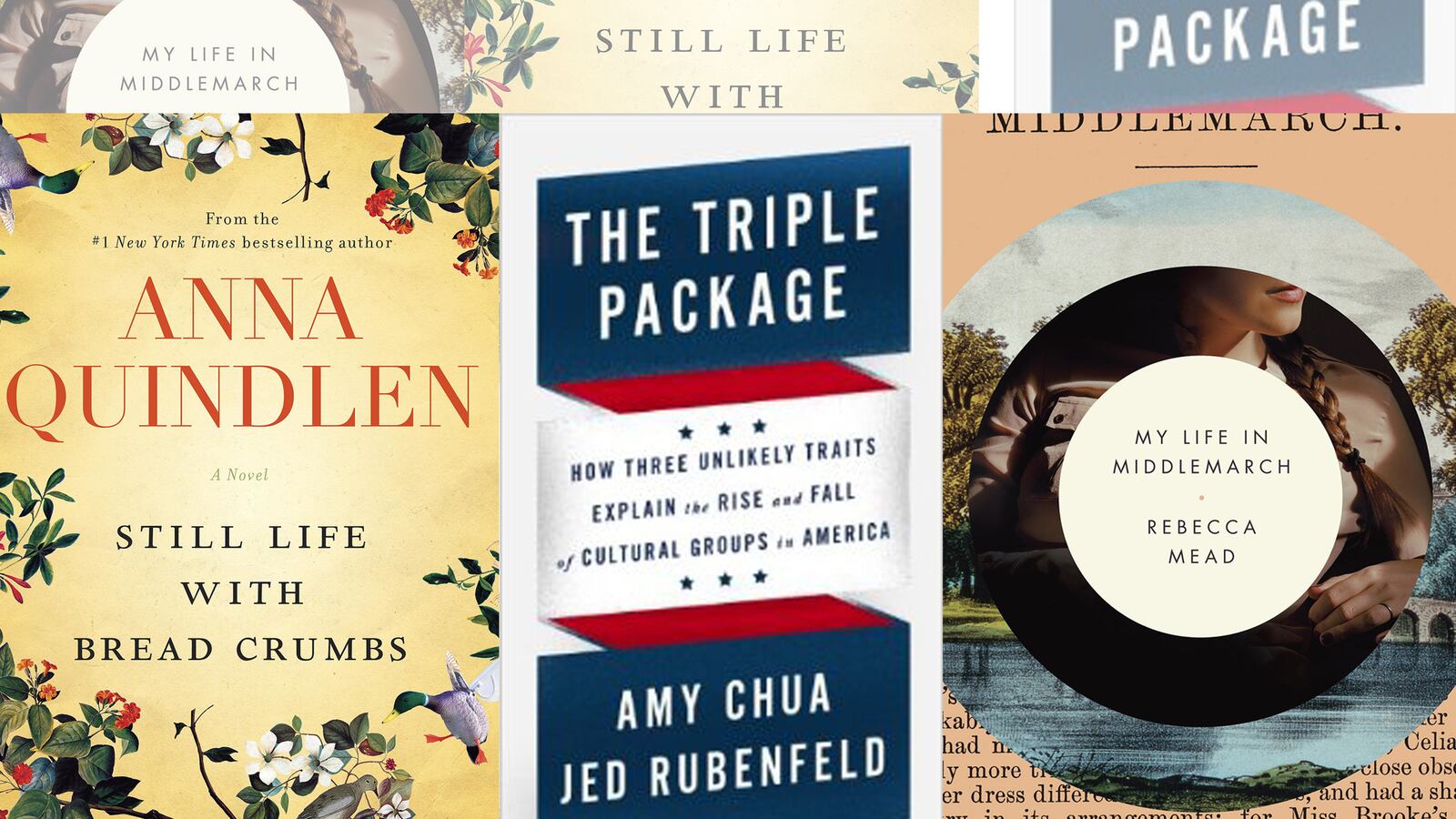

The Triple Package: How Three Unlikely Traits Explain the Rise and Fall of Cultural Groups in Americaby Amy Chua and Jed Rubenfeld

That Amy Chua’s new book, The Triple Package: How Three Unlikely Traits Explain the Rise and Fall of Cultural Groups in America, has, even in advance of its publication, inspired controversy, should come as no surprise. Chua’s previous book, the part-parenting memoir part-parenting manifesto The Battle Hymn of the Tiger Mother, was an unapologetic account (and endorsement) of the strict, decidedly un-American parenting style typical in Chinese culture. It inspired endless debate, countless think pieces, and a neologism that instantly penetrated mainstream culture. Chua, writing with her husband Jed Rubenfeld, clearly hopes her new book can do the same; whether “the triple package” achieves the same Gladwellian ubiquitousness as “tiger mom” remains to be seen, but her frank discussion of race has already made waves. Chua and Rubenfeld have been criticized for proposing that there are superior cultural groups, an assertion made all the more galling because Chua and Rubenfeld belong to two of them: Chinese and Jewish immigrants. The Triple Package, however, is not mere provocation and cannot be dismissed as such. The controversy surrounding the book’s release, and Chua’s own public persona, belie a thoughtful and compelling examination of how culture effects success; Chua and Rubenfeld never propose that a given cultural group is superior, simply more fortunately positioned. Their thesis is that eight specific cultural and immigrant groups (Jewish, Indian, Chinese, Iranian, Lebanese, Nigerians, Cuban exiles, and Mormons) are disproportionately successful because of three specific characteristics shared by their culture of origin—the Triple Package. Each of these groups, Chua and Rubenfeld write, have an entrenched sense of their own superiority as a people; an “inferiority complex” acquired by being marginalized, stigmatized, or otherwise othered; and a culture of impulse control. It is a fascinating theory, written with the nuance and sensitivity that such a fraught topic demands.

Still Life Bread Crumbsby Anna Quindlen

Anna Quindlen’s seventh novel, Still Life With Bread Crumbs, finds the 61-year-old novelist and Pulitzer Prize winner wrestling with aging, art, and the intersection of the two. Rebecca Winter is a photographer, divorced and on the wrong side of 60, her onetime fame slowly dwindling. Her royalties from her masterpiece, an iconic photograph, the titular Still Life With Bread Crumbs, have dried up, and she is forced to move out of New York City and upstate to a leaky cottage in a provincial small town. Her modest celebrity and Manhattan snobberies alternately isolate and endear her to the locals. There is a love story, light humor, and meditations on loss and regret; most interesting, however, is when Quindlen gets in the head of an artist who has become admired and respected but no longer fashionable or relevant. These passages feel the most lived in; aging, for Rebecca Winter, is less frightening than obsolescence. Quindlen makes the plight of the over-the-hill legend compelling and sympathetic—each insecurity and moment of self-doubt ring painfully true. It feels as if the novelist herself has, like all artists, had to confront irrelevance. The resulting novel is a work that feels personal, intimate, and honest. Though Quindlen may write about irrelevance, her latest novel is anything but.

My Life in Middlemarchby Rebecca Mead

Rebecca Mead’s new literary memoir My Life in Middlemarch is a book about the lives—and inner lives—of three women. First and foremost, it is about Mary Ann Evans, the ambitious young journalist who would become George Eliot and write Middlemarch, the novel Virginia Woolf famously called “one of the few English novels written for grown-up people.” My Life in Middlemarch examines the private life of the greatest chronicler of private life, and Eliot’s own abortive relationship with the philosopher Herbert Spenser, and her later, longtime partnership with George Henry Lewes, are recounted here in affecting detail. Eliot’s frustration at the passionless Spenser, and her love for the devoted Lewes, are found in her letters, her diaries, and, most interestingly, in the pages Middlemarch. Eliot’s heroine, Dorothea Brooke, has two very similar men in her life. Her resentful and unloving husband Edward Casubon, and the idealistic but impoverished Will Ladislaw. Dorothea’s frustrated ambition is the quiet struggle of Eliot’s “home epic;” much of Mary Ann Evan’s youthful ambition can be found in Dorothea, and it is in Dorothea that so many readers find kinship. As much as My Life in Middlemarch is about Eliot, and about her most enduring heroine, it is also about Mead herself—her own romances, in which she finds parallels with Dorothea’s, and her own ambition as a writer. The highest compliment that Mead can be paid is that My Life in Middlemarch captures the thrill of reading Eliot, and will no doubt inspire an umpteenth reading of Middlemarch.