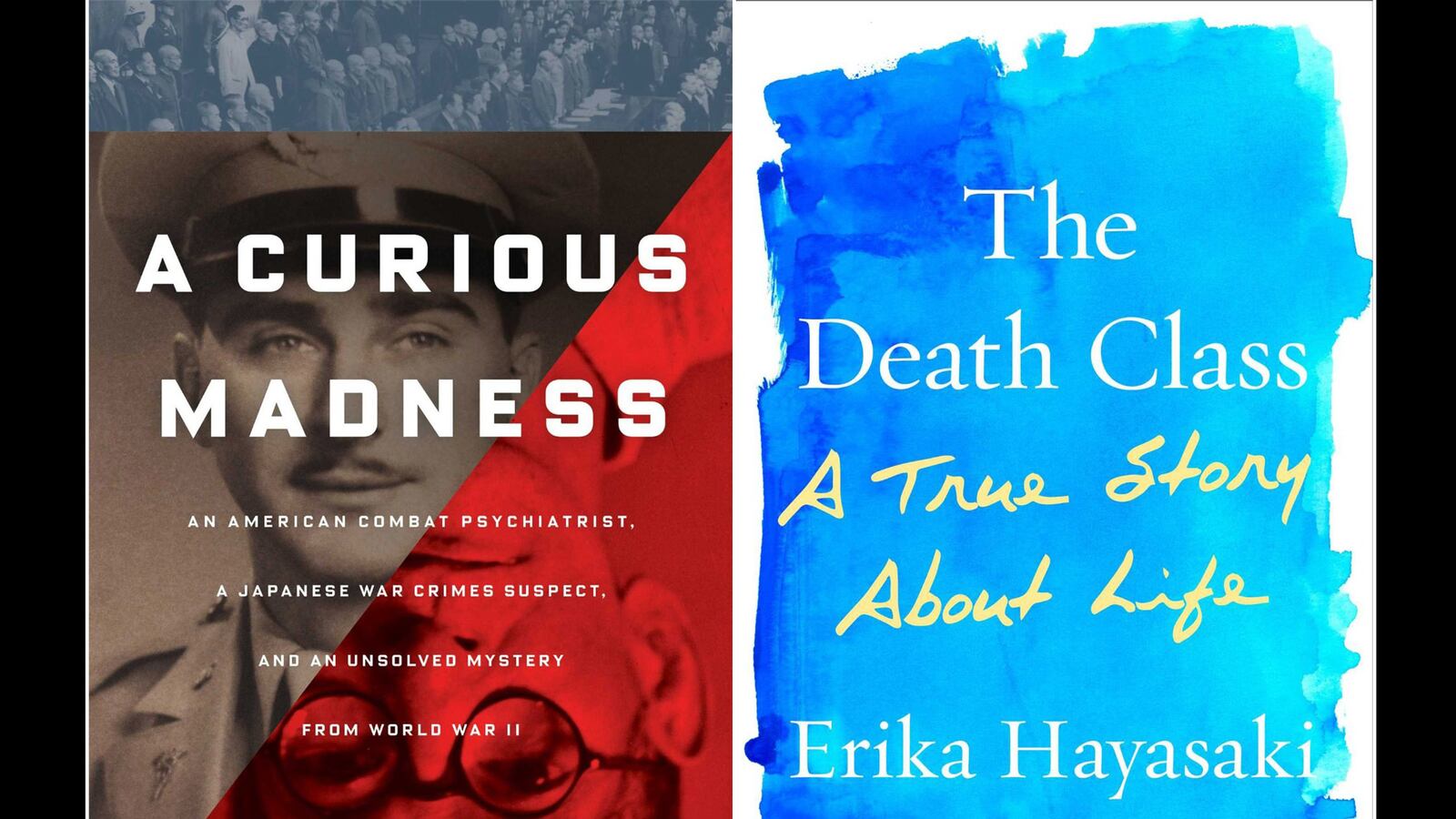

A Curious Madness is not your typical mystery. There is no body, there is no weapon, and unlike a drop of blood, the clues are as nebulous as the thoughts and intentions of men. “The main problem with writing about my grandfather was I didn’t know anything about him,” author Eric Jaffe writes of Daniel Jaffe, who was a combat psychiatrist in World War II. “He shared so little throughout his life and left only scraps to posterity. My only option was to start at the shell and scrape inward—to analyze the psychoanalyst.” Jaffe faces a similar challenge when it comes to writing about Okawa Shumei, his grandfather’s most controversial patient. Prior to World War II, Shumei was a brazen philosopher who envisioned a Japan that was free of the West; by 1946 he was a war crimes suspect accused of being “the brain trust of Japanese militarism.” Okawa faced prison, or worse, but was acquitted on the grounds of insanity after behaving strangely in court. Many believed Okawa put on an act to dodge his fate (the nine other defendants were either imprisoned or hanged); but Daniel Jaffe did not. Hoping to understand his grandfather’s diagnosis, Jaffe constructs a pair of illuminating, if wandering, portraits: one bends through Brooklyn, where Daniel Jaffe was raised by his Ukrainian Jewish mother, who fled the pogroms only to suffer psychotic delusions; the other follows the rise of modern Japan, where Okawa developed his nationalistic ideas in response to western hegemony. In stylish, effortless prose, Jaffe plumbs interesting depths—was Okawa an “ideological villain” or a psychological casualty of war? Is madness contagious?—but what he’s really after eludes him. “We stood there in the dark for a few minutes more…” Jaffe writes, reflecting on a visit he made to the philosopher’s grave with Okawa’s great-nephew. “They had ghosts in the shrines of their ancestors, too.”

The Death Class: A True Story About LifeErika Hayasaki

Forget the classroom. Students lucky enough to get a spot in “Perspective on Death,” a class taught by Professor Norma Bowe, at New Jersey’s Kean University, go on the unlikeliest of field trips: to autopsy rooms; to funeral parlors; to cemeteries, hospices, and the sites of mass shootings. Such a class may seem morbid, but you can’t deny it’s practical application. “For much of the early twentieth century, talking openly and honestly about death was considered poor taste—especially inside classrooms,” author Erika Hayasaki writes in The Death Class. “But by the 1960s, some scholars had come to believe that death education was as important as sex education, if not more important—since not everyone had sex.” Herein lies the conceit of this book: that death, like sex, is taboo, a subject about which we cannot openly speak—or in Hayasaki’s case, report. A lifelong journalist, Hayasaki recalls being admonished by a teacher for a story she wrote in her high school paper about a childhood friend who was murdered: “‘How could I have published such gory details about classmates murder?’” Hayasaki remembers the teacher asking. “It was then I realized how taboo the subject of death was and how people were scared to face it.” Now, decades later, Bowe’s class is her goldmine. Not for its syllabus, or its Freudian underpinnings, but because it is filled with students who have experienced death in the most violent and tragic of ways. They have come to this class to learn the “art of survival,” but Hayasaki lingers on the more sensational aspects of their stories—their murderous fathers, their overdosing mothers—then strings them together like pearls, which repel even as they mesmerize (her writing is very beautiful). Hayasaki would have you believe that this is a story about redemption, but because it does less reflecting, and more exposing, it’s really about pushing boundaries—often for the sake of it.