“Africa was a big place, and would offer its own suggestions.” Paul Bowles put it that way in Let It Come Down, a title taken from a Shakespearean assassin just before he strikes. Bowles called the title “succinct and brutal,” a fine description that happened also to capture and map an idea of a place: then, Africa. Susan Minot’s mapped many places in her career, many of them interior, but her new novel, Thirty Girls, is also set in Africa, and describes an American journalist’s affair while there alongside the story of girls conscripted into a warlord’s army. It’s a book about the relativity of pain; the grace of forgiveness; and the essential unknowability of a lover, how unknowability’s relation to love is perhaps, if ironically, axiomatic. We talked, then emailed.

How did you first become interested in Africa?

I first travelled to Africa at the end of 1996 and was immediately captivated. I had planned on a three-week trip and I ended up staying two months. Some places inexplicably strike you, though I am certainly not the first person to feel this way. There is a phrase for the foreigners' rapture: mal d'afrique.

Was there other fiction about that part of the world you read while thinking about the novel, or while writing it.

Before going to Africa I had read [Isak] Dinesen's account of her life there and the amazing My Traitor's Heart by Rian Malan, both powerfully affecting. After going, I read more great books about the continent. For some reason everything was non-fiction: West with the Night by Beryl Markham, The Emperor by Ryszard Kapuncinski, North of South by Shiva Naipaul, The Zanzibar Chest by Aidan Hartley, Don't Let's Go To the Dogs Tonight by Alexandra Fuller, Mukiwa by Peter Godwin, Philip Gourevitch's book on Rwanda. There were a couple of novels by Maria Thomas. But while I was writing the book I stayed away from books about Africa. Some of the writers I looked to as guides were Tolstoy, David Foster Wallace, Emily Dickinson, Alice Munro—none of whom you can see in the book.

What drew you to the story of child soldiers, and Joseph Kony.

At a dinner party in New York City I heard the story of a group of girls being kidnapped from their Catholic boarding school in the north of Uganda and led off into the bush by bandits. A nun who taught at the school followed them and managed to bring back 109 of the girls but had to leave thirty selected girls behind. The story was told by the mother of one of those thirty girls. It sort of smacked me in the face.

You wrote about Kony over ten years ago, in McSweeney’s. That piece—“This We Came To Know Afterward”—was non-fiction. Can you say a bit about why Kony kept a hold on you, and why when you returned to him as a subject you returned with fiction. Perhaps you can contextualize other writing about Kony, too; he’s not an obvious popular subject, yet he’s attracted other authors, and since you first looked at his story he’s attracted and horrified the world.

It was not so much Kony who kept his hold on me; it was the children whose lives Kony affected and ruined and the astonishment that he was not stopped. The story which appeared in McSweeney’s was originally commissioned by Harper’s Magazine but killed after a nearly identical story appeared at the same time in the New Yorker. “Our Children Are Killing Us” was an excellent piece by Elizabeth Rubin—a proper journalist—who went on to win a Livingston Award for International Reporting in 1998 for it. I recently heard that Rubin is working on a book; it’s called Chasing Kony. The story apparently kept its hold on her, too.

In the new Foreign Affairs, in a piece called KONY20Never (and maybe you can comment on that title), Peter Eichstaedt writes:

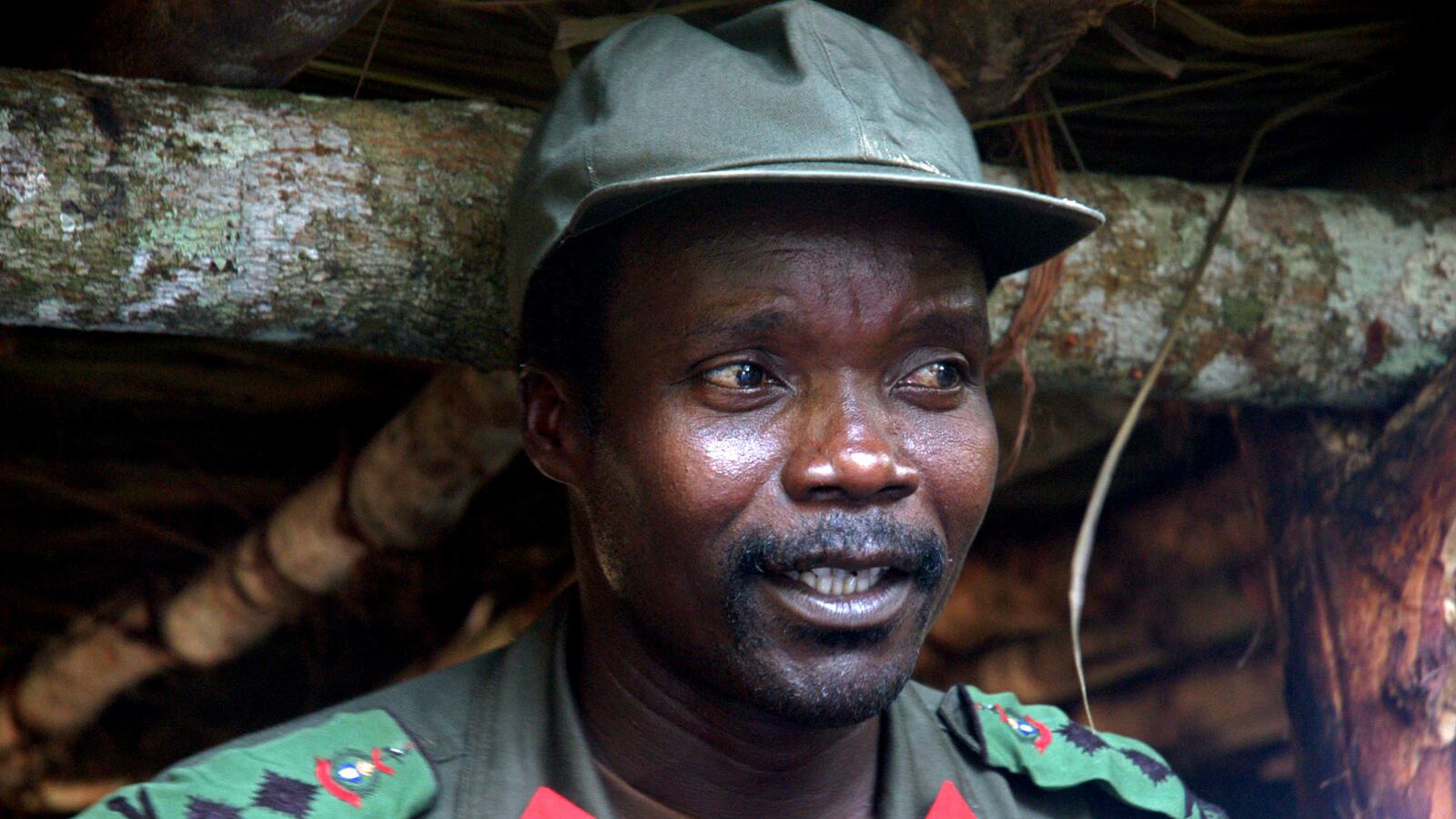

Kony is many things—a megalomaniac, a self-proclaimed prophet, a witch doctor, a spiritual medium, a ruthless and paranoid commander. But above all, he is a survivor.

What do you think about that assessment, about “self-proclaimed prophets.” And why can’t we capture Kony.

Kony is certainly self-proclaimed. I would suggest we can’t capture Kony, because no one has wanted to enough. Therein lies a whole other story.

How did the novel evolve away from your original idea of it, and can you say something the editorial process, the paring away.

The novel evolved, or at least changed, a lot from the original conception which was first, just the story of one of the abducted girls. It expanded into focusing on more of the abducted girls, then I thought I would add the journalist Jane, then I had the hope that more of Uganda’s history would be included, then pulled back on that—etc., etc. In other words, I kept putting in and taking out. I was also aware of how much one might ask of a reader in terms of taking in horrible stories—and there are plenty of those stories where Joseph Kony is concerned—so I tried to measure that as well.

Your use of the second person in interstitial sections of the novel is so powerful, and unique. In one of them, you write:

Who said you choose your life? You have gone away and new things test you. Wind, hands. Some cruel, some kind. There is madness in the dark and madness in the morning with the smell of smoke. You wade in the water, walk on your knees. Sometimes they take your hands and bind you. No one looks you in the eye. You listen to what they say, some is true, some not. You meet yourself before falling asleep. You may have been gone from yourself all day but you are there when you close your eyes. You lie on the leaf of yourself and sail into dreams. People there fly. You may not be able to steer, but at least you are able to bear it.

Can you say something about these chapters, and about the choice of the second person?

My original idea was to have a sort of Greek chorus appearing more frequently throughout the book. At first these appearances came in the form of small anecdotes (mostly about the rebels), or were Kenyan news reports. Then, as was true of the process undergone by much of the writing the novel, the anecdotes became more interior and started to take on the second person. Eventually I made it all the second person. Turns out—and this is rather strange—the second person proves to be more interior than the first person. I started to think of these sections in part as being the interior place where the characters of Jane and Esther perhaps overlap. Nearly all the text could be spoken from the point of view of either. Nearly all, for that matter, could be questions (though this recognition came after) that the reader might possibly ask of herself. The title of those sections—The You File—acknowledges the fact that the computer was involved in the book’s final drafts. This was the first novel of mine put, eventually, on the computer. I am not sure I will do that again.

How did you think to marry a story about horror, and Kony, with a story about love.

It, too, evolved. The first part of the evolution was the awareness that to write only about horror and the brutality of Kony might not be the most inviting subject. I was also thinking of the disconnect we accept in many books, of only showing one version of life . . . that is, if war is the subject, the more trivial aspects of life are not included, for seeming to be less pertinent or even important. Children being brutalized is certainly of greater moral concern than a woman yearning for love, or the idle thoughts which pass through the mind while more weighty things are going on, but both things exist in the world, in the same world. That they are side by side is interesting. So I was trying to reflect that and not avoid the uneasiness inherent in the depictions of different existences.

On this, and on the variations of pain, you mentioned a passage in War and Peace that was a kind of touchstone. Can you describe that passage and why it is meaningful—both for Thirty Girls and perhaps for fiction more broadly.

The Tolstoy passage is when Pierre is a prisoner of war and on the miserable march back to Moscow in the winter. People are dying around him daily and he manages to separate himself from where he is. He has a big revelation: he recognizes that suffering is relative, and understands that the suffering he feels now with bare feet and sores so painful he thinks he cannot walk another day--then does-- is no different than the suffering he felt putting on his tight ballroom slippers. He also recognizes that just as there cannot be absolute freedom, he sees there cannot also be absolute enslavement.

The passage contradicts the knee-jerk reaction which wants to quantify suffering. Certainly if one recognizes all suffering as valid, one should be able recognize that all experience is worth considering. “He learned that there is nothing frightening in the world.” He was showing a great acceptance for everything in life. I would propose that this might be a good guide for fiction.

Here is the passage:

In captivity, in the shed, Pierre had learned, not with his mind, but with his whole being, his life, that man is created for happiness, that happiness is within him, in the satisfying of natural human needs, and that all unhappiness comes not from lack, but from superfluity; but now, in these last three weeks of the march, he had learned a new and more comforting truth—he had learned that there is nothing frightening in the world. He had learned hat, as here is not situation in the world in which a man can be happy and perfectly free, so there is not situation in which he can be perfectly unhappy and unfree. He had learned that there is a limit to suffering and a limit to freedom, and that those limits are very close; that the man who suffers because one leaf is askew in his bed of roses, suffers as much as he now suffered falling asleep on the bare, damp ground, one side getting cold as the other warmed up; that when he used to put on his tight ballroom shoes, he suffered just as much as now, when he walked quite barefoot (his shoes had long since worn out) and his feet were covered with sores.

As we’re on Tolstoy, what do you think about Anna Karenina, speaking of devastating love stories that interweave philosophy and ardor.

I love Anna Karenina. It’s in the top five books on my list. Tolstoy is unsurpassed in combining the grand with the trivial, that is, the small details which make up life.

Are there limitations to writing about love?

Of course. Primarily it is the limitations of words. But one must keep trying! I have found in other writers portals into the understanding of love that may not have appeared so clearly in my life. I am not sure how helpful that is, except that the communing certainly keeps us from feeling totally isolated in our perplexity. Writers are able to offer more particular wisdoms about particular aspects of love, according to his or her character and nature. Some, like Shakespeare, seem more vast than particular. But Rumi’s depiction of love is far different from Virginia Woolf’s.

Is there an element all great love stories share?

I bet you have an answer to this; I don’t. That they remain unrealized?

Are there limitations to writing about sex?

Much more limitation in writing where sex is involved. But there is a lot that can be conveyed about attraction and drive and everything surrounding the actual physicality of it. Much of sex goes on in the mind, even if it enters through the body. Writing about actual sex is as hard as writing about music and how it sounds to a person, or about dance and trying to convey how a dancer moves. (Film can go there triumphantly…) Writing chases after the senses and conveys them in an altered form. When it is done well, the senses come alive in a new and captured form.

What kinds of writing interest you now, and is it a different kind of writing than interested you when you were writing your first novel.

Good writing most interests me now. That is, beauty and clarity in the prose. When I was younger I suppose I was interested in checking out as much about writing as I could, bad, weird, irritating, even things not-to-my-taste. Now I am less open. I will decide after a few pages if I want to stay in the world of the book and if I don't, I put it down. I have less time left.

What can the novel do that non-fiction can’t?

Go inside. Make things up. Above all, fiction can give you the feeling, which life so often has, of being disorienting and not-according-to-a-plan and illogical and truly mysterious and full of wonder. Non-fiction can convey these things, but it's not part of its job.