“Men think they manifest their greatness,” wrote Tocqueville, “by simplifying the means they use; but it is the purpose of God which is simple; his means are infinitely varied. “ Discuss.

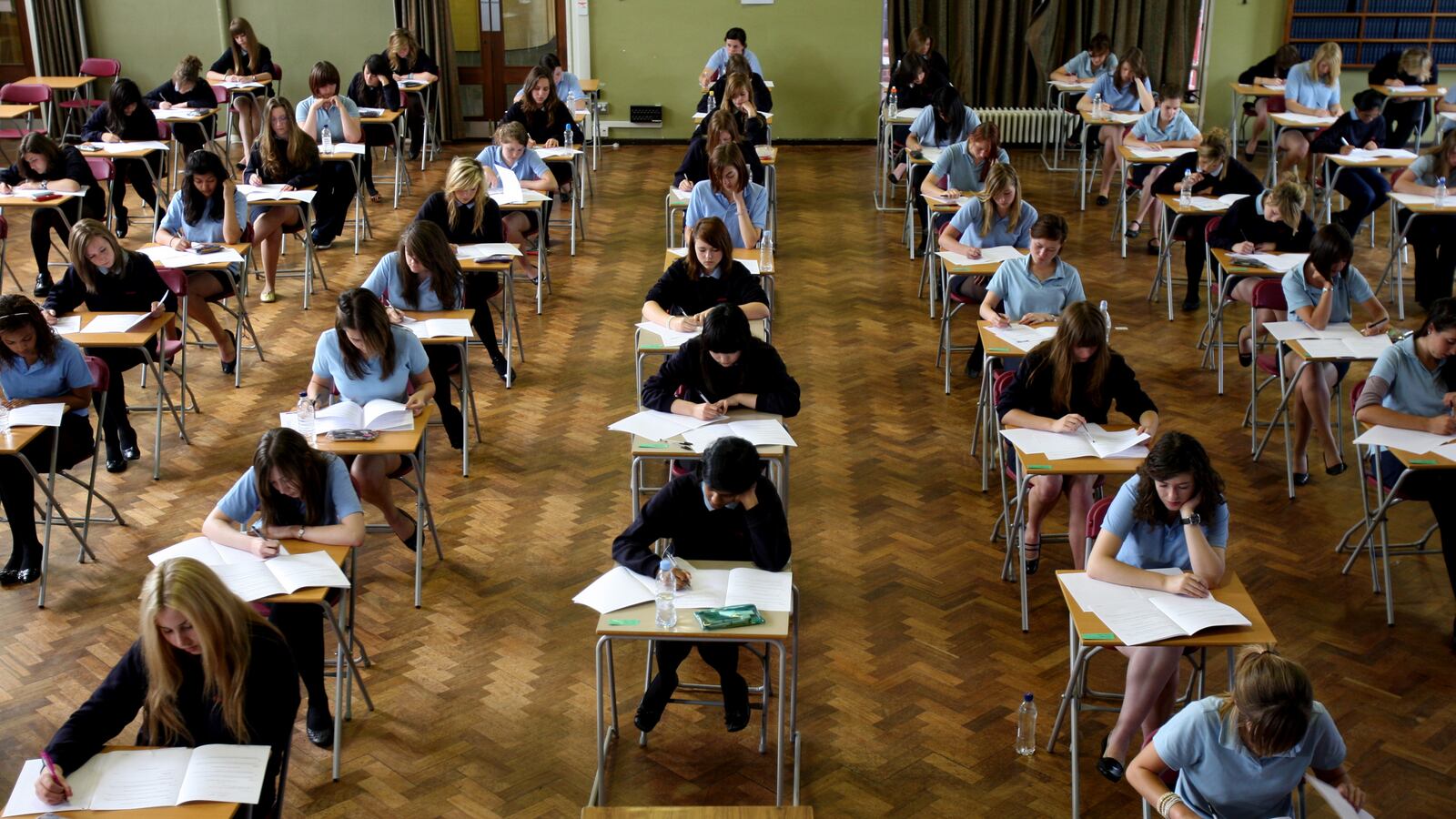

Intimidated? Then you may be delighted to learn that the essay portion of the SAT is now optional. Under pressure along economic, cultural, and political fronts, the College Board—the nonprofit that writes and administers the SAT—has radically revamped the notoriously important exam.

But the test’s decreasing relevance has helped conspire to make the redesign even less effective at identifying what should be a supremely advantageous trait as a college applicant: the love of spontaneously communicating about being human.

Ideally, the SAT wouldn’t involve an essay question at all. Instead, applicants would sit for an oral exam, in the form of an open-ended conversation with a randomly assigned university professor about one or another of life’s biggest and most open-ended questions—the ones that have inspired wonder and reflection among young and old, great geniuses and obscure folk, from the dawn of history to right this minute.

As it happens, the SAT is too important to the College Board and to America’s education machine to score “data” as manifold and diverse as a nation of wonderers coming of age. The test is most often used to quickly and effectively plot you on a graph, the better for admissions officers to rank you in close competition. Killing off the essay requirement reflects that understanding. But it is a concession, as well, that the SAT’s essay section was all but a fraud to begin with.

As The New York Times Magazine revealed, it has long been even easier to “game” the essay section than the multiple-choice portions. SAT critic Les Perelman, MIT’s director of writing, told his SAT students that “details mattered but factual accuracy didn’t. ‘You can tell them the War of 1812 began in 1945,’ he said. He encouraged them to sprinkle in little-used but fancy words like ‘plethora’ or ‘myriad’ and to use two or three preselected quotes from prominent figures like Franklin Delano Roosevelt, regardless of whether they were relevant to the question asked. Fifteen of his pupils scored higher than the 90th percentile on the essay when they retook the exam, he said.”

In that same article, College Board President David Coleman calls the essay “an instrument meant to celebrate writing.” Sadly, Perelman’s investigations laid bare that the SAT essay section takes an immensely cynical approach to testing aliveness of mind. “Big” words, “good” quotes, and “names and dates” function as sloppy factory-line proxies for using language to create and explore a full, engaging relationship with humankind.

Some may say that children of some races, classes, or other identitarian divisions will be at a disadvantage if tested for such expansive and thoughtful capabilities. On the other hand, it’s a “skill set” so integral and natural to human experience that we see it in children all the time, and often take it for granted.

At the same time, it is the hallmark of brilliant people whatever their civilization, epoch, or area of expertise. Even among towering intellects, of course, everyone can’t be a Montaigne; then again, which of them has not weighed in meaningfully on questions of ultimate human significance?

Shying away from pregnant questions like these, the College Board has cast aside the mandatory essay as part of a larger plan to conform the SAT closer to the so-called Common Core guidelines intended to make our educational system even more uniform and our educated minds even more undifferentiated.

We all share a similar level of aliveness, but experience being alive in a myriad of ways. That natural diversification toward a rich human ecology doesn’t just make life more interesting and three-dimensional. It educates our political imagination. Citizens and leaders are welcomed into power based on the love, care, and respect they bring into conversations with one another about each or all of us can live.

If, however, we obsessively reinforce the idea that injustice has imposed different levels of aliveness on different groups of people? If, however, we teach and test so as to standardize the way that we ask and answer what count as important questions, we exaggerate the adverse political effect of the one type of inequality that persists most in a democratic age.

Here’s how. The more a national college exam imposes a uniform framework for competitive ranking, the more is at stake for those at the very top of the socioeconomic pyramid—who often demand, above all, access to political power. In a regime like ours, where elite education is the gatekeeper, competition for that access is, at the upper levels, as finely graded as the Olympic games. The less qualitative that exams like the SAT become, and the more tethered to national standards, the harder children of elites will be compelled to work to best the test, and the more elites will pay to ensure that they do exactly that.

The result? Elites will increasingly feel disgraced if they fall into the “normal” belt of humanity “below” them. Elites will increasingly feel entitled to perpetual political power if they are the select few who have aced out so many of their fellow elites for America’s top power positions (and the world’s). And non-elites with the capacity to draw us fruitfully into the beauty, productivity, and enjoyment of the world will have a harder and harder time “lucking” into leadership.

In thought and in conversation, we sense that this is not the path to greatness. We look with unease on the shadow of wisdom, but refuse to examine it—and our anxiety over all-important tests deepens.