Back in 2006 when I was interviewing doctors for an article about prescription data mining, few of them knew that it occurred. The ones who did were not happy about it. In fact, the practice of drug companies buying prescription records from pharmacies for marketing purposes outraged enough doctors that several states attempted to ban it. States argued that it drove healthcare costs (drug reps used the data to manipulate doctors into prescribing expensive brand name drugs), and that it was an invasion of doctors’ privacy (patient names were deleted). A Vermont bill, Sorrell v IMS Health, went to the Supreme Court, but it was struck down on free speech grounds.

Sorrell v IMS Health focused solely on prescription data, but it was a major battle in the wider war over data tracking. Had it been upheld, more pro-privacy legislation would have followed, threatening to derail the accelerating data tracking industry -- an industry now worth billions and employing hundreds of thousands of people. As Julia Angwin notes in her new book, Dragnet Nation, the watershed year for tracking was 2001. While the September 11th terrorist attacks gave the NSA its excuse for sweeping dragnets, a federal judge’s ruling earlier that year that DoubleClick’s “cookies” technology was legal opened the floodgates for commercial tracking. After 9/11 and the DoubleClick ruling, Angwin writes, “Finally, Silicon Valley had a business model: tracking."

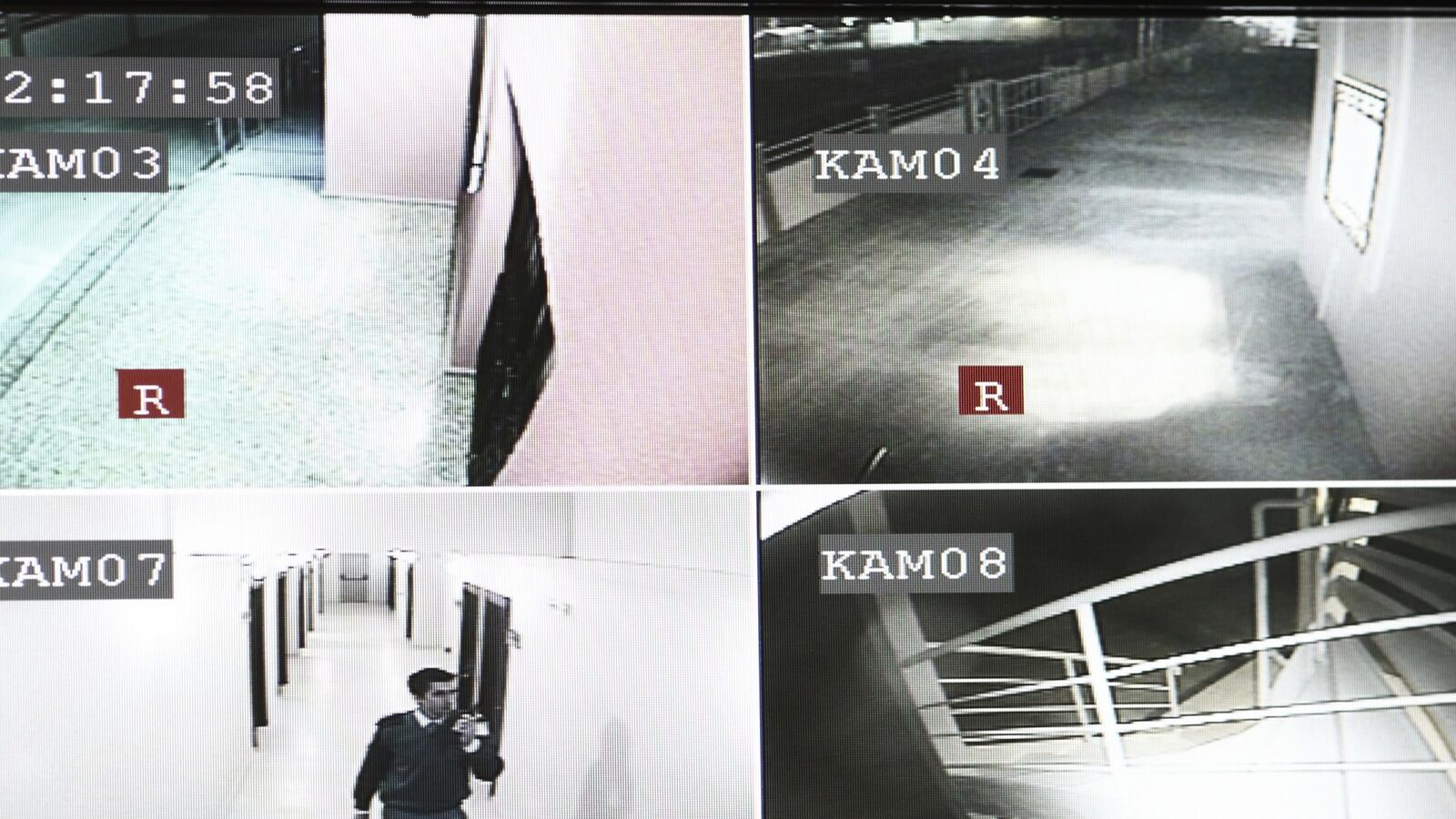

Angwin’s chief argument in Dragnet Nation is that tracking has become so ubiquitous it threatens to turn the U.S. into a repressive surveillance state. (The off-the-shelf surveillance market alone, she notes, has grown from almost nothing before 9/11 into a $5 billion-a-year business.) To make her case, Angwin packs Dragnet Nation with a slew of hair-raising tales: governments and corporations sweeping up data from the Internet, email, cell phones, and new technologies like facial recognition to track, influence, and make predictions about people’s behavior -- in some instances, watching people through their laptop cameras or predicting where they’ll be next week.

The big question, of course, is whether all this tracking is merely annoying or whether it’s a genuine threat. Skeptics say it’s easy to ignore the ads and if you’re not a terrorist, no need to worry about the NSA. But Angwin points to case studies and research that show relentless surveillance is creating a culture of fear that has already begun to chill basic freedoms, such as freedom of speech and freedom of the press. Some particularly unnerving research she cites suggests that covert surveillance causes anxiety and self-repression in adults, and a reluctance to learn in children.

Two recent reports bolster her case. The latest Press Freedom Index, for example, ranked the U.S. 46th out of 180 countries -- 12 spots lower than last year -- partly because of the Obama Administration’s vigor in pursuing whistleblowers through the digital trails of journalists. A landmark 2013 U.N. report on the effects of surveillance found that, “Undue interference with individuals’ privacy can both directly and indirectly limit the free development and exchange of ideas.”

Angwin offers the story of Sharon and Bilal. Both suffering from depression, they became friends on patientslikeme.com, which provided a forum for sharing medical information and personal struggles. One day the site caught an intruder attempting to copy their conversations. It turned out to be the Nielsen Company, a media research firm. Although the site prevented the break-in, patientslikeme told its members what they may have missed in the fine print: the site itself was selling member data to outside companies.

Sharon and Bilal no longer talk online and have withdrawn from the Internet. But beyond the chilling of their free expression are more immediate concerns. Companies increasingly turn to data brokers for information about potential hires, and, “If Sharon or Bilal is denied a job or insurance, they may never know which piece of data caused the denial.” Angwin notes that keyword searches are increasingly tracked. So what about the person researching a friend’s diabetes? Will she pay higher insurance rates because of her searches for “blood sugar”? And the banker writing a novel about hate crimes; will he be denied a promotion because of his frequent searches for “neo-Nazi”?

Because tracking remains opaque, we don’t really know the answers to these questions. To bring greater transparency and protect against abuses, Angwin calls for the creation of an Information Protection Agency. But while another bureaucracy may not be the answer (even the name sounds Orwellian), oversight is clearly needed. Angwin, in fact, sought out her own data and discovered much of it was ludicrously wrong—one broker pegged her as Asian (she’s not), single (she’s married), and hadn’t finished high school (she did). If employment, insurance and who knows what else are going to be determined by the information that data brokers peddle, then, Angwin argues, we deserve a right to view it and have recourse to correct it.

Angwin’s stories about government surveillance are as terrifying as anything in the book, particularly the tale of Yasir Afifi, an American citizen who was harassed by the FBI for a year because his friend made a joke about terrorism in an online forum. But the focus of Dragnet Nation is commercial surveillance—a powerful reminder that the tools of repression are made by the private sector in the name of profit, with the government later exploiting them in the name of security. (The focus on private tracking may also anticipate Glenn Greenwald’s forthcoming book about Edward Snowden and the NSA, due out in April.)

There are stretches in Dragnet Nation that are too obviously designed to scare, and parts feel paranoid. But Angwin’s warning that “information is power” resonates. The Internet, after all, was hailed as the great democratizer: Easy access to information by the citizenry was supposed to move us farther away from any of threat of totalitarianism. But the opposite may have occurred. Angwin argues that by stockpiling vast quantities of our mundane information the “balance of power is shifting and large institutions are gaining the upper hand.” While she’s realist enough to recognize that data is the “oil of the Internet” and has made great technological innovation possible, she urges restraint—and a renewed vigilance by the Fourth Estate.

“As our nation shifts toward an information economy, there are few laws policing the booming industry giants and few governmental or nonprofit institutions with the technical savvy to police the information economy. And so it falls to today’s muckrakers—investigative journalists and conscientious objectors like Edward Snowden -- to reveal the underbelly of the information revolution. I hope that once we see the abuses clearly, we will be able to find a way to restrain the excesses of the information age.”