It’s just past the one-year anniversary when Gianfranco Soldera, a complex 76-year-old man who makes some of the most coveted Brunello di Montalcino in the world, slumbered in his Tuscan home, unaware of the carnage about to take place. It was a few weeks before Christmas but not all creatures were snug in bed. A few yards away, under protective darkness, a vandal shattered the bulletproof window of Soldera’s Case Basse winery and opened the spigots on ten botti—huge oak casks used for aging the precious liquid. In a matter of minutes, 61,000 liters of wine spanning five vintages and worth upwards of $25 million went down the winery floors’ drains. As the world woke up on December 3, 2012, so did the rumors and speculation: Mafia attack. Retribution. Disgruntled employee.

Any number of people could have committed the painful crime. “Let’s face it,” wrote Jeremy Parzen on his Italian-wine—centric blog, dobianchi.com, when the news broke, “many observers of the Italian wine world (myself included) couldn’t help but think, to borrow a phrase from Lennon, instant karma’s gonna get you.” He concisely summed up what is often unsaid about the man some have described as Montalcino’s most iconic and difficult producer.

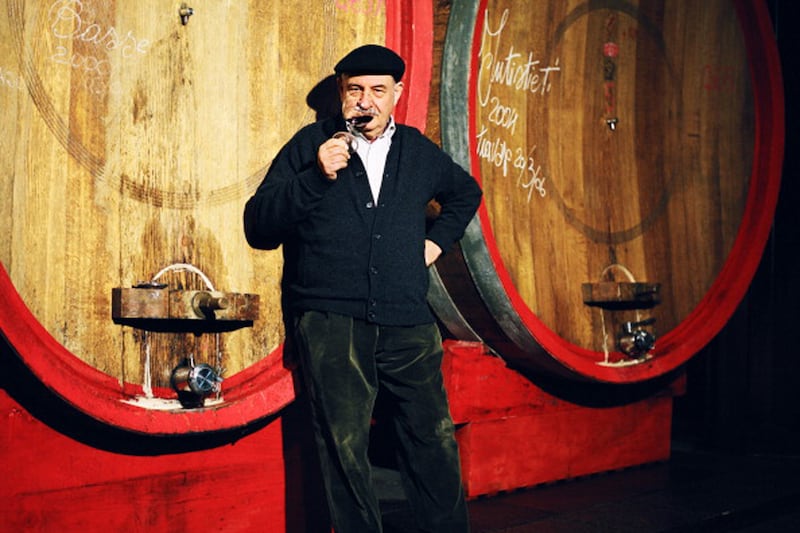

For all of his bravado, Soldera’s home at Case Basse is no palazzo, but a humble, sweet stone house at the end of a long cypress-spiked and vine-bordered road. The gentleman himself walks briskly, with a slight stoop. He had a pleasantly jowly face, punctuated by a brushy mustache under his fleshy nose, his pants always fastened to suspenders. When I paid him a visit recently, it was clear that he’d rather be having a root canal than answering questions.

He spoke no English and so his daughter Monica, who works with him—often as the kinder, gentler face of the wines—began to interpret as he recalled the moment he realized what had happened. But then, she choked up and sobbed into her fists. Her father rushed to her side. Putting his arms around her, he kept on repeating, “It is over, Monica. We have to go on. It is over. We have to go on.”

When Monica was able to continue, she explained, “My husband was early into work that morning. He found my father in the kitchen and said to him, ‘It’s all gone. There is no more wine, no more wine.’ My father didn’t think it was possibly true, and he went to the winery. From the outside he could smell the truth.”

Winemakers are notoriously openhearted to a colleague in need, and, no matter what they personally felt towards Soldera, his neighbors all shouted for justice.

Fabrizio Bindocci, the head of the Consorzio del Vino Brunello di Montalcino, had never been a Soldera supporter, but he came to pay a condolence call. Fearful that a member and one of the most lauded Brunello producers was now in ruin, the group offered to donate some of their own wine for him to sell to offset the financial loss.

As extreme and high profile as the Soldera case might have been, wine crimes appear to be on an upswing. The vines of Domaine Romanée Conti were held for a million-euro ransom on the threat of being poisoned. A storage facility holding some of the best wines of Napa was torched, in a fire that claimed 4.5 million bottles and effectively erased the histories of several notable American producers. Rudy Kurniawan, the swashbuckling Los Angeles wine collector, was arrested for extensive wine forgery in March 2012 and is still awaiting trial. Then there was a heist of 300,000 Euros worth of Selosse champagne from the grower’s own cave. With the exception of the Soldera and Napa incidents, wine crime is mostly always staked on profit, not revenge. The execution-style wine hit at Soldera’s Case Basse appeared to be something that only the Italians could think of, especially here in the hills of Montalcino, a place one local wine writer has called “a viper’s nest of vintners, where rivalries among the competing labels rule.”

Looming over it all is the memory of Brunellogate. By law, Brunello must be made from 100 percent Sangiovese Grosso grapes. But, in 2008, some producers were accused—and subsequently convicted—of blending foreign grapes into their wines, mostly to increase production. An anonymous letter had been written to the wine authorities, snitching on various esteemed Brunello producers. Some of them blamed Soldera for the tip-off. The letter’s connection to Soldera was never proven, and he’s actually not the kind of man who does anything without his name on it. Those found guilty of the wine fraud were fined, but were allowed to remain part of the Consorzio. The Brunello di Montalcino honor war was escalating. Some wondered if the hit on Case Basse was revenge for Soldera’s perceived role in blowing the whistle.

Within a few days of the attack, a former Soldera employee and Rome native named Andrea di Gisi was nabbed and brought in for a mug shot. Damning evidence began to pile up: video coverage, wiretapped conversations, a pair of wine-soaked jeans, a confession. Di Gisi, 39, had worked at Case Basse on and off for about three years. It turned out he had been fired months before for mishandling barrels—a sin that Soldera, the prickly perfectionist, could not tolerate. The sacked employee had then spent months planning the vengeful act on his ex-boss. Di Gisi was quickly convicted and given four years under house arrest. (By contrast, the arsonist behind the Napa fire was given 27 years in prison last year.)

But in Montalcino, well enough is never let alone. When I arrived for my audience with Soldera, the story had segued from Macbeth to Characters in Search of an Author.

Soldera, ever eager to rattle the local viper’s brood into a hissing fury, withdrew from the Consorzio, the very group that tried to bail him out. Soldera denounced their offer of wine as “inadmissible and offensive, a fraud to the consumers.” The group said, ‘You can’t quit, you’re fired.’ And then it sued him. Soldera did himself no public relations favors when he initially let the press assume that all vintages were lost; it later turned out that there might be as many as 5,000 bottles per vintage salvaged. Upon hearing that Soldera had saved some wine from the attack, Bindocci, the head of the consortium, commented, “It’s like the wedding of Cana,” referring to Jesus’ famed miracle turning water into wine.

Soldera continued to keep tongues wagging when he announced an astronomical price hike for his 2006 Vintage, from $300 to $600. This would keep the bottles off of many wine lists, but they would fit quite nicely into the cellars of collectors, especially those who want a trophy with a story. In another twist, he decided to label the next shipments of 2006 as an IGT (Indicazione Geografica Tipica) instead of a DOCG Brunello, a good couple of clicks down the exclusivity scale. The price hike? That’s just arithmetic. Soldera lost half the vintage so he needed to double the price. The IGT? He doesn’t need the name Brunello. People who buy his wine buy Soldera first.

Soldera comes across like that uncle who, once affronted, crosses you off forever. But there are other facets to the man, like his generosity, as demonstrated by his Soldera Award for young researchers, and his nurturing side, as he has displayed with the Padovani twins, sisters at their up and coming Campi di Fonterenza winery.

When I visited, he refused to open the doors to the winery and the scene of the crime, but instead offered a walk through his wife’s magnificent rose garden, his meticulous vineyards, his pond, “Where all life begins,” he said. He enthusiastically showed off his pruning technique for me and lunch with him was required. We drove a short ways to his favorite restaurant, Il Leccio, in Sant’angelo in Colle. In the empty trattoria, he berated the waiter for bringing the wrong decanter and wine glasses. Soldera believes in a wide-mouthed vessel, just as he believes in wide-mouthed, lead-free stemware. With the decanter and glass situations peacefully resolved, the eating and drinking commenced and the Soldera paradoxes continued. The 2000 Case Basse riserva was silky with a hint of tannin and rust—warming, sensual, layered, with a near-perfect balance and not much eccentricity.

The 1985 Rosso from his Intistieti vineyard was more quirky: difficult at first, full of wet cement and a touch of high-tone volatility. The more the wine interacted with air, the wilder and more unbridled it turned. It was as if the wine had been blessed with the power of speech.

There are many loose ends surrounding the crime and the bickering, even though somewhat abated, will undoubtedly flare again. But to me, the biggest mystery is how a man accused of being so difficult and arrogant can make a wine—yes, extravagantly priced—of such complexity and humility. Who cares if he was difficult? So was Picasso. Though Monica’s husband has been working alongside with Soldera and is prepared to carry on, Soldera is in his late seventies. Who knows how much longer these wines will be made in exactly the same way. He might be a pain in the ass, but he is a master.

As he drained the last of the ‘85 from his glass he told me he has no patience for the small-town jealousies around him. They are the past. “The future is in the youth,” he said.