The bright Afghan sun shone on my walk to work early April 29. I felt a breeze and saw a row of trees covered in white blossoms. The miniature blooms hanging in fist-sized bunches were the first flowers I’d seen since arriving in Afghanistan.

When I entered the building, a sergeant approached me and said, “Command post just called. There’s a ramp ceremony this morning.” Surprised, I paused, and replied, “Okay, we’ll all go.”

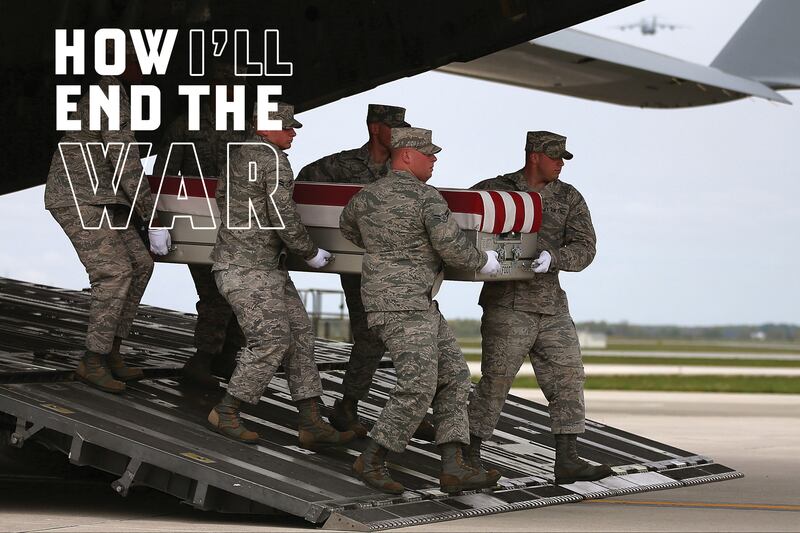

Ramp ceremonies are the transfer of dead service members' bodies onto the aircraft that will take them back to the U.S. or their home country. These observances offer the last chance for units to say goodbye to their friend in the warzone.

We rode in a van out to the ramp where several hundred soldiers stood in formation behind the five-story T-tail of an Air Force C-17. Blackhawk helicopters delivering high-ranking officials offered the only noise. Just outside the aircraft’s darkened interior, near the lowered ramp, the fallen’s unit stood in a tight rectangle. The aircraft dwarfed the thirty or so soldiers.

We lined up to the side of the larger formation. In the distance, hugging a T-wall, two Humvees idled door-to-door with their headlights on. For a moment, the gray plane recalled a thundercloud against the clear blue sky. The color guard’s flags waved. The concrete reflected the heat, and I felt sweat creeping down my forehead. A quintet of brass stood ready under the wing’s shadow. Near the mountains, a Chinook helicopter headed south. Its olive-green fuselage stood out against the snowed peaks.

At the designated moment, a soldier raised his arm, waved, and the ceremony began. Everyone went to attention, and the twin Humvees started rolling toward us. Like soldiers marching shoulder to shoulder, the Humvees drove at the same speed less than a foot apart. They stopped behind the aircraft. We saluted slowly. The band played softly. A detail of about a dozen soldiers marched out to the vehicles. We saluted again. This time we held the salute as young soldiers carefully removed one flag-draped transfer case from each of the Humvees. The red, white, and blue of the flags stood out against the pallbearers’ brown-green uniforms. Led by the color guard, and several chaplains, the detail shuffle-stepped toward the plane and up the ramp. They bore an unimaginable weight. We lowered our salutes. There were no words, and for the bystanders, this concluded the ceremony.

The small unit followed the procession onto the plane, where they likely heard words from their chaplains and commanders, and spent some final moments with their lost brothers. The large formation slowly broke up. Nobody spoke. The band packed up. With lowered heads, people scattered in all directions to continue their day, to continue the war.

Throughout the 10-minute ceremony, I felt the dull nausea of loss. My spine tingled, and I wanted to shed tears. Even though it was right in front of me, the loss seemed seemed so far away. I didn’t even know their names. All I could do was pause, witness, honor the fallen, and think of those close to them.

Less than 24 hours after their death, it was possible that at that very moment, the families of the fallen hadn’t yet received the news.

There were no cameras, not even military photographers. Someone said that photographing these ceremonies is illegal. This policy has flip-flopped through the years. I wondered what the casualty officers would say to loved ones if they asked to see the ceremony.

The Department of Defense highlighted March as the first month without any U.S. combat deaths in Afghanistan. In April, four Americans died—three in combat and one in a “non-combat related incident.”

The next day, I learned about the young men we honored from a military news release:“Sgt. Shawn M. Farrell II, 24, of Accord, New York, died April 28 in Nejrab District, Kapisa province, Afghanistan, of wounds sustained when enemy forces attacked his unit with small arms fire.”

“Pfc. Christian J. Chandler, 20, of Trenton, Texas, died April 28 in Baraki Barak District, Logar province, Afghanistan, when enemy forces attacked his unit with small arms fire.”

I read the names, hometowns, and ages. I saw their pictures online… two good-looking, strong, unsmiling, young men in front of an American flag. I thought of our oldest son serving in the Army in Europe. He just turned twenty-one. I couldn’t fathom the hell their families were experiencing at that moment.

A Stars & Stripes article included a photo of the soldiers arriving at the port mortuary at Dover Air Force Base, Delaware. In the wide shot, the pallbearers are stepping away from the C-17 carrying Sgt. Farrell. The wet ground mirrored the overcast sky and three officiating officers stood saluting in the background. There is something vast about the image, intimate, and haunting.

Perhaps these types of photos should run on the front pages across our country. That way people would at least notice their names.

As I walked back to my room late that night, I passed the row of trees I’d noticed that morning. Strong gusts from a passing thunderstorm had stripped nearly all the flowers from their branches. The white blooms dotted the asphalt and swirled in the breeze under the orange glow of the street lamps.

As spring melts into summer, people are already talking about the potential for the upcoming fighting season.

Nick Willard is the pen name of a military officer currently serving in Afghanistan. He’s previously served in Iraq and Afghanistan. The views expressed here are those of the author and do not reflect the official policy or position of the Department of Defense or United States government.