A regime in thrall to Moscow is forced out by a popular uprising; the Kremlin promises not to intervene, and even announces a troop withdrawal. Within days, Russian forces stealthily begin to move in, then pour across the border. A whole swath of territory is reincorporated into what Ronald Reagan called "the evil empire."

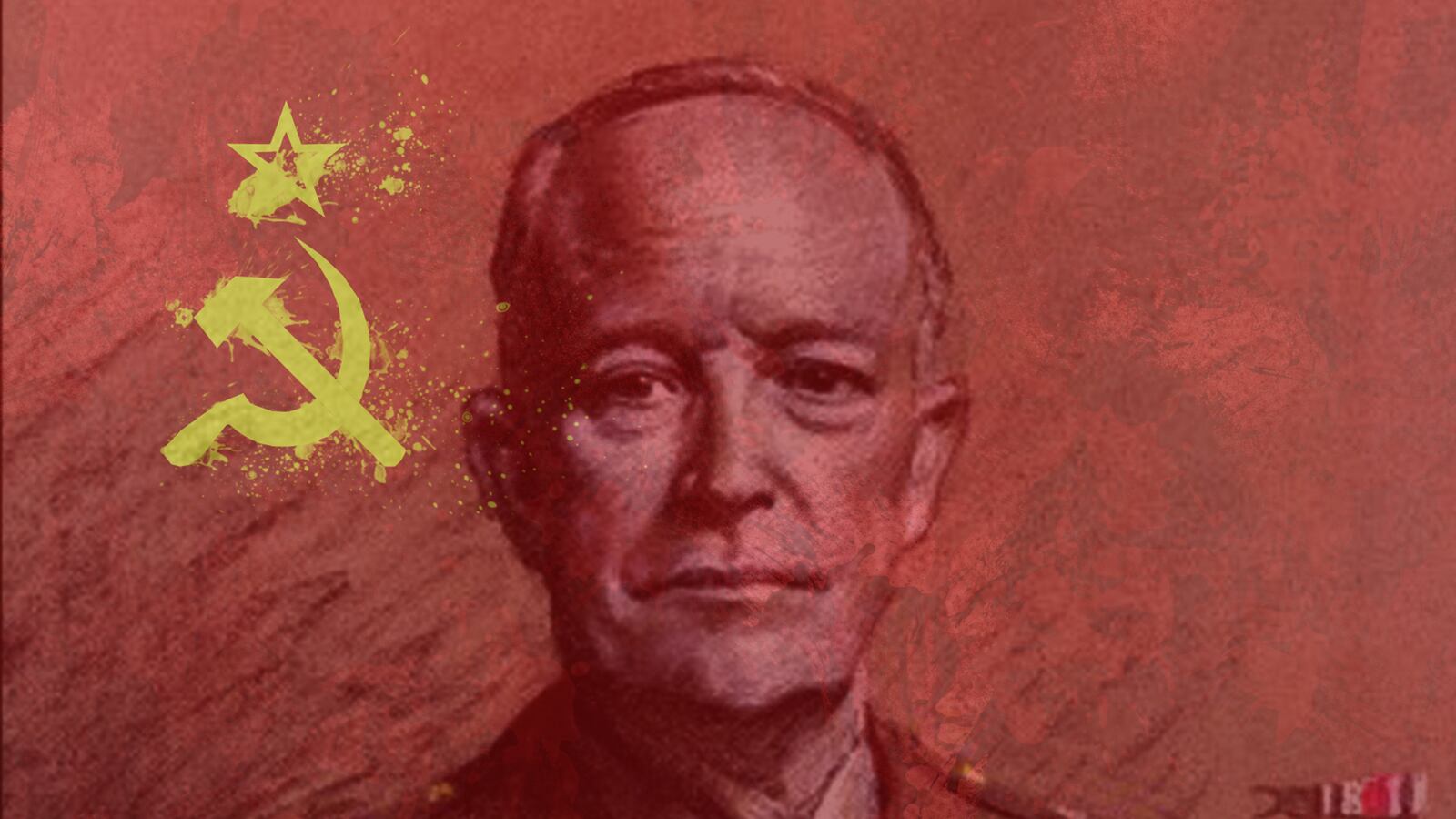

The place was Hungary; the year was 1956; the American president was Dwight Eisenhower, who expressed "shock and dismay" at the Soviet invasion, but refused an armed American response. It was simply too dangerous, too unthinkable, in the atomic age—unless the most vital of U.S. interests were at stake. Even then, Ike once angrily explained to his hawkish advisor Lewis Strauss: "There's just no point in talking about 'winning' a nuclear war."

In fact, the Eisenhower administration had misread and then mismanaged the early and successful steps of the Hungarian revolt, at first denouncing its leader Imre Nagy on Radio Free Europe as a Soviet "Trojan horse," in the phrase of the Eisenhower biographer Peter Lyons. Nagy would subsequently be hanged after a secret, Soviet-dictated trial. And the Kremlin ordered massive forces in as revolutionaries prompted by American "propaganda," Lyons writes, pressured Hungary to the "right"; the new regime had suddenly threatened to withdraw from the Warsaw Pact.

As the uprising was crushed, President Eisenhower even declined to impose sanctions—which would have had far less impact then, when the Soviet Union was economically isolated to a considerable extent. Ironically, at the same time, he did countenance sanctions against Britain and France to compel troop withdrawal from Egypt, which they had invaded to seize control of the Suez Canal. The sanctions continued after a cease-fire; Eisenhower was adamant: They wouldn't be lifted until the invading troops were gone. The British and French, who would soon leave, in the meantime, had to impose oil rationing.

But whatever mistakes his administration may have made, at the heart of the matter, the fundamental question of intervention against the Soviets, Eisenhower was restrained—and eminently right. Barack Obama has followed that path in Ukraine, and so has every other American president confronted with a similar move from Moscow. And while sanctions today may have more bite, even they are unlikely to last. There are too many vital issues on the table—from Iran to Syria to arms control—just as there were when Ike's Vice President Richard Nixon visited Moscow in 1959, and Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev was invited to tour the U.S. a few months later and just 15 months after Imre Nagy was hanged.

It isn't pretty, but it's realpolitik. To Eisenhower, and his successors, the bottom line has been the same: increasing the chance of nuclear conflict is unacceptable when Soviet or Russian misconduct, however shameful or egregious, affects the near periphery of Moscow's influence and the less urgent bounds of America's interests. (As Suez demonstrated, it was a lot easier to be tough on allies than on a potentially mortal adversary.)

Thus Lyndon Johnson, as he reported in his memoirs, decided "there was nothing we could do immediately" about the 1968 Soviet invasion of Czechoslovakia—and the non-immediate response would "be no announcements about [Johnson] visiting the Soviet Union or...nuclear talks." Not long after, Nixon, now president in his own right, reprised the Eisenhower model, opening intense arms control negotiations with the Soviets and making his own historic visit to Moscow.

And what of George W. Bush, who had famously said of Vladimir Putin: "I looked him in the eyes; I found him to be very straightforward and trustworthy…”?

Bush took carefully modulated steps when Putin straightforwardly invaded the nation of Georgia in 2008. He dispatched some ships to the region along with humanitarian aid and, like LBJ, deferred planned discussions on nuclear weaponry.

The playbook is pretty clear. Bush followed it and that was it—despite the provocative comment of his party's presidential nominee John McCain that "we are all Georgians" and McCain's wish that Georgia was a member of NATO, which would have mandated American military action.

To be sure, the world is different than it was in 1956. Russia is not the Soviet Union, but the impulse to empire or at least to dominate its sphere of influence remains—and so does its arsenal of 1,800 operational strategic nuclear weapons. In an interconnected world, denying visas to Russian officials and oligarchs will hurt them—and imposing economic sanctions could damage a "Russian economy…already slumping toward a recession."

But Western European enterprises, and to a lesser extent American ones, have major interests in Russia and Russian trade—and Russian natural gas powers warm much of

the continent from Prague to Berlin and Rome. Moscow can deploy its own sanctions. And again, would sanctions last in the face of other dangers? To put it bluntly, which is more important to our national future: slapping the Kremlin or preventing a nuclear Iran, an outcome which depends on a measure of Russian cooperation?

There is one other difference here that counts, and it doesn't argue for armed force or a new and prolonged Cold War: Crimea, whose official annexation to Russia may now be inexorable, has a population that is nearly 60 percent ethnically Russian, and only 24 percent Ukrainian. Unlike Hungary, what's happening there is not a revolt against Moscow, but a popular movement to return to and ratify Russian rule.

In a sense, the present crisis is the unhappy posthumous gift of Khrushchev, who also brought us the most dangerous confrontation in history: the Cuban missile crisis. To commemorate the 300th anniversary of Crimea "joining" the Russian Empire, Khrushchev issued a decree in 1954 that instantly lifted the peninsula out of the Russian Soviet Republic and "gave" it to the Ukrainian Soviet Republic. The gift was a cynical, symbolic, and contentless gambit in a monolithic USSR. But with the dissolution of the Soviet Union, an independent Ukraine took with it millions of Russians—many of them resentful ever since, many in Crimea now who, as Putin's agents exploited their feelings, were provoked to resistance by the rise of an apparently anti-Russian central government in Kiev. There are Crimeans who won't vote to leave Ukraine, but they are a minority.

None of this—or the presence of the Russia's Black Sea naval base on the peninsula—justifies Putin's breach of international borders and international law. But past aggressions against Hungary, Czechoslovakia, and Georgia were plainly Illegal as well. President Obama, like other presidents before him, has reacted in a proportionate way that recognizes what's possible, what's prudent, and what's essential to advancing larger American purposes and avoiding a great power conflict with unpredictable and even catastrophic consequences.

This hasn't deterred Republicans, who either don't know the history or treat it with the same disdain they have for other stubborn facts, from reverting to their first instinct, to blame Obama first—in this case, for what Russia has done, and then for not doing enough to counter and reverse it.

Florida Sen. Marco Rubio, who at least temporarily derailed his presidential hopes by signing onto rational immigration reform, now hopes to redeem himself on the right with calls "to punish Russia.” This is, he adds, "a critical moment in world history." Compared to what? And what are Rubio's answers? Obama has to "understand... that [the Russians] can't be trusted." Okay—and then what? Throw Russia out of the G-8 and then force Moscow to veto a resolution in the UN Security Council. Well, that will turn things around—and in any event, the president and other Western leaders are already on course to boycott the G-8 meeting in Sochi. What they won't do is permanently exile Russia from a globalized economy—we almost certainly can’t—or trigger a new arms race.

Tennessee Republican Bob Corker asserts that Obama's turn away from air strikes on Syria let Putin see “weakness"—and "these are the consequences." What is the logic here? The United States could have struck Syria with virtual impunity. Would that have led Putin to worry that we would bomb Russian forces moving into Crimea—that Obama would defy the lessons of six decades and assume the Russians would not fire back?

Then there is the Tea Party-primaried Senator from South Carolina, Lindsey Graham, who seems to have a chronic case of Benghazi brain. "It [ the takeover of Crimea] really in many ways... started when our consulate was overrun and our ambassador was killed…" The claim is so far-fetched, so insensitive, so untethered to any sensible analysis that the conservative blogger Michelle Malkin rebuked Graham—and reminded him of Putin's 2008 assault on Georgia.

Riding any anti-Obama hobby horse is endemic to today's GOP. John McCain—Lindsey Graham is his tutee and his mini-me—weighed in with a warning that: "Every moment the United States and our allies fail to respond sends the signal to President Putin that he can be even more aggressive in his military intervention in Ukraine." But questioned by NBC's Andrea Mitchell about what he would do, McCain had to concede: "I do not see a military option and that is tragic.” McCain seems never to have met a war he didn't yearn for America to be involved in. As someone who spent time with him in his 2008 campaign put it, he would have been an impulsive, perilous president.

In contrast, House Speaker John Boehner just grabs at the nearest strawman. He has a solution—“dramatically expedite the approval of U.S. exports of natural gas" to replace Russian supplies in Europe and deprive Putin of earnings "to finance his geopolitical goals." As the Washington Post Wonkblog points out, this wouldn't work without "a natural gas teleporter."

Why? "[N]o matter how fast the administration approves new projects, they would take several years to build”—and the prices might not be competitive with Russian pipelines, which carry their supplies "cheaply" to Europe. Boehner's "idea" looks like a classic instance of passing political gas. The next thing you know, he will suggest that a 51st house vote to repeal Obamacare will deliver a strong message to Vladimir Putin to get out of Crimea.

On Ukraine, Republicans who would attack Obama for anything have offered reactions that range from empty, expedient, and incoherent bellicosity to sheer inanity. And the spasms of Republican recrimination have been profoundly ahistorical. For the better part of the century, American presidents have comprehended that not every injustice can be redressed or redeemed by inviting even greater tragedy. This year, the 100th anniversary of World War I, is a time to remember the words of Barbara Tuchman, who in her book The Guns of August chronicled the onset of that conflict, a conflict no one wanted and where no one foresaw the endless horrors to come. Tuchman wrote: "War is the unfolding of miscalculations."

Not on Ike's watch—or Barack Obama's.