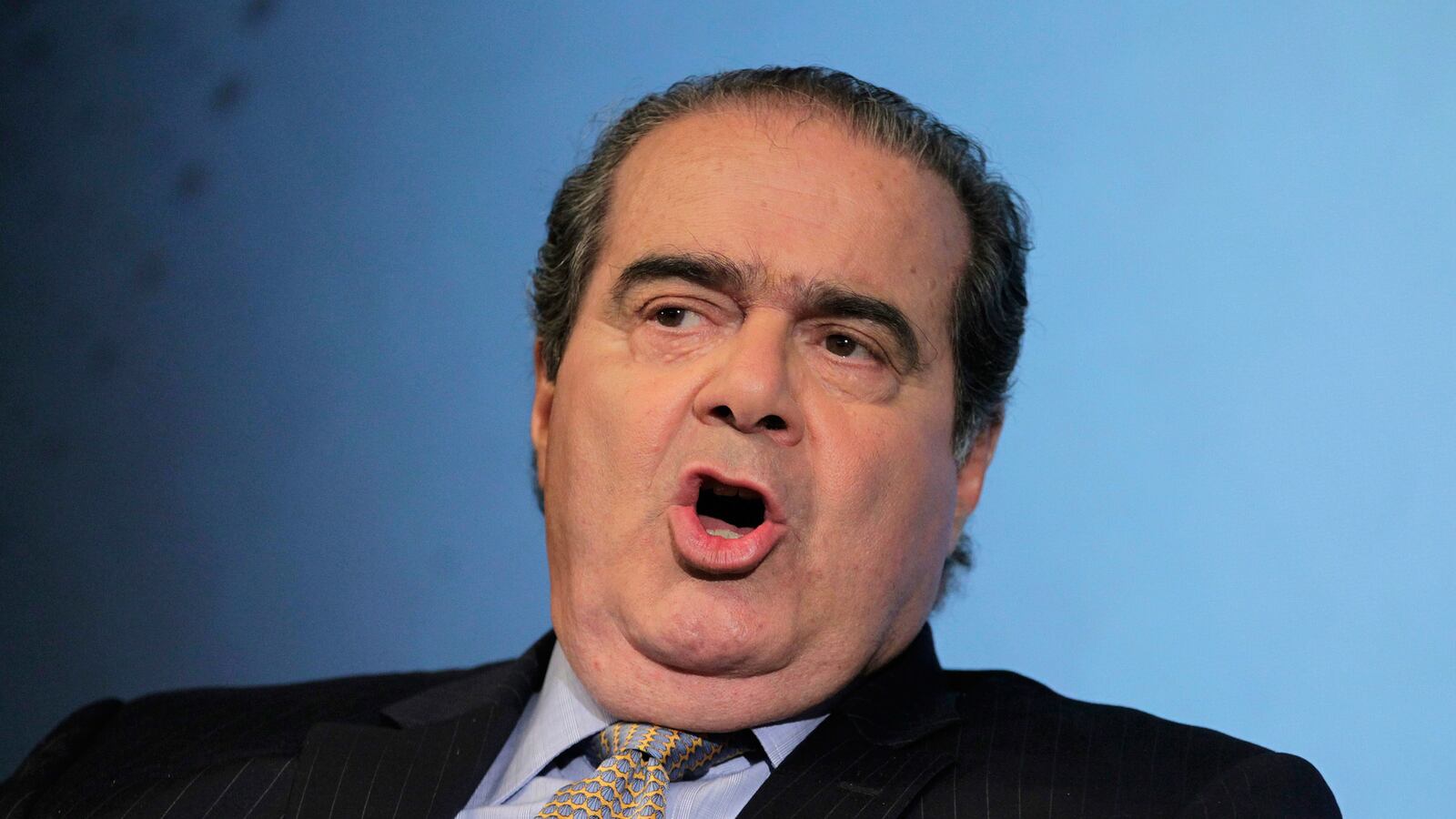

Bruce Allen Murphy is the author of entertaining biographies of Supreme Court Justices Abe Fortas and William Douglas, and he has now written an equally entertaining biography of Justice Antonin Scalia: Scalia: A Court of One. Calling it just a biography would be inaccurate, though. Murphy’s book is biography as criticism, using a justice’s life story as critique rather than just backdrop.

In Scalia’s case, Murphy believes that his subject’s many intellectual and rhetorical gifts have been wasted because of his aggressive and angry style, which is reflected in his behavior inside and outside of the Court. Murphy argues that this style alienated many of Scalia’s fellow justices, and turned him into what the title of the book calls a “Court of One.” Decades from now, though, we will not see Scalia as a lone ranger, but as one of the more influential justices of his time. This is because influence on the Court today increasingly comes not from persuading immovable justices on the Court in the short term, but from changing how we talk about constitutional law outside of the Court in the longer term. On this front, Scalia has excelled, and precisely because of the traits that Murphy finds problematic.

Murphy argues that Scalia’s career has been marked by a “willing[ness] to go to war against his senior colleagues.” When in disagreement, Scalia became known for the “abrasiveness of his attacks against opponents.” He is often referenced as “Nino,” and Murphy reports that professional colleagues came to call the “Ninopath” the path of no compromise that Scalia would pursue. The drafts of his judicial opinions that would reflect this refusal to compromise were called “Ninograms.”

On the Court, particularly in his earlier years, this led many of his fellow justices to react strongly—and negatively—to Justice Scalia. Murphy reports that Justice Harry Blackmun wrote “screams” in the margins of a Ninogram he had received. Chief Justice William H. Rehnquist once wrote Scalia a note to inform Scalia that this style was costing Scalia his influence with moderate Justice Sandra Day O’Connor: “Nino, you’re pissing off Sandra … Stop it!” The Ninopath was also pursued, according to Murphy, in the Justice’s many and notable public appearances. In the past few years, for instance, Scalia has come to call judges who pursue what he considers to be a more activist approach the “Mullahs of the West.”

Murphy argues that this approach minimized Scalia’s influence because it made Scalia less effective at persuading his colleagues of the correctness of Scalia’s jurisprudential approach. But the Court that Scalia was nominated to nearly 30 years ago is not the Court it is today, nor are we the country we were then. In that world—and for many years after—it was possible for a justice to persuade his or her colleagues. Many talked about the legendary persuasive abilities of Justice William Brennan, renowned for using his personal charm and political skills to put together a majority of votes for his preferred position.

These days, more of the justices—and certainly many more of the justices that Scalia will serve with in the years to come—arrive at One First Street, N.E. with set opinions on constitutional issues. The presidents who select nominees come from polarized and ideologically homogeneous political parties, and these parties expect a strong supporter of their cause from judicial nominees, not the moderation of a Sandra Day O’Connor. With the number of interest groups working on judicial nominations growing, and with the greater ease of locating information on the Internet, these constituencies can find a sympathetic nominee whose positions are known well. As a result, as Lawrence Baum and Neal Devins wrote two years ago, “For the first time in more than a century, the ideological positions of the justices … can be identified purely by party affiliation.”

Justices with set opinions cannot be persuaded or dissuaded by personal relationships or tones. A friendship or a smile cannot move longstanding, deeply held beliefs. In other words, justices who were going to vote against Scalia anyway now just do so with a frown instead of a smile because of his abrasive style.

Since O’Connor retired nearly 10 years ago, there has only been one justice on the Court not strongly affiliated with conservatives or liberals: Justice Anthony Kennedy. There have long been rumors that Justice Kennedy can be persuaded by a soft personal touch, a rumor that Murphy repeats. However, there is more systematic empirical evidence that while Kennedy might not always vote with conservatives or always with liberals, he does still vote in a relatively consistent fashion. His ideological variability across a range of issues has caused many to label him the “swing justice.” But it is more often the nature of the constitutional issue rather than the temperament of other justices that influences his vote.

In this polarized era, the legacy of a justice may not be determined by how many colleagues he or she can convince in a particular case, but rather by their longer-term ability to change the conversation about constitutional law among those not wearing robes at One First Street, N.E. With time, this outside game can change what sorts of positions in constitutional law are considered “off the wall” or “on the wall.” It might not win votes today, but it can change the 40-yard lines for a later day. This, in turn, influences how the other branches of government and the American people understand the Constitution, and therefore what sorts of justices can be appointed and confirmed to the Court.

Scalia has been a superstar at this outside game. For audiences outside of the Court, the angry and aggressive approach that Murphy decries might be particularly effective. These audiences are more likely to notice and even appreciate the kinds of opinions that Scalia writes. A public appearance lambasting the “Mullahs of the West” will prompt the kind of discussion that a dry discussion of constitutional interpretation will not.

This aggressive, attention-grabbing style is not without substance, and the many professional faces that Scalia wore before becoming a justice enable him to tailor this aggressive style to multiple constituencies outside of the Court. As a former law professor at several elite law schools, he is adept at discussing high constitutional theory. As a former litigator, he is a master at shaping arguments to persuade. And as one of the initial organizers of the Federalist Society, he is a skilled political tactician.

As a result of these skills, especially when combined with the efforts of other law professors, judges, and even politicians, Scalia has managed to change the way we talk about constitutional law. He has long supported originalism, a complicated term defined by its proponents to mean that the Constitution has a relatively fixed meaning set at the time the Constitution was enacted. Scalia’s efforts have helped persuade many members of the legal profession, political figures, and even the public at large of the merits of this approach.

As a result, our conversation about the Constitution has changed. When Scalia started talking about originalism a generation ago, it was a deeply contested approach. But with time, and in no small part due to his efforts, originalism has become more accepted.

In my constitutional law classes, Scalia is the protagonist in the minds of my students. They look to Chief Justice John Marshall for his opinions making the Supreme Court relevant 200 years ago, but they look to Scalia as the primary jurisprudential figure on the modern Court. When President George W. Bush was campaigning for president in 1999, he cited Scalia and Justice Clarence Thomas as models of the kind of Justice he would aspire to nominate to the Court. In 2008, when the Supreme Court ruled in Heller v. District of Columbia that the Second Amendment protected an individual right to bear arms, it was Scalia who wrote the majority opinion. And even the primary dissenting opinion used a version of originalism.

Indeed, the best measure of the success of Scalia’s outside game might be the fact that his opponents want a Scalia of their own. When President Barack Obama had to nominate justices to the Supreme Court, many liberals said they wanted a “liberal Scalia.”

Whether you like his approach or not, because of these efforts Scalia has an influence that calling him a “Court of One” obscures. In a polarized America and on a polarized Court, the path to influence might not be a smile and a pat on the back but a strong judicial opinion and a formidable appearance on C-SPAN a few months later. As a result, in a generation my students might have no idea who David Souter or John Paul Stevens was, but they will all know who Antonin Scalia was.