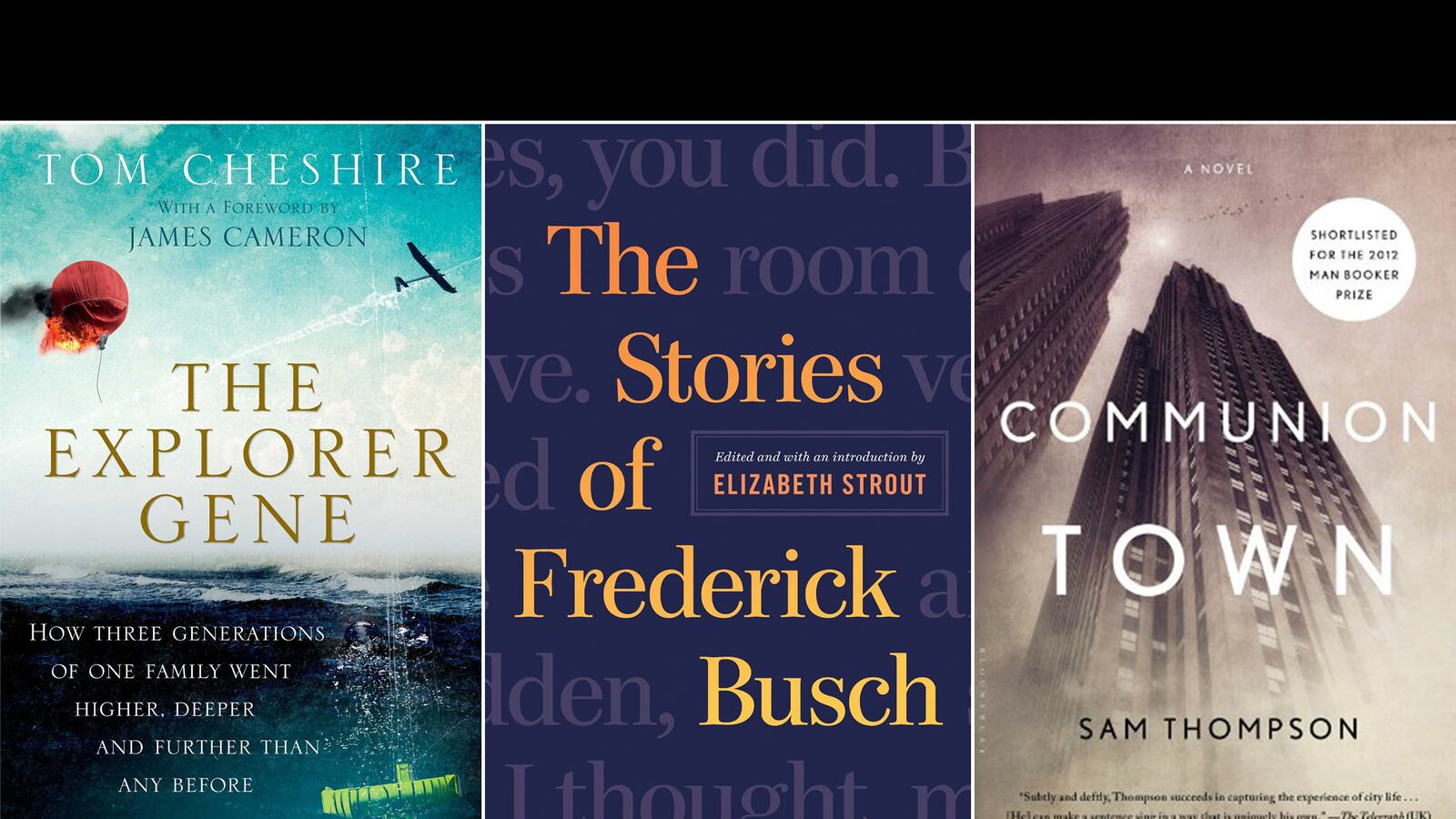

The Stories of Frederick Buschby Elizabeth Strout

When he died of a heart attack in New York in 2006, obituaries of Frederick Busch called him a “writer’s writer,”—someone who “seemed to impress critics more than the mass audience,” as The New York Times put it. It’s a shame his work didn’t reach a broader audience in his lifetime. A new collection of Busch’s stories reveals a powerful writer whose fiction is as deeply compassionate and accessible as it is well-crafted.

These stories find ordinary American husbands, wives, lovers, parents, siblings, and children in crisis. Sometimes, the source of the cataclysm is plainly identifiable—as in “Ralph the Duck,” in which a campus security guard rushes to save a suicidal student, “somebody’s red-headed daughter, standing in a quadrangle how many miles from home and weeping.” Elsewhere, the cloud that looms is something more subtle. That’s the case with “What You Might As Well Call Love,” a story about young parents unspeakably frightened by the weight of adult responsibility.

Pleasingly, Busch’s women are just as brave and perceptive as the strong but frequently faltering men they love. So are his children. His books may have never seen major sales, but when it comes to crafting “good language: words that are useful to someone other than me,” (as he put it in one interview) Busch is wildly successful. “These are stories for grown-ups,” editor Elizabeth Stout writes in her introduction to the volume. And yet, as in stories for children, Busch often reserves a final parting wisdom—or twist of the knife—for his tales’ last lines. Though his characters may be broken, Busch’s clarity of vision and purpose never are.

—Mythili Rao

The Explorer Geneby Tom Cheshire

In 1931, Swiss scientist Auguste Piccard became the first human to enter the stratosphere. “The beauty of the sky is the most poignant we have seen,” he wrote in his logbook upon ascending 10 miles above the earth. Piccard, an eccentric, absent-minded and indisputably brilliant scientist, was eager to take advantage of his location to conduct a series of experiments on gamma rays. But soon before he could get to work, he lost control of the balloon he had designed and built himself. As the balloon drifted over the mountains, headlines predicted Piccard’s certain death. Ultimately he survived—chastened less by his close encounter with death than by his brush with sensational journalism.

In The Explorer Gene, science writer Tom Cheshire presents a fascinating cross-section of Piccard family history. Auguste’s curiosity and trail-blazing inclinations hardly made him unique in his family. Previous Piccards included Rodolphe, the inventor of an exploding cannon ball; Paul, the inventor of a salt-making thermocompressor; and Auguste’s father, Jules, who installed the first telephone in Switzerland. Similarly, Auguste’s son, Jacques, and grandson, Bertrand, too, were driven to explore the far reaches of the earth—Jacques deep under the sea, and Bertrand, as the first man to circumnavigate the world in a balloon.

Tracing multiple generations of the eccentric and ever-brilliant Piccard clan, Cheshire, an editor for Wired in the UK, explores the desire to explore that so deeply drove these men. In the mid ‘90s, researchers linked a certain gene sequence with a “novelty seeking” personality. Do the Piccards possess this gene? Cheshire is less interested in the literal, chromosomal answer than the figurative one. As Explorer Gene makes clear, whether inherited or learned, a taste for the exhilaration of discovery is a hard thing to shake.

—M.R.

Raw: A Love Storyby Mark Haskell Smith

Mark Haskell Smith’s latest one-word titled novel (following Moist, Delicious, Salty, and Baked) is Raw: A Love Story. Raw, however, shares with these previous books more than just titular brevity; Smith remains a gifted satirist with a comic touch that can be either howlingly broad or devastatingly precise. With Raw, Smith takes aim at reality TV. Sepp Gregory, a mostly harmless set of abs made famous on a Real World clone called Sex Crib, publishes a book that, inexplicably, is good. Literary blogger Harriet Post takes notice, and immediately attempts to track down his clearly very talented ghostwriter. This unlikely pair fall into bed together, run afoul of the law, and go on the run—and then Raw gets really outrageous. Though consistently surprising, fast-paced and nearly always funny, Raw is more than just a lively romp. Smith saves his best satire for a topic he knows all too well: the publishing industry. In Raw, the highbrow world of the literati is predatory, fickle, and constantly chasing the next big thing—and Smith skewers it with as much gleeful zeal as he attacks his much easier targets.

—Thomas Flynn

Communion Town: A Novelby Sam Thompson

When British writer Sam Thompson’s Communion Town was longlisted for the 2012 Man Booker Prize, it was subtitled A City in Ten Chapters. In December, it is being published stateside as Communion Town: A Novel. Thompson is such an experimental writer, however, that neither classification quite captures what the book actually is. Ten stories set in an unnamed city, each told in a different style, each indebted to a different form of genre fiction, Communion Town would be entirely fractured if not for crossovers between the stories that range from a shared character to a background gag. Thompson is a master of voice—there are take-offs of both Raymond Chandler and Arthur Conan Doyle—as well as imagined geography. The city itself is a wonderful creation; the recognizable echoes of existing cities like London, New York, and Tokyo combine with Thompson’s often fantastical inventions to create a setting that is both recognizably ordinary and compellingly surreal. Each of the 10 narrators reveal a new facet of the titular metropolis, from an abattoir in meatpacking district to the extensive criminal underworld. Communion Town is a book for the careful reader; the stories, though they stand on their own, build to a multi-narrative that rewards attention to detail. Thompson’s dexterity in this regard is the surest sign that he is a writer to watch, and the Booker listing a sign of things to come.

—T.F.