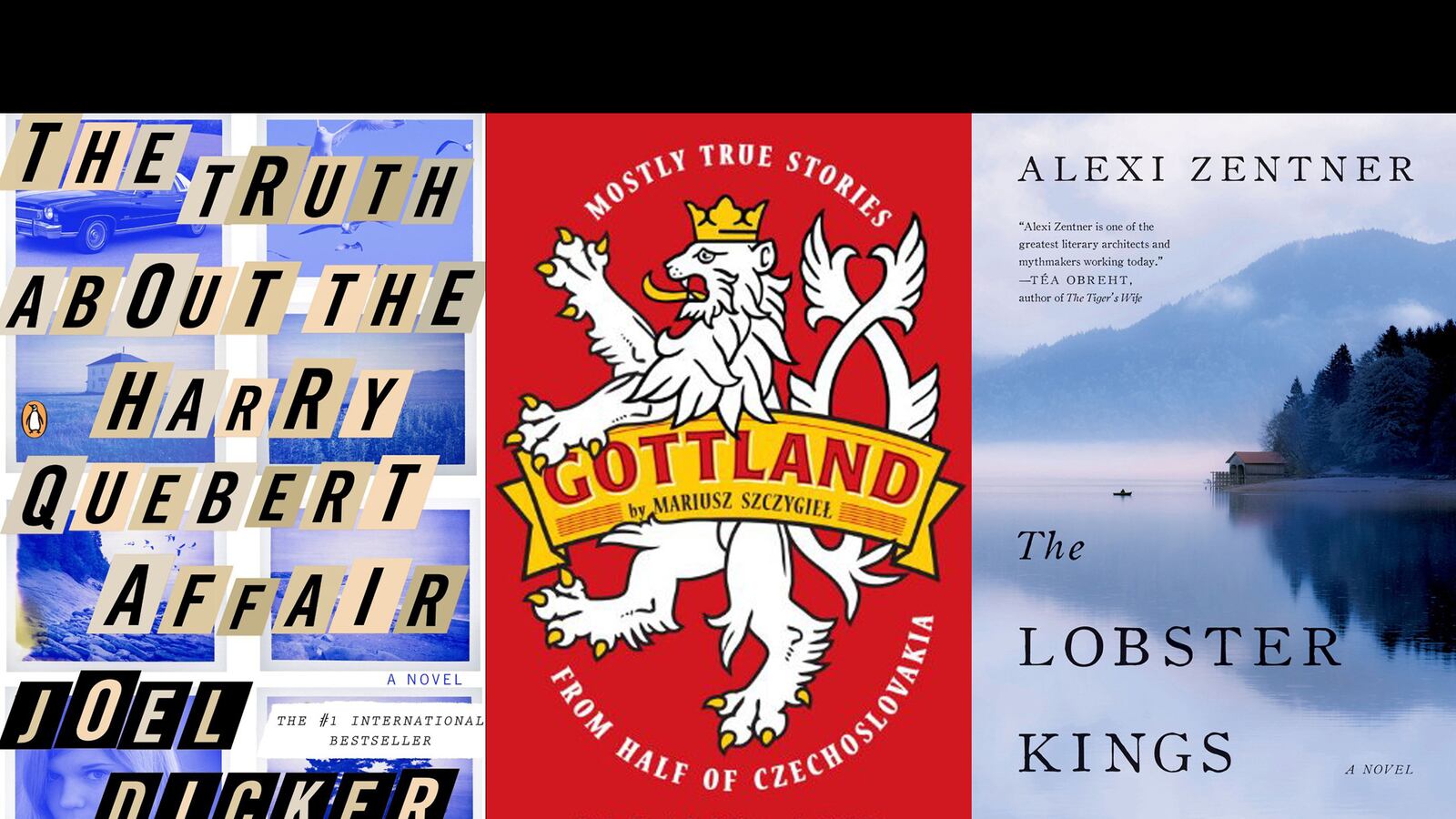

by Alexi Zenter

A modern-day King Lear story finds the three daughters of a powerful lobsterman vying for his affection.

What are we but the sum of the stories we tell ourselves? For Cordelia Kings, the heroine of Alexi Zenter’s Lobster Kings, family lore is destiny. The reign of the Kings family—the “closest thing to royalty on Loosewood Island”—can be traced back nearly 300 years, to when an Irishman named Brumfitt Kings settled on this patch of land off the Maine coast and made a pact with the sea. Generations of Kings, taking after Brumfitt, have fished the island’s waters for lobster, living well off its bounty.

But Brumfitt’s pact came at a price: Each generation of Kings loses a first-born son to the sea. With the early death of her little brother Scotty, teenage Cordelia and her two sisters are left to vie for the affection of their father, Woody Kings. Loyal to her father and bound to the sea, Cordelia wants nothing more than to be acknowledged as truly worth of the Kings name. If this sounds familiar, that’s because The Lobster Kings is a vivid reworking of Shakespeare’s King Lear. Zenter resists using Shakespeare’s plot as the scaffolding for his own, though; the drama of his Kings is instead supported by powerful Scots-Irish myths of the sea.

Zenter’s framework is compelling, but it often feels too heavy-handed. Cooing over baby Scotty, for example, Cordelia’s father Woody Kings declares, “He carries the weight of our history, the lineage of the Kings family.” For her part, Cordelia ruminates endlessly about the family legacy and her place in it. Even when she picks up a German tourist for a brief fling, they lie in bed discussing the symbolic messages layered in Brumfitt Kings’s maritime paintings. Fortunately for the reader, Cordelia is even more headstrong than she is self-obsessed. When meth dealers from neighboring James Harbor begin to encroach on Loosewood, Cordelia’s relentless defense of her birthright as a Kings is downright feminist. As Cordelia learns, the myths that define us are finally meant to be defied, too.

by Mariusz Szczygiel

The Czech Republic’s forgotten history, from a Bata factory’s maniacal leaders to Kafka’s censor-defying niece.

The upheaval of the first and second World Wars so scrambled the Czech Republic’s national narrative and sense of stability that in recent decades, curious western researchers have been apt to find even the simplest inquiries rebuffed by suspicious Czechs. When one inquisitive Kafka scholar arrives in Prague in 1985, for example, she can’t even get a straight answer to the question “Have you ever read Kafka?” Do you have permission?—specifically, “a document proving you have the right to ask that sort of question”—people ask her in response.

To his credit, Mariusz Szczygiel is the sort of reporter who is not easily rebuffed. He even seems to take a special pleasure in following incremental (or false) leads, uncovering buried artifacts from Czech history piece by piece. There is, for example the story of the Bata men, Tomáš and his half-brother Jan, who turned a smaller cobbler’s workshop in Zlín into a vast shoe empire built on idiosyncratic corporate maxims. Or the story of Kafka’s 80-some-year-old niece, Věra S., who, in her prime would loan out her name to colleagues not allowed to publish, but in her old age, is fiercely protective of her privacy. Perhaps the most fascinating story in Gottland, though, is about the herculean erection and then subsequently equally herculean demolishment of a 100-foot-high statue of Stalin in Prague—a project no one, really wants to remember, at all. After the statue—the largest ever monument to Stalin—is gone, “Not a single line about the monument’s destruction appears in the press.”

Although he is first and foremost reporter, the absurd details of the stories in this collection are presented with such wry insouciance that it’s easy to forget (even with the book’s explicit subtitle) that this is a work of non-fiction work. It’d be a work of dark comedy if it weren’t, but as it stands, Szczygiel’s Gottland is something altogether more devastating.

The Truth About the Harry Quebert Affair

by Joel Dicker

A young writer searches for the story that will clear his mentor from accusations of murder in this pulpy European best-seller.

Swiss-born novelist Joel Dicker’s jacket cover bio notes that he spent his childhood summers in New England, but there’s no question that The Quebert Affair is the work of a European through and through. Dicker’s portrayal of American mannerisms, politics, dietary habits, speech, are all charmingly off-kilter, and as such, revealing: This is America, as seen from afar, as in a dream. No wonder it’s already a best seller in Europe.

The novel is narrated by 20-something literary wunderkind Marcus Goldman. At a loss for inspiration for his second novel, Goldman devotes himself instead to investigating the unsolved murder that suddenly, after 35 years, has a new suspect: Goldman’s college professor, writing/life coach, and only real friend, Harry Quebert. Quebert, Goldman quickly discovers, has a troubling secret. While in his thirties, he had an affair with the same 15-year-old girl whose body has recently been discovered buried in his yard. Things are looking pretty bad for Quebert—but Goldman’s faith in his old mentor is unshaken. He’s determined to figure out what really happened to Nola Kellergan.

What ensues is part detective novel, part pulpy romantic tragedy. Quebert’s plot moves with enough sure-footed swiftness that it’s possible to look past Dicker’s artistic limitations—and to ignore how poorly teenage Nola fares in Dicker’s hands. Cast as Quebert’s muse and the darling of Somerset, she’s consigned to be nothing more than a wispy cipher of a woman-child, a blank object of desire with a red dress and mysterious past. But then, she’s a strangely perfect mascot for a book that’s ultimately about empty aspiration and escape.