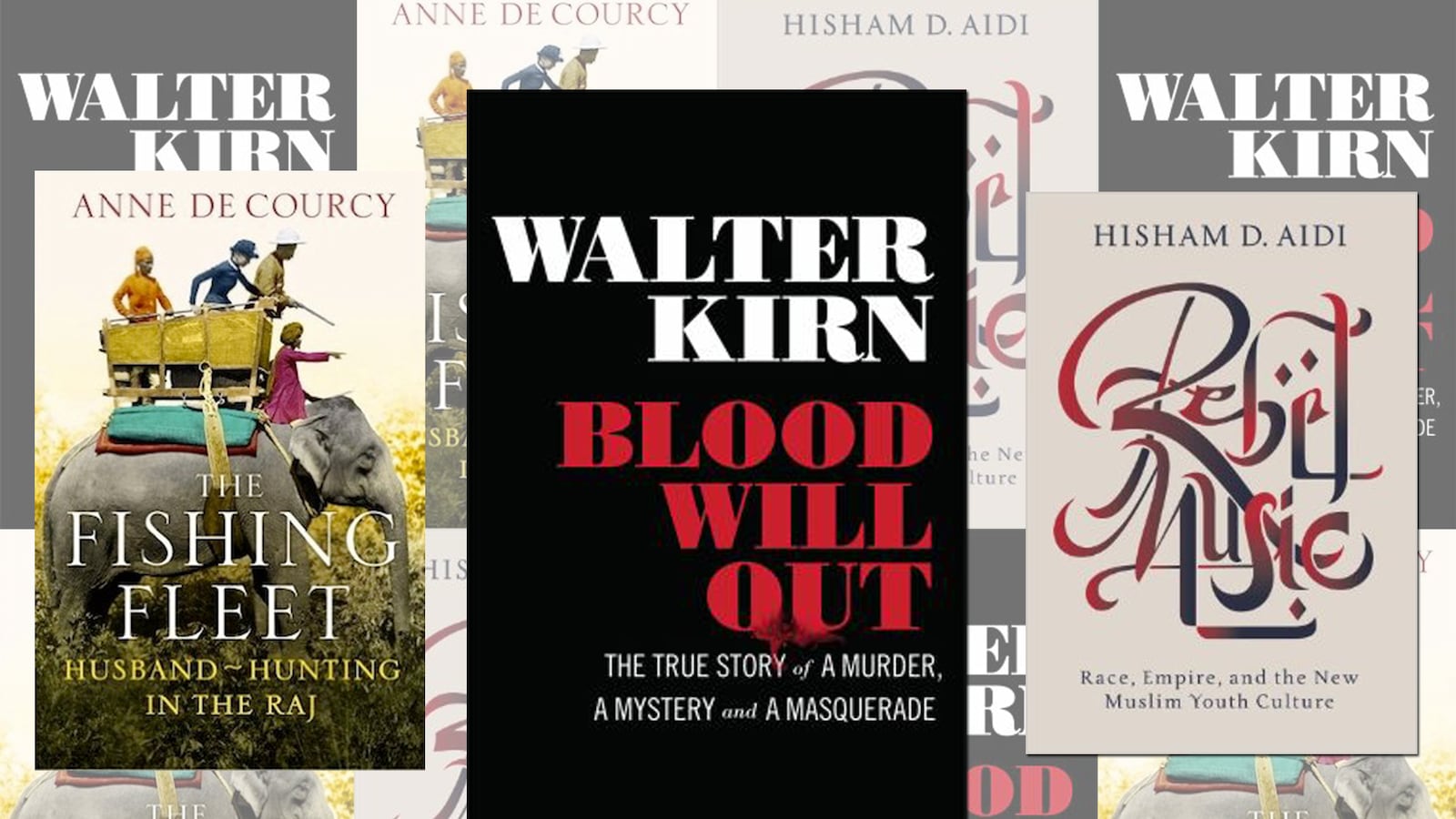

by Walter Kirn

From his earliest school days, Walter Kirn is driven to succeed—to impress his instructors, out-accomplish his peers, earn top grades, and win contests. But midway through his undergraduate education at Princeton, questions of “what else?” catch up with him. What if it’s not enough to be smart and work hard? In Lost in the Meritocracy, Kirn charts how the economics of privilege taunt him at every turn in Princeton. “Even unbidden privileges must be paid for,” he learns. So by the time Kirn meets Clark Rockefeller in the late ‘90s, he thinks he knows a thing or two about the trappings of old money—the eccentricities it fosters, but the ease, too, it allows—having studied the ways of bluebloods.

Only Clark Rockefeller isn’t American royalty, at all. He’s a shape-shifting German immigrant who has made his way across the U.S. one false identity at a time. He’s a hatcher-of-schemes, a flimflam man, a kidnapper and a murderer. On one level, Blood Will Out chronicles Rockefeller’s trial, but the court testimony is really just a backdrop for Kirn’s own meditations about what it means to be the kind of person capable of forming a 15-year friendship with a sociopath.

To Kirn’s credit, Rockefeller was no ordinary conman. There’s a deranged artistry to his inventions. He even manages to convince his high-powered wife (a successful McKinsey executive with degrees from Stanford and Harvard) that he belonged to something called the “Trilateral Commission”—a “shadow global directorate” of sorts. Wading deep into the morass of Rockefeller’s deceptions, in Blood Will Out, Kirn accomplishes the impossible feat of finding a kind of logic—or at least, coherence—in a story of sheer senselessness. The final lesson is one about vanity. But there’s a lesson too, about creative failure. Behind the mask, Rockefeller is a Frankensteined pastiche of a man, a hodge-podge of cultural references and aspirations but nothing more. By the end of the trial, Kirn has settled on a nickname for Rockefeller more fitting than any of the half-dozen aliases he picked for himself: “Hannibal Mitty.” The runner-up? “Gatsby the Ripper.”

by Anne de Courcy

Boarding a boat to Bombay to catch a man might sound like a desperate measure, but in Victorian times, it wasn’t such a far-fetched plan. In 19th- and early 20th-century Britain, because opportunities for women to work were highly limited, husband-hunting was a true survival skill. Only through a stable marriage could a young woman truly ensure that she would have a steady source of income, a place to live, and any kind of social standing.

And at the height of the British Raj, some of the empire’s most eligible young men were stationed in India, where intellectually challenging work and good pay attracted Oxbridge’s finest. But strict British anti-miscegenation laws limited their opportunities for finding a spouse. Enter the Fishing Fleet, boatfuls of young women who came to India to seek their fortune, too. In the early days of British imperialism, “India was seen as a marriage market for girls neither pretty nor rich enough to make at home what was known as ‘a good match,’” but as India’s economic importance to Britain increased, so did the desirability of the white men stationed there.

In her lively history, de Courcy focuses particularly on 20th-century husband hunters, those whose journey was part of “the last flowering of the British Raj” before India’s independence. Their colorful diary entries and letters provide a lens into the courtship rituals and, more broadly, extravagant existence and comically overwrought regal rituals of the ruling class. This is not to say that the living was easy in India; even for the cossetted upper-crust, “the heat, sometimes like a scorching blast form a hot oven, sometimes sticky and damp” (exacerbated by the British conviction in flannel underwear’s medical superiority) was a force to be reckoned with, as were the rains, the insects and the multitude of tropical diseases. But as de Courcy demonstrates, for generations of women, these annoyances were no deterrent for the prospect of a good marriage

by Hisham Aidi

Islam’s scholars and clerics have not always agreed on the place of music in faith. By some strict interpretations, there’s no role for music at all in true Muslim religious life. Yet, as Hisham Aidi makes clear in Rebel Music: Race, Empire, and the New Muslim Youth Culture, music and Islam have a rich, deeply entwined—and even impassioned—historic relationship.

In Rebel Music, Aidi focuses specifically on music as a form of protest or as an expression of unorthodox hybridity among diverse Muslim communities. The most compelling artists noted in Rebel Music take their influence from a mixture of cultures; Aidi’s meandering survey spans multiple continents and even more languages. Take, for example, The Kominas, three Pakistani-American kids who grew up in the 1990s. After learning that the U.S. State Department was “sampling the country’s Sufi heritage for diplomatic purposes,” they began incorporating Sufi music into their rock. Sufi music is put to a slightly different use by French-Congolese rapper Abd-Al Malik, who came to embrace the idea that “Sufi universalism can accommodate the French idea of secular citizenship.” Other adept political messengers (and cultural synthesizers) hail from Brazil, where Malcolm X has inspired a push for social justice, and North Africa, where the sounds of flamenco, rhumba and ragtime mix with Andalusian melodies in the music of Maurice El Medioni and Salim Hilali.

It’s one thing to consider far-away peoples’ cultures, but Islam’s pervasiveness in mainstream American music might come as a surprise to some readers. Aidi’s research notes that Kool and the Gang’s front men were practicing Muslims whose faith shaped their music. One morning, Ronald Bell, aka Khalis Bayyan, read a sura in the Quran that “celebrated life and the creation of man,” and then wrote the track “Celebration.” The songs of the devout, it turns out, take unexpected forms.