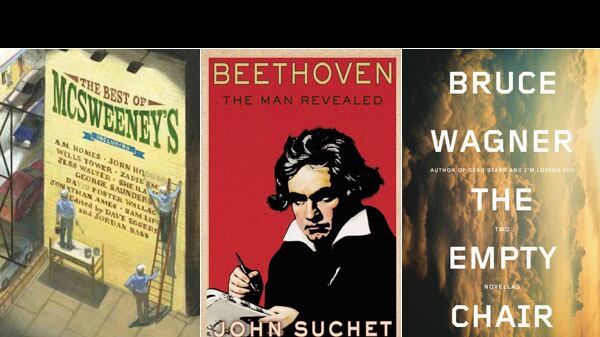

By John Suchet

Scholar John Suchet has written six books about the classical music’s most revered composer, Ludwig van Beethoven; his latest, out now, is Beethoven: The Man Revealed. Suchet himself admits that he has not uncovered any new information about the oft-written about composer; however, his focus on Beethoveen the man is departure enough to justify his book’s existence. The most interesting facet of The Man Revealed is Suchet’s investigation into the interlay between Beethoveen’s life and his art, the relationships that were so strained by his volatile genius inspired some of his greatest work. The transcendent symphonies, far from being the result of effortless genius, were endlessly labored over and sacrificed for—as much by Beethoveen’s family as the man himself. Suchet’s interest lies primarily in the process of creation and the enigmatic nature of genius, which makes the book accessible without ever being reductive. Suchet never gets mired in the minutiae of musical composition, but rather, focuses on the people who were subject to the tyranny of Beethoveen’s creativity. The resulting portrait is of a man who was at once dedicated to and dominated by his own artistry, who sacrificed his personal happiness for his singular musicianship.

—Thomas Flynn

By Bruce Wagner

Bruce Wagner’s 2012 novel Dead Stars was the most depraved read of the year; Wagner’s Los-Angeles is a Hieronymus Bosch painting with paparazzi. In his new pair of novellas, published together as The Empty Chair, Wagner trades the L.A. setting for Big Sur and India, but loses none of the gonzo weirdness that makes his work so distinctive. In “First Guru,” a father wrestles with the suicide if his son, which may have been inspired by his militant Buddhist guru of a wife. In “Second Guru,” a former hippie tells her own story of fanatic Buddhism, centered around a mysterious Bombay holy man known only as “The Great Guru.” To say anything more about either novella would spoil Wagner’s consistently surprising twists and out-of-left-field revelations. Of course, none of his narrative acrobatics would work if he did not populate his world with characters whom elicit genuine interest and sympathy from the reader. Wagner, as irascible and cynical as he can be, is a subtly empathetic writer. The Empty Chair’s jokes, good as they are, prove less memorable than Wagner’s explorations of loss and spirituality.

—T.F.

Edited by Dave Eggers and Jordan Bass.

When Dave Eggers founded Timothy McSweeney’s Quarterly Concern in 1998, the conceit of the literary journal was that it only published pieces that had already been rejected by other magazines or journals. For reasons of practicality, Eggers and co. abandoned this restriction early on, but very much retained that aesthetic, publishing stories and curiosities that were notably distinct, fresh, and sometimes just plain weird, while also featuring some of the best work from the most notable authors of the day. Lydia Davis’s “An Oral History With Hiccups,” a story told with letters intermittently omitted where the speaker is hiccupping, is collected here alongside stories by David Foster Wallace, Roddy Doyle, Jonathan Lethem, Zadie Smith, and many, many others. This remarkable 624-page hardcover is a delightful tome to settle in with; the stories are alternately funny and poignant, brief curios or bracing examples of short form drama. There are even some comics included. Though McSweeney’s has become a premiere outlet to publish new fiction, that has not stifled their offbeat curatorial aesthetic.

—T.F.

Uncharted: Big Data as a Lens on Human Culture

By Erez Aiden and Jean-Baptiste Michel

Have you ever wondered when the phrase “have sex” became more popular than “make love”? Questions like this, regarding how cultures change over time, led Erez Aiden and Jean-Baptiste Michel (with Google) to create a tool that provides some answers: the Google Ngram Viewer. The program allows anyone to pick a word or phrase and instantaneously discover its usage trajectory in millions of books published since 1800. Launched in 2010, it has received critical acclaim, and in Uncharted, Aiden and Michel detail their story alongside the program’s numerous findings and applications. In seven short chapters, they use “cold, hard statistics” (asserting this removes human error and bias) to explain results on topics ranging from the “half-life” of irregular verbs to Nazi censorship. During an era in which Facebook, Twitter, and Google Glass store more information about humans than can be found anywhere, at any point in history, Aiden and Michel implicitly claim, rather presumptuously, that they are the Columbus/Galileo/Darwin fusions who will help make sense of this abundance of data. But it quickly becomes clear how their biases so blind them that they fail to ask far more critical questions. Regardless of whether or not some information remains secure from companies or governments, shouldn’t we seriously consider if preserving “everything” is actually beneficial or even healthy? Instead, the writers appear too entranced by the sheer magnitude of their data-set (and seemingly want it even larger). Constantly indulging in cliché-ridden word play (“To Word or Not to Word?”), they supply mostly cocktail-party anecdotes that gesture weakly toward their utopic vision of reuniting the sciences and humanities via Big Data analysis such as this. But quantifying culture so heavily risks erasing the very richness of language and human experience the authors continually say they cherish. While quickly learning the history of a word accelerates research, such tools tell us nothing about what an individual feels when using that word or the memories it evokes. Regardless of how neutral numbers themselves may be, their human interpreters always carry their own biases. And so as much as Aiden and Michel may think otherwise, they are not merely innocent messengers presenting the results of computers.

—Charles Shafaieh