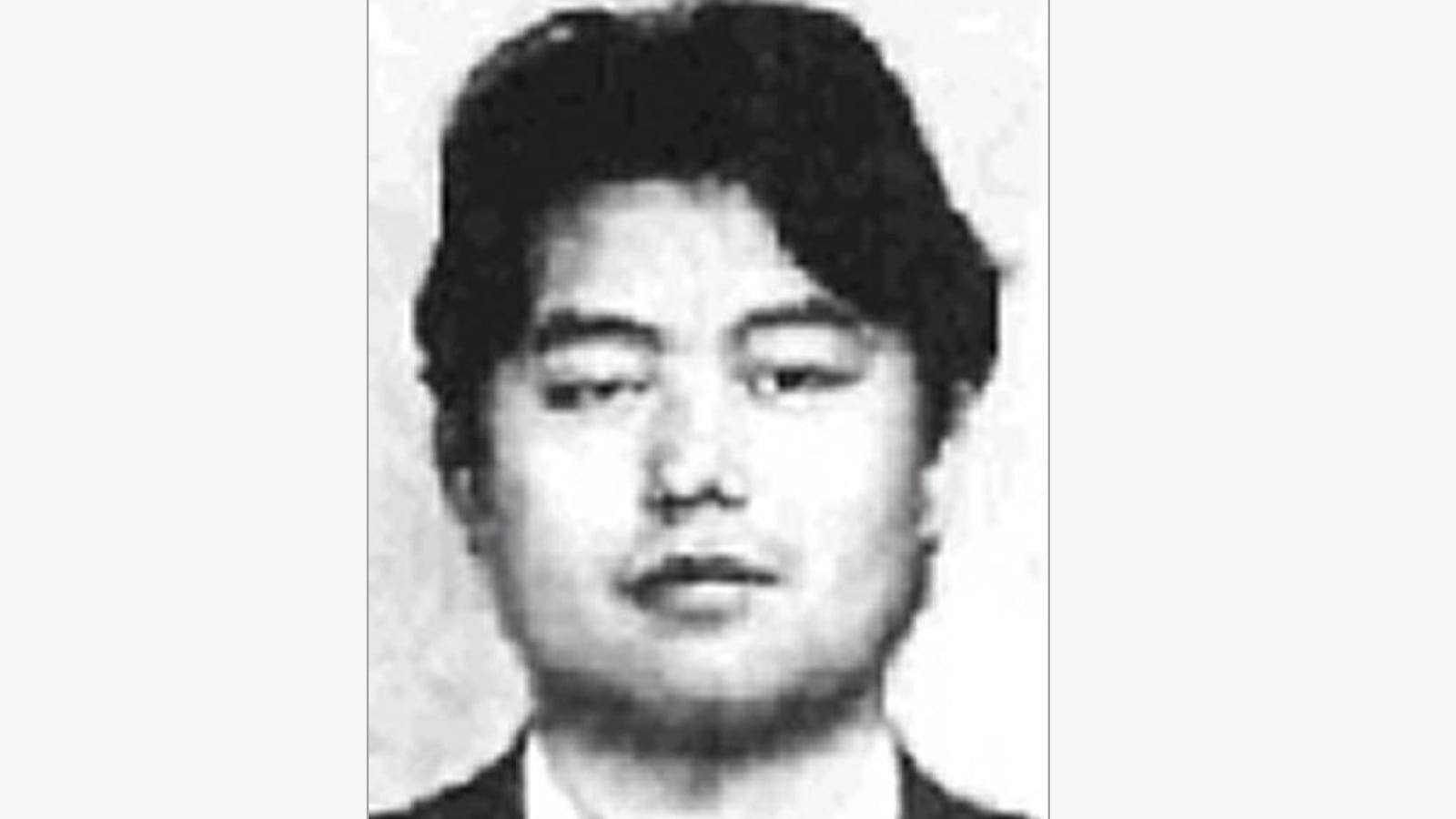

Chinese businessman Li Fangwei, known as “Karl Lee,” is one of the most wanted men on the planet, with a bounty of $5 million on his head.

Li’s alleged offense: flouting the international ban on trading with Iran. But, according to an indictment unsealed in April, Li and his associates were doing business in New York City as recently at 2011—five years after U.S. officials in Beijing had first urged the Chinese government to take action against him, and two years after New York state authorities had indicted him on 119 counts of fraud and deception (PDF) in connection with his Iran dealings.

As international negotiators meet in Geneva on Monday for the next round of talks on the future of Iran’s nuclear program, Li’s career is testimony to the Islamic Republic’s success in building its conventional military power while enduring international sanctions for its nuclear program. The inability to rein him in—or bring him to justice—is a reflection of the enormous complications and conflicting interests that surround Iran’s weapons program.

Li, a 42-year-old metallurgical engineer and entrepreneur in the northeastern Chinese city of Dalian, has been “a principal contributor” to Tehran’s ballistic missile program for years, according to prosecutors. With Li’s assistance, Iran’s Ministry of Defense obtained high-strength metals that can be used to build ballistic missiles and gas centrifuges used in uranium enrichment. Iran’s missile arsenal (shared with Hezbollah in Lebanon) serves as its chief deterrent to oft-threatened attack by Israel or the United States.

Earlier this year Washington adopted Israel’s position that the ongoing nuclear talks should include discussion of Iran’s ballistic missile program, a demand that Iran spurned.

If the current negotiations break down, Israel and its allies in the U.S. Congress are sure to renew the call for a pre-emptive attack on Iran’s nuclear facilities. If that were to happen, Iran might well fire the missiles manufactured with Li’s help at U.S. Navy vessels in the Persian Gulf, Israel’s cities, and its nuclear weapons facility at Dimona.

China has supported sanctions to curb Iran’s nuclear ambitions, while insisting the sanctions be enforced multilaterally. The Chinese government objected to Li’s indictment in April saying it “resolutely opposes” the use of U.S. law to enforce a ban on trading with Iran.

In fact, the State Department has been trying—and failing—to get Beijing to take action against Li since the Bush administration.

In February 2013, Li told a Reuters reporter that he had not violated any laws and said he no longer accepted orders from Iran.

But in the world of Western arms control policymakers, Li remains notorious.

“Not since AQ Khan has a manufacturer of proliferation-sensitive technologies so brazenly and repeatedly sold their goods for use in prohibited programmes despite ongoing attention from national and international authorities,” according to British intelligence analysts Daniel B. Salisbury and Ian J. Steward of the Centre for Science and Security Studies in London in a recent article about Li’s career.

(Abdul Qadeer Khan is the Pakistani nuclear scientist who covertly shared nuclear technology with Iran and North Korea in the 1980s.)

The indictment of Li is “unprecedented for non-proliferation purposes and can be taken as a sign that the US government is still not satisfied with the responses received from the Chinese government," wrote Salisbury and Stewart.

Former U.S. official David Albright and two colleagues called Li a “serial proliferator” in a May 8 analysis (PDF) for the Institute for Science and International Security.

"China’s lack of action over the years to shut down Li’s operations shows that it is willing to tolerate high levels of criminal behavior in violation of UN sanctions on Iran and the international export control regimes to which it belongs,” they wrote.

Not only has Li allegedly violated sanctions on Iran. He did so under the nose of U.S. authorities. He is alleged to have used his front companies to conduct 165 transactions worth $8.5 million in the United States since 2006. While under indictment, he sold one unidentified U.S. firm 20 tons of graphite, according to prosecutors.

Li transferred money in and out of accounts with at least six banks located in New York, including Citibank, Morgan Chase, American Express Bank, Well Fargo, Bank of America, and Bank of China.

Five years ago, when U.S. diplomats complained that that Li had supplied Iran with a machine capable of manufacturing re-entry vehicle shells and solid rocket motor cases, a Chinese Foreign Ministry official spurned the demarche, according to an April 2009 cable published by Wikileaks.

“China’s business is its own business,” the official said, and Li’s firm would be regulated in accordance with China’s “very strict export control laws.”

Li’s dealings with Tehran continued through “an outsized network of front companies,” according to the indictment.

A September 2009 cable from Secretary of State Hillary Clinton blamed “a lack of political will by Chinese authorities.” She said some of them “probably continue to view ballistic missile related transfers as less of a priority than nuclear, chemical, or biological weapon-related transfers.”

After the U.S., China and other world powers imposed stiffer sanctions on Iran in 2009, Li “went underground.” In 2011, he is said to have hosted several Iranians at his factory where he builds machinery to produce aramid fiber, which is used in ballistic missiles and gas centrifuges. Between 2010 and 2013 he “repeatedly traveled” to Iran for “extended periods” to conduct his business, according to the indictment.

He provided world-standard metal products specifically barred by the sanctions regime. In 2012, Li allegedly supplied the Iranians with 20,000 kilos of steel pipe and 1,300 aluminum alloy tubes. According to a September 2009 Wikileaks cable, Li provided tungsten, gyroscopes, and accelerometers to the Amin Industrial Complex, an Iranian weapons manufacturer.

Li’s story “leaves many unanswered questions,” wrote Salisbury and Stewart, whose institute is funded by the British government.

“What has allowed him to continue his activities for so long, whilst leaving such an extensive open-source trail?” they asked. “Perhaps, more importantly in the present, what is the full extent of his network? Are there more companies which Li is involved with, and what other technologies are they involved in manufacturing?”

As the Iranian and international powers seek to draft an agreement by July 20 to limit Iran’s nuclear program and end the sanctions, the saga of Li Fangwei suggests that Iran has well-placed allies in China. Washington wants to put Tehran’s engineering ally out of business, but Beijing doesn’t care to help.