When a major department at the Metropolitan Museum puts on a show of over seventy works by thirty-five living artists across a huge sprawl of gallery rooms, you know you’re witnessing a Significant Cultural Moment. You’re in the presence of an overarching curatorial statement or argument, one composed of artworks. Usually, the mission involves overturning received assumptions, breaking down preconceptions about genre boundaries, cultural norms, and the like. Generally such a show takes aim at an implicit set of conventional notions, namely yours, and wants to shake them up. It wants to tell you that, while you weren’t looking, the world changed. Your views are too rigid. Time to get with it.

All of which is precisely true of “Ink Art: Past as Present in Contemporary China,” a blockbuster presentation inspired by, but not necessarily composed of, ink-on-paper works which are displayed throughout the traditional Chinese wing of the Metropolitan Museum. And here, already, in the show’s very location, viewers are confronted by the first ‘subversive’ juxtaposition.

“There’s so much excitement and hype around contemporary art, the western variety, so we wanted to show that it’s happening in Asia too, that it’s happening even in the most traditional of forms—that Asia has a cultural present as well as a past,” says Maxwell Hearn, the curator and head of the Asian Art department. “And where can one say that more arrestingly than in the historical galleries?”

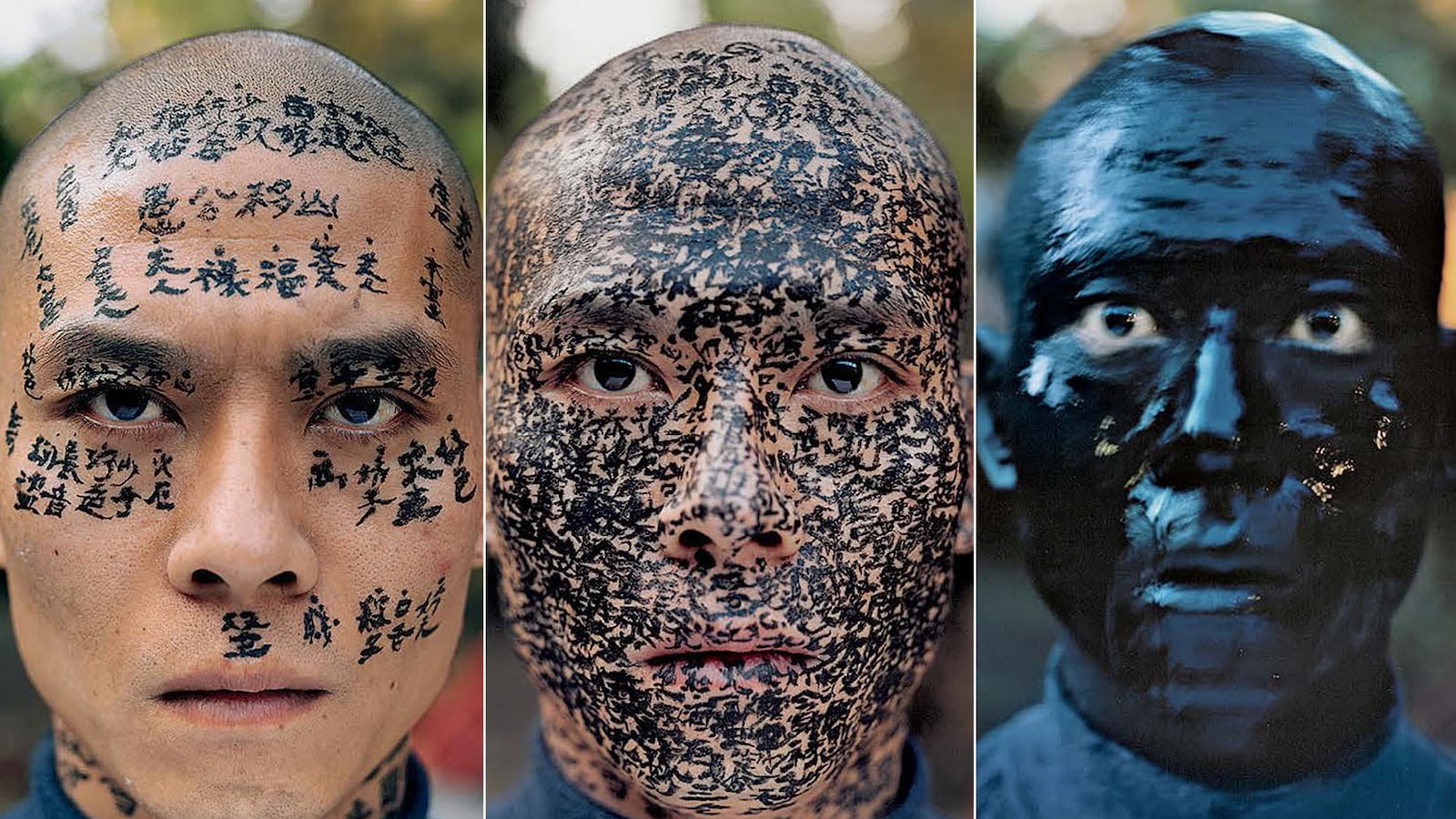

The shock of the unexpected is, emphatically, part of the message. Imagine you’re a regular, unsuspecting Met-goer dropping by for a soothing dose of Ming vases and Literati scrolls depicting mountains. Instead, you find your favorite objects displaced by a cacophony of contemporary works, often highly avant-garde and challenging. Or, conversely, you are lured in by the promise of traditional Chinese aesthetics extended into the present: modern versions of placid misty landscapes, rock-faces, and calligraphic studies, but you’re ambushed by polychrome cityscapes, photorealist images, photos of tattoo art and body painting, and unreadable calligraphy. Perhaps, you come in to see some of Ai Wei Wei’s works, and you’re mystified when you encounter ceramics by him that seem gratuitously included.

The curators have set out to show that art in China, even the most purely homegrown Chinese genre of ink-art, is merging with global influences and creating astonishing, vibrant hybrids that both illuminate the native tradition and expand the collective consciousness. At its profoundest, the show awakens us to what is happening to national cultural aesthetics everywhere, including our own, as motifs and symbols and visual paradigms wash back and forth across divides.

The first stunning foretaste of the exhibit’s leitmotif comes in the form of Gu Wenda’s huge, hanging, single Chinese characters from the mid-1980’s. The work is entitled “Mythos of Lost Dynasties,” and the blurry, inky ideograms play with the notion of a monumental script that gets deified and then fades. This being an artwork from the early post-Mao time of newfound freedoms, one can imagine the implied commentary on propaganda homiletics that lose their relevance and turn opaquely visual.

Other big-name artists explore similar themes. From the 1990’s, Xu Bing’s ideographic renderings of English words bunched up to look like Chinese characters, executed in the brushwork styles of Ming and Song dynasties, explore inter-cultural fusion and confusion. The artist spent part of that decade at the University of Wisconsin, and his art expresses the reverence and alienation of language created by distance. An entire room is devoted to his deservedly famous, magnificent “Book From The Sky,” a vast scroll that hangs across the ceiling and down the walls, block-printed with an entirely invented language made of fake Chinese characters. Wang Dongling’s black-on-white massive almost-characters stretching to abstraction tell a parallel story of form and meaning diverging into mysterious shapes.

These artists and others, including Ai Wei Wei and Zhang Huan whose photo of his face overwritten by Chinese letters serves as the catalog cover, all had their U.S. debut over the years at Ethan Cohen’s pioneering eponymous New York gallery. Cohen’s mother, Joan, wrote the first book on Chinese contemporary art and his father, Jerome, launched the Chinese law department at Harvard and advised Kissinger on the famous Nixon trip to China. Ethan Cohen says, “they [the artists] represent a moment when received notions of beauty and of expression broke open and let in the world of experimentation, a kind of Stravinsky’s ‘Rite of Spring’ moment.”

This questioning of form can be seen in a number of works that substitute cityscapes for the traditional landscape studies of artist-scholars through the centuries. Perhaps the one that makes its point most concisely and indelibly is Yang Yongliang’s “A View of Tide” from 2008. As you stare at the protean work, the massive, fake, ink landscape fools you. You realize you’re looking at a digital photomontage of an urban silhouette crafted into swirling, shadowy hill-shapes with high-rises transformed into rock faces. The artist has witnessed China’s countryside everywhere overrun by development and is trying to find beauty in the content by imitating a millennium-old form. This, one realizes, is the kind of subtly radical morphing of the environment that challenges and unsettles a billion minds every day.

By any measure, the Met exhibition offers some great masterpieces even by traditional criteria. Liu Dan’s “Ink Handscroll” (1990) for example, gives us a long unfurling of the elements in grand and minute detail. It demonstrates the greatness of ink-painting as a genre if it had evolved in a straight line from the past. Yet the show has gotten a deal of negative criticism for being inchoate, unselective, too rambling, and uneven. The New York Times’ Roberta Smith blamed the flaws on Maxwell Hearn being more familiar with classical than contemporary art.

Still, according to Ethan Cohen, “we should all be grateful that the Met, however belatedly, has now acknowledged that living Chinese artists have arrived in the world. Since the death of Mao, there’s been a huge renaissance in the visual arts there. Mr. Hearn has touched on the tip of the iceberg.” One could argue, in the curator’s defense, that hit-or-miss standards of quality always pervade times of experimentation, and the show remains true to the adventure. The Met’s show reflects a phenomenon that remains, in reality, a work in progress.