There’s an old saying that great movie acting is all about the casting. You can say the same thing for magazine writing as well. Sometimes writer and subject are so suited for each other—like John Schulian and Mike Royko, Mark Jacobson and Harold Conrad or Bud Shrake and East Texas—that the story unfolds like a dream.

Such was the case when Pete Dexter profiled Norman Maclean for Esquire in June 1981. Dexter was already a star as a columnist for the Philadelphia Daily News, but he was different from other big city legends like Royko or Jimmy Breslin. Dexter came at things from the side, never hitting a story square on the head. His columns were hilarious and odd and often disturbing. They more than hinted at his future as a brilliant novelist.

This piece on Maclean was Dexter’s first profile for a national magazine, and it is reprinted here with the author’s permission. Written with care and precision, it is searching and funny, and a fine tribute to a man Dexter deeply admired.

The Old Man and the River By Pete Dexter

Early morning, Seeley Lake, Montana. The sun has touched the lake, but the air is dead still and cooler than the water, and the fog comes off the surface in curtains, hiding some of the Swan Range three miles to the east. And in doing that, it frames the rest. It is the design here, I think, that nothing is taken without compensation, except by men and fires. They leave all the holes.

On the lake a cutthroat trout breaks the surface; pieces of it follow him into the air. He breaks it again, falling back. The water mends itself in circles; the circles disappear. You could never say exactly where, but that’s how things mend; it’s how you get old, too. Not that they are necessarily different things. The place is quiet again. The sun has touched the lake, but the lake still belongs to the night. To the night and to the old man.

He is in the main room of the cabin putting wood on the fire. I hear him humming—a long, flat note, more electric than musical. I think it is a sound he makes without hearing it. He moves from the fireplace to the kitchen wearing a fishing hat, runs lake water out of the spigot into a dented two-quart pan, puts that on the stove to heat. He starts a pot of coffee, leaves it on a counter, and pushes out the door to urinate in the yard. He and his father built the cabin in 1922 as a retreat from whatever civilization there was in Missoula, and they didn’t do it to come down off the mountains and have to look at an indoor toilet.

He comes back in, humming, and surveys the kitchen. He scratches his cheek, remembering where he is. He locates the coffeepot, checks to see what is inside. Part of him is somewhere else. Probably not so much of him that he’d piss in the fireplace and throw the wood out the door, but it isn’t impossible.

The guess is that the part of the old man that’s not in the kitchen is someplace tangent to August of 1949, Mann Gulch, Montana, where thirteen of sixteen smoke jumpers were killed in the first hours of a wildfire that got into the crowns of the trees there. He is in the last chapter of that story now—the jumpers have become his jumpers, he looks at tall trees and imagines fire in their tops, sucking the oxygen out of the air, and feels how helpless a man is in its presence—and while it’s still three hours until he sits down and puts himself back in Mann Gulch to confront it, he is headed there already, feeling his way over what has already been done, measuring what is left.

As far as I know, that’s the only pleasure there is in writing—until something’s finished, anyway. And the old man works carefully and is entitled to his time alone with what he’s done. I stay in bed looking out the window, waiting for him to call me for breakfast.

***

The book was a Christmas present from my brother Tom. I don’t usually read Christmas books. He brought it with him from Chicago, catching a ride east through a blizzard with a girlfriend who wasn’t his girlfriend anymore. I’d met her even when she was his girlfriend, and I owed him for coming. Christmas Eve, she put him out at Exit 4 of the New Jersey Turnpike.

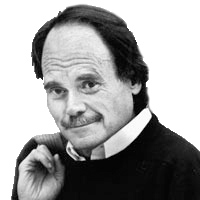

So I read it, I think in late March 1980. I had just taken the Christmas tree out anyway, and when I came back into the house it was lying there in a forty-dollar pile of pine needles. A River Runs Through It, by Norman Maclean. It was a thin book, two long stories divided by a shorter story, on the back a picture of an old man who obviously takes no prisoners, looking at you as if you’d just invented rock ‘n’ roll.

That night I called Tom. “Holy shit,” I said. “Who is this guy?”

“I had him for Shakespeare,” he said.

I said, “The fucker is Shakespeare.”

Don’t tell me literary criticism is a dead art. It turned out Maclean wasn’t Shakespeare, but then Shakespeare wasn’t a forest ranger. Or a fisherman or a logger. He may not even have been a literature teacher at the University of Chicago, but they don’t talk about that there.

Maclean was all of those things, and when he retired from the university at seventy, his two children talked him into writing down some of his stories. A River Runs Through It was published in 1976, when he was seventy-three, and the first 104 pages of that book—the title story—filled holes inside me that had been so long in the making that I’d stopped noticing they were there.

It is a story about Maclean and his brother, Paul, who was beaten to death with a gun butt in 1938. It is about not understanding what you love, about not being able to help. It is the truest story I ever read; it might be the best written. And to this day it won’t leave me alone.

I thought for a while it was the writing that kept bringing it around. That’s the way it comes back to me: I hear the sound of the words, then I see them happen. I spent four hours one afternoon picking out three paragraphs to drop into a column I was writing about the book, and in the end they didn’t translate, because except for the first sentence—“In our family, there was no clear line between religion and fly-fishing”—there isn’t anything in it that doesn’t depend on what comes before it for its meaning.

If that sounds more like building a house than like building a story, it’s not an accident. Maclean knows what it is to work with his hands, and for him there is as much art in a cabin as there is in a story, as long as it’s as well done. And there are all kinds of stories and all kinds of houses, but only the ones you have lived in matter.

***

At seven-thirty, Norman Maclean brings in coffee and orange juice.

Seeley Lake lies in the valley between two mountain ranges: the Swan to the east, the Mission to the west. The cabin is on the west side of the lake, built of lodgepole pine on land leased from the U.S. Forest Service in one of the best stands of western larch left in the world. Some of the trees are seven hundred years old. A hundred yards south is a public camping area.

On warm weekends during the summer, the camp fills up with “outsiders”—people from places like Helena and Great Falls. Maclean also calls them “the marijuana set.” Sometimes they steal his firewood. “They defile this place. They come in on motorcycles, they yell all weekend, and Sunday night they’ll steal your dog on the way home.”

After August, though, they don’t come back. The ski boats disappear from the lake, the fish come back to the surface in the morning and at dusk. “The bears and I take over after Labor Day,” he says. “Two of them sat right there on the steps last year. I’d come home from fishing or a walk, and they’d be there waiting for me. I’d honk the car horn, wave my hat…” He touches his head, then frowns. “Did you see my hat?”

We are standing outside. I don’t see his hat; on the other hand, I don’t see bears. It turns out they are hard cases and won’t move for hats anyway. “It’s no good for anybody when bears lose their natural fear of men,” he says. There is a lot of truth in that—it is two days since a couple of college kids were killed by a bear north of here—but there is a scolding in what he says, and I don’t think he would say it except for the lost hat.

Out on the lake a boat bangs past, then a line, a skier. The skier falls. Maclean watches the small explosion in the water—a leg, a ski, a life jacket. “Sink,” he says.

For six weeks after Labor Day, Norman Maclean has the west side of the lake to himself. It snows for about ten days in early September, then turns warm. Every morning he writes, from nine or nine-thirty to noon. He sits at a small red table in the middle of his living room—the same table where he’s just eaten breakfast—and squeezes out three or four hundred words from Mann Gulch, in longhand. Words that will be rewritten three or four times.

He will not work on the porch; there is too much out there to watch, and he will not indulge himself that there are mornings he can’t write. He doesn’t have the time.

“When it’s good,” he says, “I see my life coming together in paragraphs.”

After the writing he takes a bath in the lake. If it’s snowing, he gets cold. In the afternoon he walks or fishes, visiting the lakes and rivers and mountains of his stories, crossing tracks half a century old.

In October it snows again, this time with nothing behind it but more snow, and the old man closes up the cabin and drives back to Chicago to wait out Montana’s winter.

“Right here, this was the place,” he said. We were standing beneath a pine tree, looking a mile across Holland Lake to the place where runoff from one of the Swan Mountains empties into it. A waterfall. “I used to come here with Jessie, before I married her, and tell her what a hell of a fellow I was going to turn out to be. I don’t know if she believed that bullshit, but she used to get a far-off look in her eyes…

“Her family was Catholic, but they all jumped the fence somewhere along the line. She was from Wolf Creek, population one hundred eleven, and my father married us in Helena. And that woman kept me in place.

“I used to mourn the loss of my youth. I started when I was about twenty, and one day she said, ‘I knew you when you were young, Norman, and you were a goddamn mess.’

“Eighteen years before she died they told her it was hopeless. Emphysema. She wouldn’t leave the cigarettes alone. The last years, she lived with an oxygen tank, but she never whined, I never heard her cry. She died in December 1968, in Chicago, and I thought I died with her.”

***

It is my second day at Seeley Lake. Norman has shown me the Pyramid Mountain Lumber Company. Now he wants to show me the nurse. “You’re going to love her,” he says. “A big, tough talker from Butte. She came here because we had no doctor—they’re all in the cities doing research, where the money is. So I went over to see what this nurse was like. She was in another room with a patient.

“I sat down outside and the first thing I heard was, ‘Open your mouth wider, you sonofabitch, so I can see how big a pill to throw down there.’ A great woman. She knows where I fish, what medicine I need; she and Bud know where to find me if I don’t come back. We go off boozing a couple of times a summer, go to some fancy restaurant fifty miles away.“

That sounds like a good nurse, all right, but somehow by the time we pack the car—a Thermos of ice water, field glasses, six shots of Ancient Age bourbon in a mason jar, and “Did you see my hat?”—we decide to visit Bud’s place instead. Bud Moore is his friend who at sixty-three still runs thirty miles of traplines up into the mountains, who walked his wife almost to death taking her into the Idaho wilderness for their honeymoon.

The place is twenty-six miles north on blacktop, another three and a half over gravel. The only way in or out after December is by snowmobile or snowshoes. Maclean uses his little car without lugging the engine; he doesn’t have to stop talking to shift. He understands the car, but then, he understands the canned peaches in his refrigerator. He can tell you where in Oregon they come from, how they’re canned, and maybe what is done with the pits. He knows his furniture, each of his trees, every log in his cabin—faults and graces—all on a personal basis. He knows everything he touches. Knowing what has touched him has been harder.

“When I tell you how to pack a mule,” he says, “goddammit, that’s how you pack a mule.” He is talking here about his stories, but the stories are as much a part of Maclean as he is of them, and a man like this doesn’t start writing at seventy to flirt with the truth, or the language. “I got five hundred letters about the book,” he says, “a lot of them from fishermen. There’s no bastards in the world who like to argue more than fishermen, and not one of them corrected me on anything. That is my idea of a good review.

“I knew when I started that it was too late for me to be a writer, that all I could hope to do was write a few things well.” We are bouncing up Bud Moore’s road now. “I assemble pieces of ordinary speech. Every little thing counts. You take the way it comes to you first, with adjectives and adverbs, and cut out all the crap. You use an adjective, it better be a sixty-four-dollar adjective. Turn off the faucet and let them come out a drop at a time.”

It took more than two years to put together the 217 pages that make up A River Runs Through It. “At the end,” he says, “I was almost afraid to sleep, afraid I’d lose the connections as it came together.”

When the book was finished, three New York publishers turned it down as “western.” One of them wrote to point out, “These stories have trees in them.” Finally it was the University of Chicago Press that took the book, the only work of fiction it has ever published.

In 1977 A River Runs Through It was nominated by the Pulitzer Prize fiction jury, but the advisory board decided not to make the award, calling it “a lean year for fiction.”

I know just enough about the Pulitzer people to guess that what happened was that one of them noticed the trees, too. The movie offers came in anyway.

“Now, there,” he says, “is a bunch that eats what they find run over on the road. One studio sent out some soft-talker first to tell me about art and the integrity of what I’d written. Then they sent me a yellow-dog contract saying they could do what they wanted with my stories, that they could publish a book about the movie—about my stories, my brother, the people I loved and love—and choose anybody they wanted to write it. I told them, ‘When we had bastards like you out West, we shot them for coyote bait.’

“So the studio people turned it over to their New York attorneys—that’s as low as it goes, New York lawyers who can’t make it in New York and go to California—and they studied the situation for a year and discovered the book was autobiographical. I’ve got a cardboard box full of letters, and it was eighteen months before anybody read the sonofabitching book.

“Another year passed, and another soft-talker showed up, saying he cared about art. I told him what had happened with the studio, but he was with an independent producer. He said it would be different, and the next thing that came in the mail was the same goddamn yellow-dog contract that no West Virginia coal miner would sign. They said they had to have artistic control. Not with my family, my stories. Nobody else is going to touch them.”

I ask if he ever thinks about what he might have written if he’d started earlier. He shakes his head. “I try to live without regrets. Besides, I think there are probably patterns and designs to our lives. Mostly, of course, it’s fuck-ups, but there are designs too …”

Norman Maclean didn’t go to school until he was ten. The truant officers got him while he was out hunting. His father was an immigrant Scottish Presbyterian minister and had kept his older son at home and educated him himself.

Paul was three years younger and went to school. Mornings the brothers studied, afternoons they went into the woods or fished the Big Blackfoot, a river the family came to look on as its own. The brothers were fighters and fishermen. Paul was a gambler, a drinker, a genius outdoors. He became a reporter for a small newspaper in Helena, and later, when he was killed, it was probably over gambling debts. The men who beat him to death were never caught. Norman was less of a gambler, less of a drinker, less of a genius outdoors, and he went to Dartmouth, where one of his teachers was Robert Frost.

“I don’t think Frost ever read a paper any of us wrote,” he says. “We’d meet once a week around the fireplace in the basement of the chairman of the English department’s house. Frost would just walk back and forth in front of the fireplace and talk and talk and talk. Dramatic monologues. There was a sense of character in everything he said and everything he wrote. I am directly indebted to him. As a writer of prose, my debts are nearly all to poets.”

Maclean graduated from Dartmouth and taught there two years. He came back to Montana and worked for the U.S. Forest Service for another two years. Then he went to the University of Chicago as a graduate assistant, teaching three sessions of English composition.

“The University of Chicago is a tough place. I had to get drunk Friday night so I could spend all weekend in bed, marking papers.” And summers he would come home to Montana, trying somehow to marry the things he found beautiful—the woods and language—and live with them both. He would do that all his life, but his talent was teaching.

“It’s like shooting a scatter-gun, or fishing, or anything else,” Maclean says. “Take a collie out into the field every day of his life, show him a bird and hold his tail straight, he isn’t going to learn to point. And if you don’t have the genes, you can teach until you die and never be better than a C—or a D +…”

Three times Maclean was given the University of Chicago’s award for excellence in undergraduate teaching—an award that traditionally is given only once. There have been honorary degrees from other universities; the last one, from Montana State University at Bozeman, particularly touched him. He is professor emeritus at Chicago, and there is a scholarship in his name, set up by some of his former students. One of those students is Supreme Court Justice John Paul Stevens, who from time to time tells a law-school class that the best way he knows to prepare for the law is to take Shakespeare from Norman Maclean.

“Shakespeare,” Maclean says—“he must have known more about writing than anybody else ever did. Every year I said to myself, ‘You better teach this bastard so you don’t forget what great writing is like.’ I taught him technically, two whole weeks for the first scene from Hamlet. I’d spend the first day on just the line, ‘Who’s there?’”

***

Bud Moore’s house sits on high ground between two ponds, a two-story log cabin he built himself. From the corner of the porch you can see the Swan Mountains; turning your head, you see the Missions. “Look at the notch work,” Maclean says. “Look at the selection of logs. People think log cabins are a lost art, but the truth is they’re better now. The old ones were generally built with the same trees they cleared to build on. You could stand in the middle of the living room and the wind would blow your hat off…”

While he looks for his hat, I read a note on the front door. Bud is in the Bob Marshall Wilderness on the other side of the Swans. He went in with his dogs and his grandson a day or two ago and is not expected back for a week.

“There is a lake on the other side,” he said. We were a mile from the base of one of the Swan Mountains. “Paul and I would climb over in the morning, catch our limit in George Lake, and climb back at night.”

He studied the mountain. A steep, hard climb. Two thirds of the way up, the trees stop growing. “Goddamn, I wish I were good enough to do that again.” The name of a lady we both know somehow got into it then. “Of course I would follow her up there,” he said. “Who would mind breaking a leg like that?”

Maclean walks over to the tent where Bud Moore lived during the two years he was building the cabin. He shows me where a grizzly was shot trying to get in. “That bear ran half a mile after the bullet passed through his heart,” he says. “After he was dead, that’s how much hate he had, a half mile …You can feel that sometimes in a rainbow [trout] too…”

He heads downhill through some woods, tripping now and then on fallen trees. He doesn’t slow down. “Being old isn’t great,” he says, “but you can’t kick when most of your colleagues are on the other side of the ground.”

On the way down he identifies trees by which needles are best to sleep on: Balsam fir is good. Spruce, you might as well sleep standing up. He points out the different wild flowers. “There’s Indian paintbrush… there’s fireweed… there’s bear shit, over near that aspen tree …”

Bear shit strikes me as a colorful western name for a wild flower: I can picture little bunches of it growing here and there up to a tree with a beehive. But it turns out bear shit is bear shit, even in Montana. I ask, “I don’t suppose you can tell which way the bear was going?” but the old man is already moving ahead, humming. We come to a clearing, the site of a small abandoned sawmill. It is where the grizzly ran out of hate. We stand there a moment admiring the spot.

On the way back we stop at a fork of the Swan River, which is the river he fishes when he isn’t fishing Blackfoot. It is more peaceful than the Blackfoot and runs in sight of the mountain peaks where there is always snow.

The Blackfoot is wider and faster and unforgiving, its view is largely a canyon, and the fish he catches there, sometimes he can feel them hate. The Blackfoot is where he crosses time.

Now nearly all those I loved and did not understand when I was young are dead, but I still reach out to them.Of course, now I am too old to be much of a fisherman, and now of course I usually fish the big waters alone, although some friends think I shouldn’t. Like many fly fisherman in western Montana, where the summer days are almost Arctic in length, I often do not start fishing until the cool of the evening. Then in the Arctic half-light of the canyon, all existence fades to a being with my soul and memories and the sounds of the Big Blackfoot River and a four-count rhythm and the hope that a fish will rise.Eventually, all things merge into one, and a river runs through it. The river was cut by the world’s great flood and runs over rocks from the basement of time. On some of the rocks are timeless raindrops. Under the rocks are the words, and some of the words are theirs.I am haunted by waters.—A River Runs Through It

It was the Swan, though, where Bud Moore found him last summer. Lying out on some rocks, not knowing what had happened to him.

Back at the cabin we sit together on a log near the porch and drink bourbon and ice water out of the Thermos cap. I ask about it. “I don’t know what happened,” he says.

“I was fishing, I must have slipped.” He isn’t asking for help.

I hand him the Thermos lid; we drink liquor and look at Bud Moore’s place. He smiles at the electrical wires leading in. “She’ll have him putting in a toilet next,” he says.

From the log I can see the tops of the Mission Range. The old man has been there and left his tracks in everlasting snow. It is coming together now, mending, he sees it in paragraphs, is almost afraid to sleep for losing the connections.

He asks for no help.

He knows that when the time comes there are friends who will know where to look. “Come back,” he says. “We’ll go fishing.”

When I look over, his eyes are in the branches of Bud Moore’s tallest trees, imagining a fire in the crowns. He begins to hum.