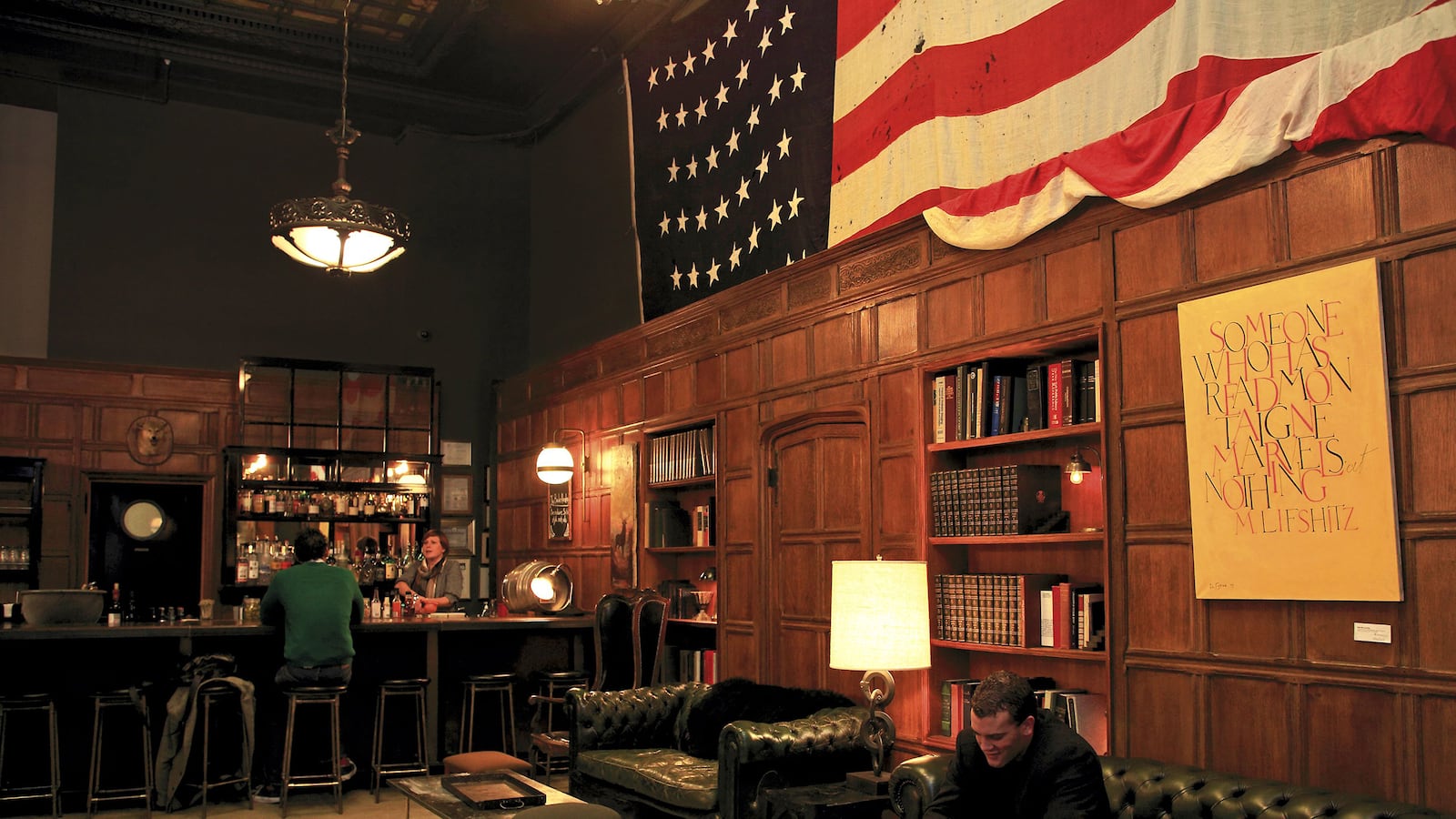

The pair—Robin Standefer, 49, and Stephen Alesch, 48, principals of the New York City-based design firm Roman and Williams—collaborated with Calderwood to create the much buzzed about Ace Hotel New York that opened in 2009, crystallizing vintage-cozy design trends that were emerging on the west coast and in Brooklyn. Plaid-clad 20-somethings flocked to the Ace’s dark, pubby lobby and its wood-paneled restaurant, the Breslin, with its snout-to-tail menu. It was just the right level of egalitarian comfort and locavorism that a post-crash populace needed.

“We were like family,” Standefer said of the designers’ three-and-a-half year working relationship with Calderwood. “We found comfort together creatively and had a lot of common values—imperfection, experience, the story. Like a band, we played better together. Stephen and I are married, so we have a close companion to make things with. Alex was like that.”

The trio haunted east coast flea markets, sourcing knickknacks that would adorn the lobby and guest rooms. On a rainy day at the Brimfield, Massachusetts, antiques fair in 2007, they discovered the massive American flag that hangs above the lobby bar.

“I remember Alex and I holding it up,” Standefer recalls. “Stephen came over and we asked, ‘Do you think it will fit?’” Much of the rest of the distressed-looking lobby furniture, including the metal coffee tables and grommet-punctured leather sofas, were custom made for the space.

Standefer and Alesch, who worked as Hollywood art directors and set designers before opening a New York shop in 2002, are known for their offhandedly gothic, yet chic, efforts in domestic interiors and restaurants. In the past few years, the pair completed Facebook’s Menlo Park, California, cafeteria and HuffPost Live’s New York studio, along with several hotels. They are currently at work on a hotel project in Chicago, a restaurant in Istanbul, and the renovation of a San Antonio brewery, among other projects.

Standefer and Alesch’s knack for creating convincing atmospheres helped them recast a down-at-the-heels SRO hotel in midtown south into the Ace. Removing a century’s worth of carpeting, drywall, and alterations, they transformed the SRO into a 272-room boutique destination, a process that was part rescue, part reconstruction. Enter the hotel now and it’s hard to tell which details are new and which ones came with the place. That said, if there’s an exposed filament bulb—the oft-derided gesture of the aesthetic they’re associated with, even if there aren’t very many at the Ace—it’s definitely new.

But what exactly made the Ace such a sensation with the twenty-somethings that arrived once its doors opened?

“Those kids grew up with zero history,” Alesch says. “They were born in apartments, condos, shopping malls. They were driving around in Camrys. There’s no history there. Modernism was pushed so hard on them that when they hit their 20s, they decided to rebel against the aesthetics of their childhood.” And so they embraced the Ace.

No doubt the Roman and Williams-Calderwood look will itself enter the history books. They’ve created the dominant design trend of our times, just as hotelier Ian Schrager and his partner, the designer Philippe Starck, came to define sleek 1990s hospitality. But where Schrager and Starck pared down, Calderwood and his team gussied up. Calderwood’s first two Ace hotels, in Seattle and Portland, might best be described as dumpster-dive chic. In New York, the atmosphere is more sophisticated, something like a hunting lodge crossed with an apothecary shop and an old-time public library. It’s a nostalgic look, though Standefer and Alesch reject that label.

“We’re tying together threads of time,” Standefer says. “We have reverence for history but also for modernity. We realized, perhaps five or seven years ago, that you don’t have to abandon history. And Alex was interested in rescuing things, not just discarding everything. He didn’t like planned obsolescence.”

“Sometimes those trapping of modernity – the space-age, modern lobby – come from not being modern,” Alesch adds. “Our philosophy has always been touch it, use it, destroy it.”

Indeed, in the public imagination, Modernist architecture became synonymous with corporate vulturism—even though the movement’s founders had entirely more utopian ideals. Calderwood and his acolytes were about humanizing big business.

“We really mourn him,” Standefer says. “I don’t think there is anybody we collaborated with as fluidly as we did with Alex.”

At the time of Calderwood’s death, Standefer and Alesch were embarking on another hotel project with Calderwood, in a city the designers won’t name.

“We still might do it,” Alesch said. “We just don’t know yet.”