Editor's note—On Sunday, Feb. 1, Egypt released Al Jazeera journalist Peter Greste from prison, where he had been held since 2013 along with his colleagues Mohamed Fadel Fahmy and Baher Mohamed. Greste, an Australian, was technically extradited rather than freed, and his lawyer said Egypt expected him to be tried in Australia for the crimes he was accused of. The Daily Beast is reposting this piece on Greste as he tastes freedom and his colleagues continue their wait.

Right now, journalist Peter Greste is being held in solitary confinement in Cairo’s high-security Tora Prison, and could face another seven years behind bars. But ten years ago, he was documenting the unexpected love between a hippo named Owen and a tortoise named Mzee that would become a worldwide sensation. And for decades before that, he was taking in strays from the street and providing them with a good home—despite his parents' protestations.

Since Dec. 29, the Australian-born Al-Jazeera reporter has been imprisoned in Egypt along with two colleagues on charges of broadcasting “misleading” news, aiding the Muslim Brotherhood, and tarnishing Egypt’s reputation. “It's a rap sheet that would be comically absurd if it wasn't so deadly serious,” Greste wrote in a letter from prison last month.

Thursday marked the international day of action held in their honor, with activist groups from Amnesty International to Human Rights Watch lobbying for their release. In Australia, a rally called upon Prime Minister Tony Abbott to appeal to Egyptian leader Abdel Fatah el-Sisi for the journalists’ acquittal. Meanwhile, the White House has urged charges be dropped.

Last week, 48-year-old Greste and his two colleagues, Mohamed Adel Fahmy and Baher Mohamed, were held in a barred cage of a Cairo courtroom for their hearing, during which they pleaded not guilty and were denied bail. “It was shocking…how you expect animals to be treated,” his brother, Andrew, told reporters. The case, which includes some 20 journalists, will resume in court next week.

Though foreign reporting has defined Greste’s career—including award-winning stints in some of the most dangerous war zones like Somalia, Afghanistan, and the Balkans—he’s also known for a heartwarming series of children’s books following an adorable interspecies relationship.

"Peter always loved animals," says his father, Juris Greste, speaking from what he calls the communications "control center" of his home in Brisbane. He remembers his teenage son begging for a dog despite his parents wishes. One day, he turned up with Gemma, whom he'd gotten from the pound. Years later, working in Buenos Aires, a friend of Greste's nursed a badly hurt stray back to health, who Greste agreed to adopt. "Not just because he wanted to buy a dog, but his love and compassion for all forms of life gave in," his father remembers. "Peter was the sucker as it were," he laughs, and calls Kelly the "most traveled dog in the world," jet-setting along on Greste's foreign assignments. Then, most recently, there was Harry, a stray yellow lab, who passed away last year. Greste was so distraught by the dog's medical troubles he delayed a trip home to Australia by a few days.

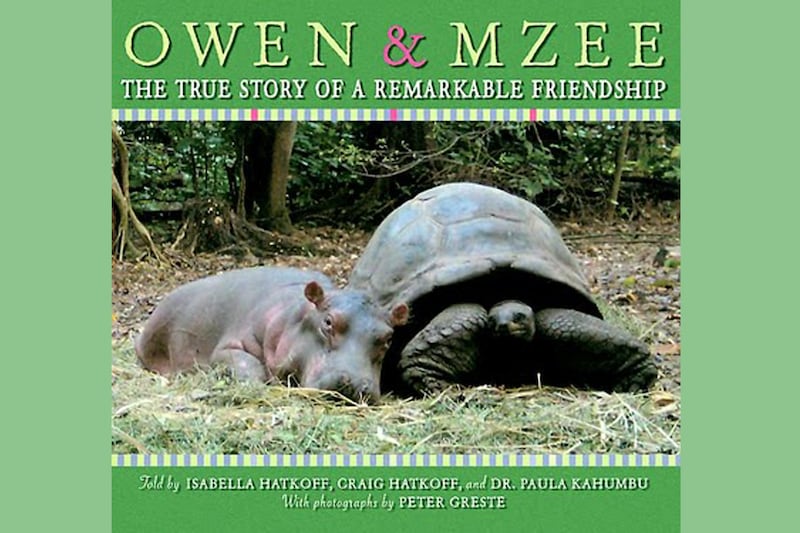

In 2004, a baby hippo lost his family during the 2004 Asian tsunami in Malindi, on the Kenyan coast, and was taken in by Haller Park, an animal sanctuary. Named Owen (after the volunteer who rescued him), the hippo was frightened upon first arriving at his new home, and cowered behind the nearest animal. It happened to be Mzee, a giant tortoise with a whopping 130 years under his shell. Soon an unlikely friendship blossomed, and the animals became inseparable.

Greste, who was then dating sanctuary director Dr. Paula Kahumbu, documented the mammalian-reptilian rapport from its early beginnings. "He loves animals, is also a keen photographer, and enjoyed the whole idea of taking images and contributing to the sharing of a lovely story," his father says. He would go on to contribute his photographs to a series of three books penned by Craig Hatkoff and his six-year-old daughter, Isabella. He also created a short documentary about the creatures’ bond.

“Owen will often stand motionless by his guardian’s shoulder, his head tilted slightly towards Mzee’s,” Greste wrote upon the book’s release. “Occasionally, when he thinks nobody is watching, Owen will plant a sloppy lick across Mzee’s cheek.”

Then, he lent his pictures to “Looking for Miza,” about the last remaining mountain gorillas deep in the forests of Eastern Africa. The book was part of a commitment to the Clinton Global Initiative that would bring attention to these endangered animals targeted by rebel groups. President Bill Clinton lauded the work, saying it “not only tells the story of one gorilla's struggle in the wild, it also shows the danger of human indifference.”

Earlier this month, the Owen and Mzee co-author Craig Hatkoff wrote an editorial for animal site The Dodo about his colleague’s imprisonment. “Hard to believe this is the same Peter Greste who has taken some of the most breathtaking wildlife photographs that have captured the world’s imagination most notably the iconic photo of an orphaned baby hippo being cared for by a 130 year-old giant tortoise in Kenya,” he said. “If only the confused beasts around the world—who can’t tell the difference between journalists and terrorists—would act more like the wonderful beasts that Peter has captured with his camera the ‘negative impact on overseas perceptions’ might actually improve.”

Juris Greste remembers the last time his son was in Australia, he purchased a T-shirt at a craft market with the word "Coexist" spelled out in various religious symbols. This message, his father says, is "quite emblematic of Peter’s personal ethic and professional ethic: accommodate everybody. And that notion and mindset extends to the animal world as it does to humans."

Meanwhile, on the coast of Kenya, Owen and Mzee have since been separated at the sanctuary, after the hippo’s bulk made workers concerned for the aging tortoise’s safety. The two now reside with species of their own kind.

Reflecting on his time documenting Owen and Mzee, Peter Greste wrote: “[I]t it seems to be a powerful sign that all of us—hippos and tortoises included—need the support of family and friends; and that it doesn’t matter if we can’t be near our blood-kin.”

Right now, thousands of miles away from his family in Tora Prison, Greste is certainly grateful for the global support. His father, Juris, says it's the family's "fervent hope" that once the trial resumes the court will realize its lack of evidence and dismiss it in a matter of days. There are certainly enough Egyptian dogs who would be grateful to fill a void left in Greste's life by a yellow lab named Harry.