The author of more than forty books, Jerome Charyn is known in various, not always overlapping reading communities. At King Pong, a table tennis club in lower Manhattan, where this interview began between games with the interviewer, Charyn is known for Sizzling Chops and Devilish Spins, his book on ping pong. In the Bronx, where he grew up, he is known for memoirs set in that borough. Readers of detective fiction all over New York and America know Charyn’s series featuring Isaac Sidel, which began with Blue Eyes in 1975. In France, where Charyn taught for many years, he is recognized for his Sidel books and his graphic novels—and has been named a Commander of Arts and Letters, the country’s highest honor for an artist.

Recently Charyn has been publishing historical fiction: Johnny One-Eye, in which George Washington is a character; The Secret Life of Emily Dickinson, in the voice of the poet; and now his most ambitious project, I Am Abraham, a novel about Lincoln’s whole life narrated by “Honest Abe.” Before this book, I knew more about ping pong than Lincoln, but I’ve been reading biographies to prepare for this interview, and the more I’ve learned the more I’ve come to admire Jerry’s presentation of Lincoln’s psyche and Jerry’s ability to throw for more than 400 pages Lincoln’s idiosyncratic voice. A spry and energetic 76, with a mean underspin forehand, Jerry may write even bigger and better books than I Am Abraham, but in fifty years it could very well be his best known work wherever novels are still read.

Given the time you needed to research Lincoln’s life, you must have been writing I Am Abraham when Spielberg’s Lincoln came out. How did you feel about the timing of the movie and what did you think about its script and acting?

I was disappointed in the movie. I thought that a visual virtuoso such as Spielberg was capable of doing a Gone With the Wind for grownups, and this is what I imagined: the film starting with the Lincoln-Douglas debates, and Lincoln riding out of obscurity to become an almost accidental President, since the Democratic Party was so split. Instead, we have a closet drama surrounding the Thirteenth Amendment, with most of the sound and fury inside the House of Representatives. But Daniel Day-Lewis is splendid as Lincoln, and Sally Field almost as good as the cunning, half-mad Mary.

I was troubled by the trailer, since it seemed to show an image of Richmond burning, and I knew that I wanted to end my novel with Lincoln’s visit to Richmond right after the Rebels have fled, leaving a kind of necropolis in their wake. And I told myself: Jerome, you’re fucked. You’ll have to write a new ending for the novel. Luckily I’m a member of the Screen Writers Guild, and I was able to see an early version of Lincoln. I realized soon enough that the town on fire was Petersburg, and not Richmond, so I’m grateful to Spielberg for that. Of course, it would have been perfect had there been some synergy between the novel and the film, and had both appeared the same season. But timing is always unpredictable, and all the clatter around the film could have swallowed up I Am Abraham.

I hadn’t known what an anecdotal oddball Lincoln was before the movie. Your novel gives considerable attention to his personal life before he became president. What do you think the book adds to the Lincoln portrayed in the movie—and to the Lincoln that many people know only as a mythic emancipator?

The movie offers us a glimpse of the public Lincoln, the teller of tall tales, the politico and grand manipulator, a kind of Machiavelli on the side of the Lord. But Lincoln was a much more sexual man than the movie allows. My novel starts in New Salem, as Lincoln is washed ashore as a young man who has yet to define himself. We see him fall in love with Ann Rutledge, the local bombshell, but she’s engaged to another man. The whole town lusts after her, every bachelor, even those with a foot in the grave. Lincoln courts her in his own fashion, and we have a sexy scene in the woods. Then he has to go off to the State capital. Thinking of Ann, desiring her, he masturbates. “I jerked my own jelly night after night, with spiders and ants as my lone companions in the privy, while I rose above the stink and dreamt of her aromas and red bush.”

Later, he will fall in love with Mary Todd, a Southern belle, and feel much of the same passion, even more: we watch them make love on their wedding night, as Lincoln “reveled in the perfumery between her legs.” Billy Herndon, Lincoln’s first and finest biographer, was convinced that Lincoln detested Mary from the beginning of their marriage. But Herndon is a most unreliable narrator in all things about Mary, since they never got along. Lincoln couldn’t have become President without her. She had to groom this “unparlorable” man, who had a hard time learning how to eat with a knife and a fork: this always endeared me to Lincoln, since I suffered from the same problem. I still can’t eat with a knife and fork…

When Herndon’s biography came out, he was accused of inventing material that would have embarrassed Lincoln had he been alive. It’s more than a hundred years later, but you might receive the same criticism. Could you talk a little about the factual basis for your sexualizing of Lincoln?

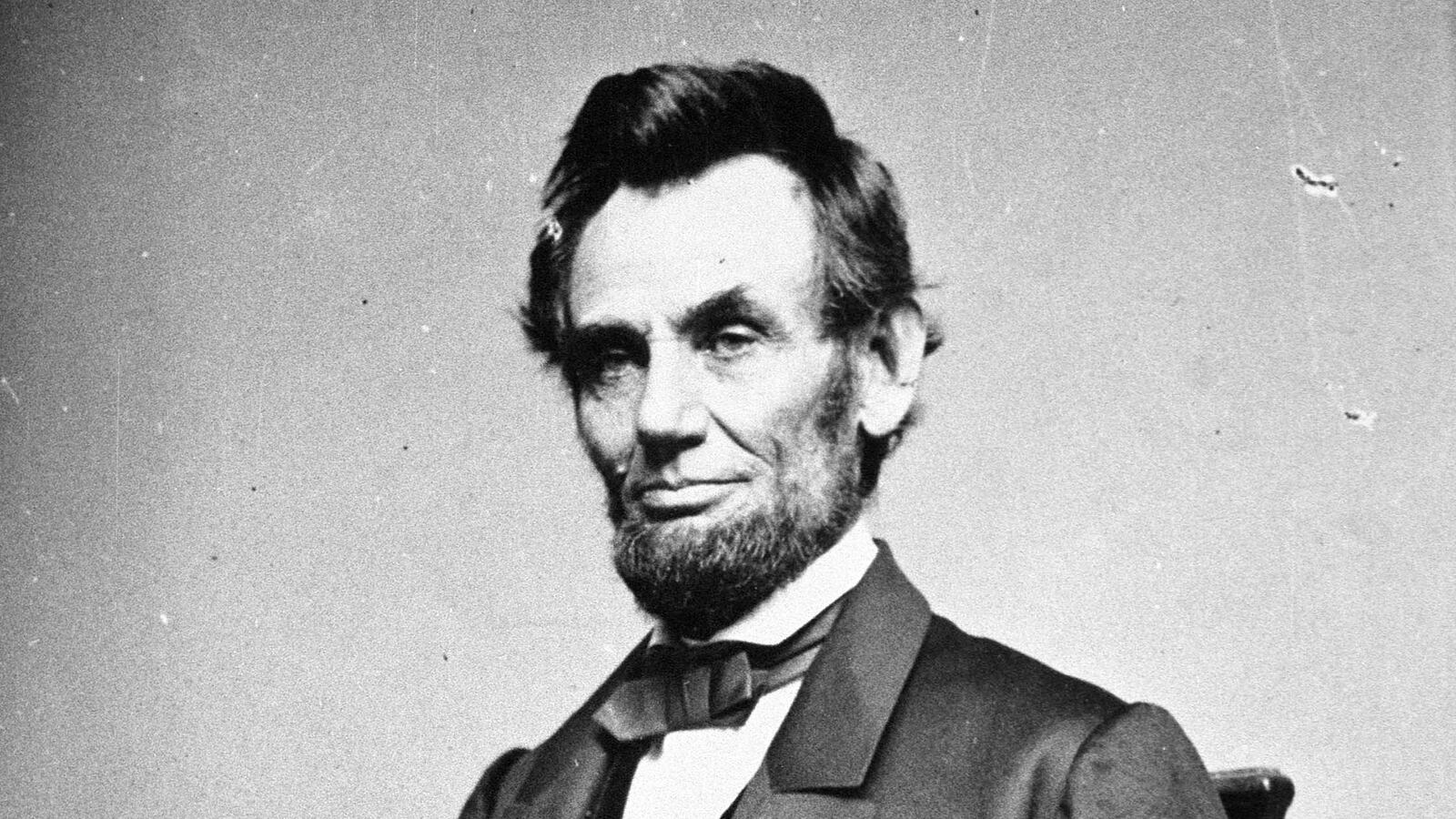

Ah, but then one would have to ask why none of Lincoln’s biographers ever dared deal with his sexuality. Did his sudden, violent death erase him as a man and sanctify him in one savage blow? Saints don’t seem to have sexual organs. We have a few “half-facts” about young Lincoln. He may have visited whorehouses in New Orleans and Beardstown. He may have worried about marrying Mary Todd because he feared he had contracted syphilis. But I couldn’t have written about Lincoln without dreaming my way into his life, inhabiting him like a golem or a ghost. And in my dreams Lincoln masturbated. In my dreams he was a sensual man who also had a hard time moving his bowels. So one can picture him on the privy. But that privy doesn’t appear in history books and neither does his marriage bed. Mary was his “child wife,” his Ophelia, and we have a glimmer of her own sensuality in the daguerreotype that appears on p. 115 of I Am Abraham. She’s in her twenties here, I believe, and I can imagine undressing her with my own hands—in the guise of Abraham Lincoln, of course.

Mary was indeed a comely lass, but please don’t tell me you also imagined undressing the virgin of Amherst when you wrote The Secret Life of Emily Dickinson.

The virgin of Amherst may not have been a virgin at all. When I wrote The Secret Life, I didn’t know enough about Dickinson’s bisexuality. The daguerreotype of her and Kate Anthon—a nineteenth century femme fatale— didn’t appear until after my novel was published. No, I never dreamt of undressing Emily with her own hands or with mine, but I think I would have depicted her ravishing Kate, “a little” (as Lincoln loved to say), if I’d had that daguerreotype, with Dickinson looking like a tigress ready to devour the world.

Okay, enough about sex. What got Herndon in even more trouble with his biography was claiming that Lincoln was a free-thinker and certainly no Christian. What is your considered take on this issue, which was crucial to many in the decades after Lincoln’s death?

Lincoln was never a practicing Christian, though he did believe in the Deity, at least while he was President, when he talked about the war working out some form of divine will. But it’s much more difficult to glimpse into Lincoln’s mind than it is to describe his sexuality. I would trust Herndon’s insights here. He had the most of Lincoln, other than Mary herself. Herndon saw him in the courts, knew him as a circuit rider. In my own opinion, language was Lincoln’s real motor and religion:

“I remember the first words I ever writ—in the sand outside Pa’s Kentucky cabin. I felt the power in my fingernails to brand the earth with my own scrawl.

I am Abraham . . .

I lived in words and would be buried in their fire.”

Your words in the second half of the novel about Lincoln’s conduct of the war could get you buried in the fire from Civil War buffs, who are numerous and learned. Who do you think you will provoke in your treatment of Lincoln’s mostly ineffectual generals?

No one. My depiction of George McClellan is irrevocably accurate. Little Mac was one of the great tragic figures of the war; his soldiers adored him, but he didn’t have the least idea of how to fight. He was a builder of armies, not a battler. He would ride across the District of Columbia on his black horse, Dan Webster, or survey the countryside from a hot-air balloon. He was almost on the verge of treason, as politicians and his own family of officers advised him to march on Washington and get rid of Lincoln. It was Grant, and only Grant, who changed the texture of the war, a general who fed his mules before he had his own supper, and who wasn’t afraid to kill:

“It wasn’t like the days when McClellan first rode into the District… Grant didn’t have an aeronaut, not even a black stallion. He came alone and promised nothing. But there was the quiet of a man who appeared without drums or regimental banners, without the fanfare of military campaigns, just a soldier with his mules and his supplies, wading through the swamps with his men, and arriving under the parapets of Vicksburg, almost by accident, but with deadly design.”

After writing about Dickinson’s life, you must have known the challenges of entering the Lincoln industry—the research required, the competition with recent biographies. So what was it that drew you to Lincoln?

His profound and crippling melancholy, which cast a poetic shadow and moved me almost as much as his accomplishments. Several winters ago, I happened upon a book about Lincoln’s lifelong depression—or hypos, as nineteenth-century metaphysicians described acute melancholia—and suddenly the image I’d had in my mind of a backwoods saint vanished; now I had a new entry point into Lincoln’s life and language—my own crippling bouts of depression, where I would plunge into the same damp drizzly November of the soul that Melville describes in Moby-Dick. But I was no Ishmael. I couldn’t take my hypos with me aboard some whaler. I had to lie abed for a month until my psyche began to knit and mend.

Lincoln would endure bout after bout of the hypos, until a permanent sadness settled onto his sallow face. Billy Herndon described him this way: “He was lean in flesh and ungainly in figure. Aside from the sad, pained look due to habitual melancholy, his face had no characteristic expression.”

This ungainly man soon percolated in my own melancholic imagination. And I realized I had been unjust to Lincoln—he was far from a saint. He had his own quiet power and a voice that was lyrical and dark. According to Edmund Wilson, in Patriotic Gore, Lincoln’s poetry wasn’t revealed only in his letters and speeches and the tall and bawdy tales he loved to tell. “He created himself as a poetic figure, and he thus imposed himself upon the nation.”

The voice “lyrical and dark”—and comic, too—that you create to narrate I Am Abraham is, to me, the distinctly literary achievement of the novel. What were your sources for that voice—or voices, because Lincoln is sometimes hick, sometimes Cicero?

Yes, a multitude of voices, like a great rumble in the head. And how do you capture it, with all its echoes? You have to become Lincoln, like a vampire—or a magician. And I’m neither one nor the other. You listen, and catch a glimmer of his sound. Mostly, you have to invent a kind of music for him, based on your own limitations, your narrow gifts, and what you know about him. Thus, we have the reverberations of the Bible in his letters and speeches and spoken voice, and a whisper of the yarns Lincoln heard as a boy (his Pa was reputed to have been a gifted storyteller). I thought of Mark Twain, as I imagined Lincoln inhabiting the voice Huck Finn might have had as an adult.

In a gorgeously crafted introduction to The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, Lionel Trilling writes about the music of Huck’s voice, which revels in the dread and deep truth of the Mississippi, but also has another kind of power—“the truth of moral passion [that] deals directly with the virtue and depravity of man’s heart.” Lincoln embodied much of the same moral passion. We deify him now. Yet his own Party wanted to get rid of him in 1864 and nominate Grant. Lincoln prevailed, wearing his green shawl in the White House, and gripped with melancholy, his feet constantly cold, he preserved a nation that had begun to unravel, often holding it together with nothing more than the flat of his hand and his unfaltering sense of human worth.

Speaking of worth—do you think I Am Abraham is your best novel? I haven’t read every one of them, but this one seems like it may be a crowning achievement, if one can speak of “crowning” in the democracy Lincoln loved and preserved.

How can I weigh its worth? I reveled in Lincoln’s music, that’s all. There was a magical presence on the page, that of my editor, Robert Weil, who had me revise every other line, who sought a perfection I did not have. I believe in monstrosities, and I Am Abraham is a monstrosity of sorts, raveling out moment by moment with its contrapuntal songs, as if a band of musicians were at play, all of them with Lincoln’s beard and disturbing grey eyes. If the novel works, it will have its own strange divinity. No one really knows how that ever happens.