“It always seems impossible until it’s done.” Nelson Mandela

Nelson Mandela’s legacy is intertwined with the notion of freedom and equality, which doesn’t seem especially connected to wine at first glance. But the South African wine industry’s recent and continuing dramatic revival is analogous to the hope and freedom Mandela helped usher into South Africa since his release from prison in 1990. It is self-indulgent but insightful to view Mandela’s contribution to South Africa and beyond through a vinous lens.

For starters, Mandela’s release and the end of apartheid precipitated an opportunity for South Africa to export products to economies like Great Britain and the United States. In a business model that would have been impossible twenty years ago, Mandela’s daughter and granddaughter are now making a line of “fair-trade” African wines available in the U.S. and other global markets. Members of Mandela's family told The Wall Street Journal this year that while he was longer drinking wine for health reasons, his favorite wines were "South African sweet wines, such as Klein Constantia’s Vin de Constance," which recently reclaimed its place among the world’s greatest, after nearly a century of dormancy.

The wine is impressive. It carries a legacy that dates back to 1685 and is one of the most storied wines in history. The estate’s Dutch founder, Simon Van der Stel, wanted to start a winery in “the most favorable area of the Western Cape.” He put men to work digging baskets of soil throughout the Cape, then sent all of the samples for testing. He preferred the decomposed granite soil in the valley facing False Bay, claimed it, and named it Constantia.

Other notable fans of the nectar included Jane Austen, who noted its “healing powers on a disappointed heart” in Sense and Sensibility, and Napoleon Bonaparte, who is said to have drunk it daily and had 30 bottles shipped to him while in exile on the island of St Helena every month. (The winery’s website suggests that Napoleon even requested a glass “on his deathbed, refusing all other food and drink.”) Russian Czars, Baudelaire (in Les Fleurs du Mal he compares Constantia wine to the sweetness of his lover’s lips), and Charles Dickens, who wrote about it in his unfinished novel The Mystery of Edwin Drood, were all devotees.

Vin de Constance is made from Muscat de Frontignan grapes (related, but not identical, to the Muscat Blanc à Petit Grains grape, which is also known as Moscato and planted throughout the globe). The original vines on the estate perished in the late 19th century from oidium and phylloxera, and Klein Constantia shut down.

Production resumed nearly a century later, when new owners dreamed of reproducing the wine and went to great lengths to locate the strains of the original vines. They managed to track down the original 1656 source grape variety, Muscat de Frontignan. In 1982 the roots of the revival were planted.

Constantia’s revival is perhaps the first success story of returning prominence and excitement to South Africa’s wine scene. When apartheid ended, countries including Great Britain and the United States ceased their anti-apartheid boycotts and the export market opened. Since then, the wine scene has gained momentum.

In the American sommelier community, until very recently, South African wines have remained largely an afterthought. Wines made of Pinotage (a hybrid grape criticized for tasting like burnt rubber) and a swath of innocuous Chenin and Sauvignon Blanc had marred South Africa’s reputation. But that perception is starting to change. Sommelier, winemaker and James-Beard Award-winning author Rajat Parr visited Swartland in April this year and was blown away by his experience. He spoke of the “Swartland Revolution,” a group of wineries that are interested in producing wines on par with any of the world’s great estates.

“Going to see the cellar of Adi Badenhorst is like going to see the cellar at [Thierry] Allemand or [August] Clape, in the Rhône Valley,” he raved, mentioning two global benchmark estates. Badenhorst’s winery is not twenty years old, yet it’s experimenting with surprisingly classic vinification techniques such as fermentation in neutral oak barrels, adding minimal sulfer dioxide during production, and fermenting Syrah whole cluster as opposed to de-stemming it.

I asked Raj what he found most compelling about his recent visit to Swartland. “It’s so exciting,” he said. “There is little talk of the past; the focus is on the present and the future. It’s unbelievable – there are no boundaries. People have the complete freedom to grow.”

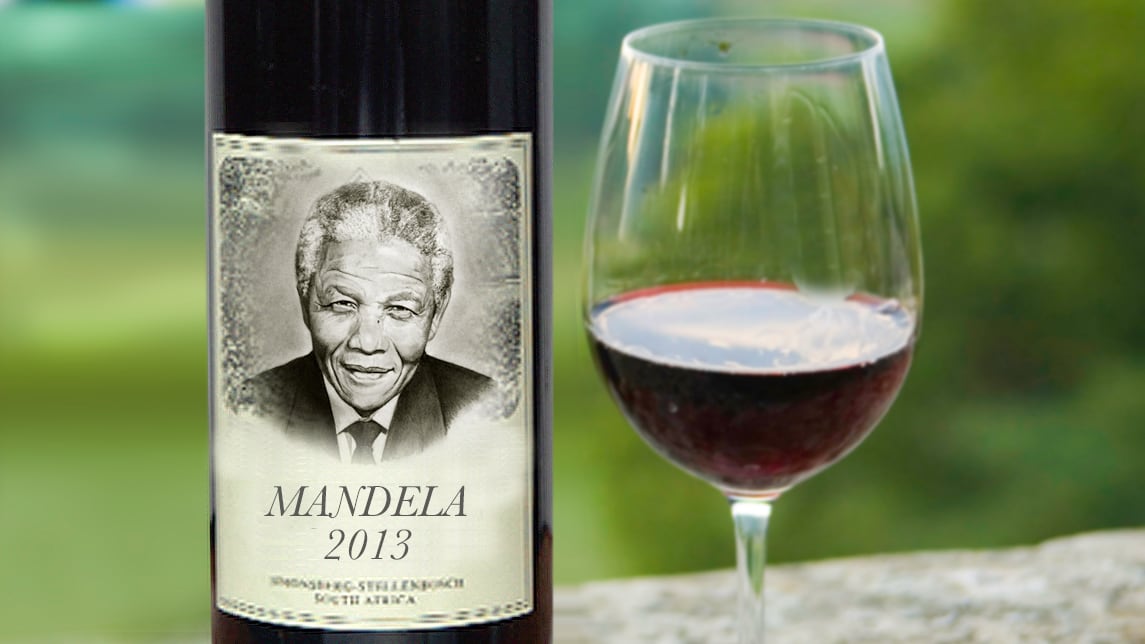

Nelson Mandela’s daughter and granddaughter’s recently launched wine brand, House of Mandela, is growing, too.

To hear that South Africa’s wine industry, non-existent a couple of decades ago, being described in words as effusive as Parr’s would have surely made Mr. Mandela proud.

Correction: This article has been updated to reflect two changes: First, there is no record of Nelson Mandela saying that he specifically liked Vin de Constance, only South African sweet wines in general. Second, wines from House of Mandela are not available at Wal-Mart. We aplogize for the errors.