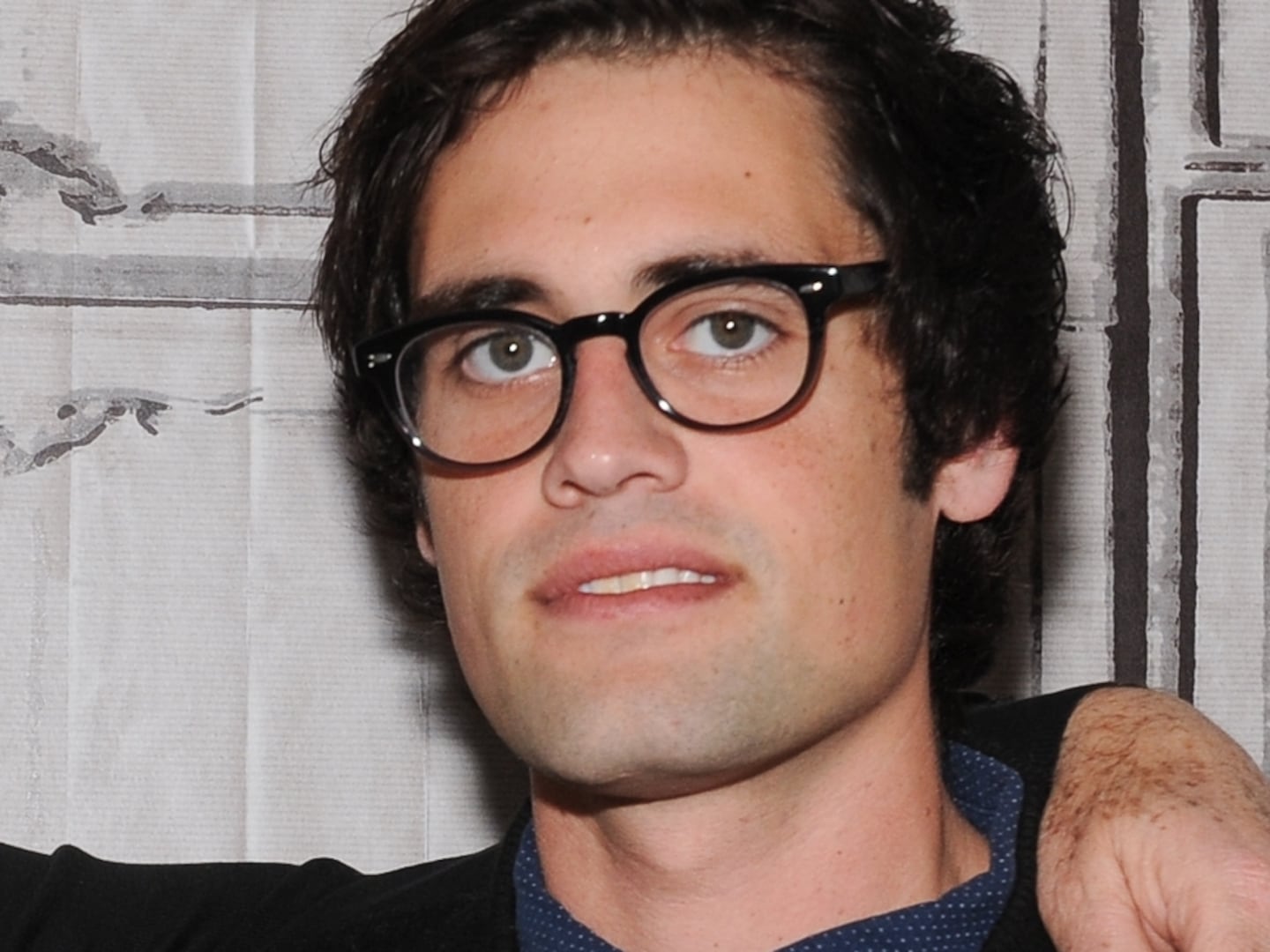

So we’ve learned that Justin Bieber had a penchant for smirkingly throwing the n-word around when he was a teenager. First came a video last week of Bieber at 15 venturing an observation that the motor of a chainsaw sounds like “Run n___ n____ n_____ n_____ n____.” Hot on the heels of his apology for that, the British Sun dug up a video in which Bieber, at 14, briefly parodied his song “One Less Lonely Girl” as “One Less Lonely N----” and joked that he is considering joining the Ku Klux Klan.

None of us were under the impression that Bieber was exactly a United Negro College Fund board member. But we are now supposed to speculate on something grimmer: whether or not he “is a racist” or has a “problem about race.” And really, there is no indication that he has one, at least not one worth wringing our hands over.

First, we should always have been assuming that Bieber flings the n-word around in casual conversation, not surprised to find out he has. Not because he is a “racist,” but because he, a coddled, undereducated and vaguely megalomaniacal celebrity and a boy to boot, is professionally naughty.

People who act up break the rules. And in modern America, the idea that black people can use the n-word and white people can’t is a rule. Specifically, in being a rule that many whites have a hard time making sense of—remember the brouhaha over white Dolphins player Richie Incognito using it as trash talk?—it’s the kind of rule asking to be flouted by little rascals.

That’s easier to understand in terms of the classic four-letter words: We have a rule that certain terms relating to excrement and sex are profane. In an earlier time it was religious oaths that were profane, hence the pox against taking the Lord’s name in vain.

Today, none of those words would qualify as truly taboo to the Martian anthropologist who took a look at how commonly we use those words in pop songs, journalism, and even casual conversation. A world where a hit play can be called “The Motherfucker With the Hat” is one where certain words have lost their sting, even if some outlets refrain from printing the word.

Today, what we consider profane is disparagement of groups, and hence we have only three truly profane words, that we hope our kids will never use even as adults, and that the media “out” someone for uttering roughly once a month. Those three are the f-word referring to gay men, the c-word referring to a female body part, and of course, the n-word. And that means these are the words a modern rascal uses to make us jump.

So, almost 50 years ago, an episode of The Dick Van Dyke show had Rob and Laura Petrie horrified that their son Richie had used a “bad word” at school, which the context suggests was the four-letter f-word. But yesterday’s hot is today’s room temperature. Bieber can’t perform his badboy-itude just by saying f**• when nationwide, perfectly respectable people are joyously squawking it into their cellphones three or four times a minute. Bieber will push the envelope with the profanity of his times.

The same goes for the Klan comment—he was saying exactly what he knew he wasn’t supposed to say. The sad truth is that condemning a word or attitude as profane cannot render it nonexistent: rather, it will live on, vigorously, as what naughty ones pop off with to get a response.

The smirk on Bieber’s face in the first video says it all. He’s in the same jerky “you’re not the boss of me” mode that a real Little Rascal like Alfalfa would have taken on by shouting “Hell!” Note: Just as it would not have classified Alfalfa as a Godless heathen to say that, Bieber’s n-word usage doesn’t brand him as a bigot.

Linguists put it this way. There are times when a person’s utterance is a matter of doing something—performative—rather than expressing something. Think of “How are you?” where you are not genuinely interested in the person’s welfare, but simply performing an acknowledgment of their presence. Bieber was performing: Is that a surprise in any way?

Yet many would object that when it comes to the racial associations of the n-word, even a Bieber is supposed to understand that the taboo is unbreakable. This would bring us back to the idea that he wasn’t just acting up, but acting out some kind of racist animus.

But that analysis neglects the new America, in which Bieber is a sterling example of a white boy who identifies closely enough with black culture that he starts to feel like he has leave to improvise a bit. The rub is when the mimicry gets discomfitingly close—such as using the n-word with what he genuinely senses as an empathetic affection.

Affection, after all, is what the in-group use of the n-word expresses. It means, in this “n-word 2.0” usage, “buddy.” And over the past 20 years, a great many non-black American boys have become culturally blacker than anyone could have imagined before then, in such as way that they have begun adopting, along with so much else, black speech patterns, gestures, and greeting styles. Why wouldn’t they? Boston bomber Dzhokhar Tsarnaev’s black-inflected tweets were a key demonstration of this new reality. No, we’re not past race at all, but these things are real: The weirdness is that it’s happening alongside things like what happened to Trayvon Martin.

Bieber himself has said, “I’m very influenced by black culture, but I don’t think of it as black or white.” He may not, but the rest of us can see an obvious reality in his mentorship by Usher, the “hood” dress style he favors, and even his recent residence in Atlanta, since “ATL” is now considered one of black America’s prime cultural centers. And a guy of Bieber’s age can pull this kind of thing off that “passes” to some extent even among blacks. Even Black Twitterites are given to accepting Bieber as what they openly term a n****.

As such, it’s a fair guess that Bieber—probably even today; some newer video may well pop up—feels like he can use the n-word with a presumption that he, like black men, is using it to mean “buddy.” Told by a black man, the chainsaw joke would go over perfectly well as witty nonsense, for example. A guy like Bieber feels like he’s got the black thing down and is therefore entitled to some leeway. This is how the Dolphins’ Incognito felt in terming himself “honorary black”—and crucially, he was supported in this by some black players.

The n-word now has, therefore, what we could call a “3.0” meaning, wherein non-black young men adopt it as a term of affection modeled on black men’s doing the same. In our times, to indignantly classify every young white boy’s utterance of the n-word as “racism” is behind the times. The word, having jumped the racial fence not once but now twice, is going to challenge us ever more as time passes.

Bieber, then, classifies as a naughty white boy who feels like he’s kind of black himself. Of all the things to call that, “racist” is one of the sloppier choices.