The collapse of the Iraqi state over the past two weeks is the result of a carefully planned, controlled demolition. For more than two years, the Islamic State of Iraq and al-Sham (ISIS) has identified the major load-bearing structures that gave the Iraqi government authority, and placed its explosive charges accordingly: it has created sectarian fear with a campaign of car bombs; it has destroyed morale among security forces by assassinating soldiers in their homes; and it has infiltrated peaceful protests, ensuring the government would answer legitimate demands with bullets. By the time ISIS began its assault on Mosul, the government could not claim to defend the rule of law, provide security, or ensure basic personal freedoms. Throughout the Sunni heartland, the government has simply imploded. Iraq's leaders have been expertly played.

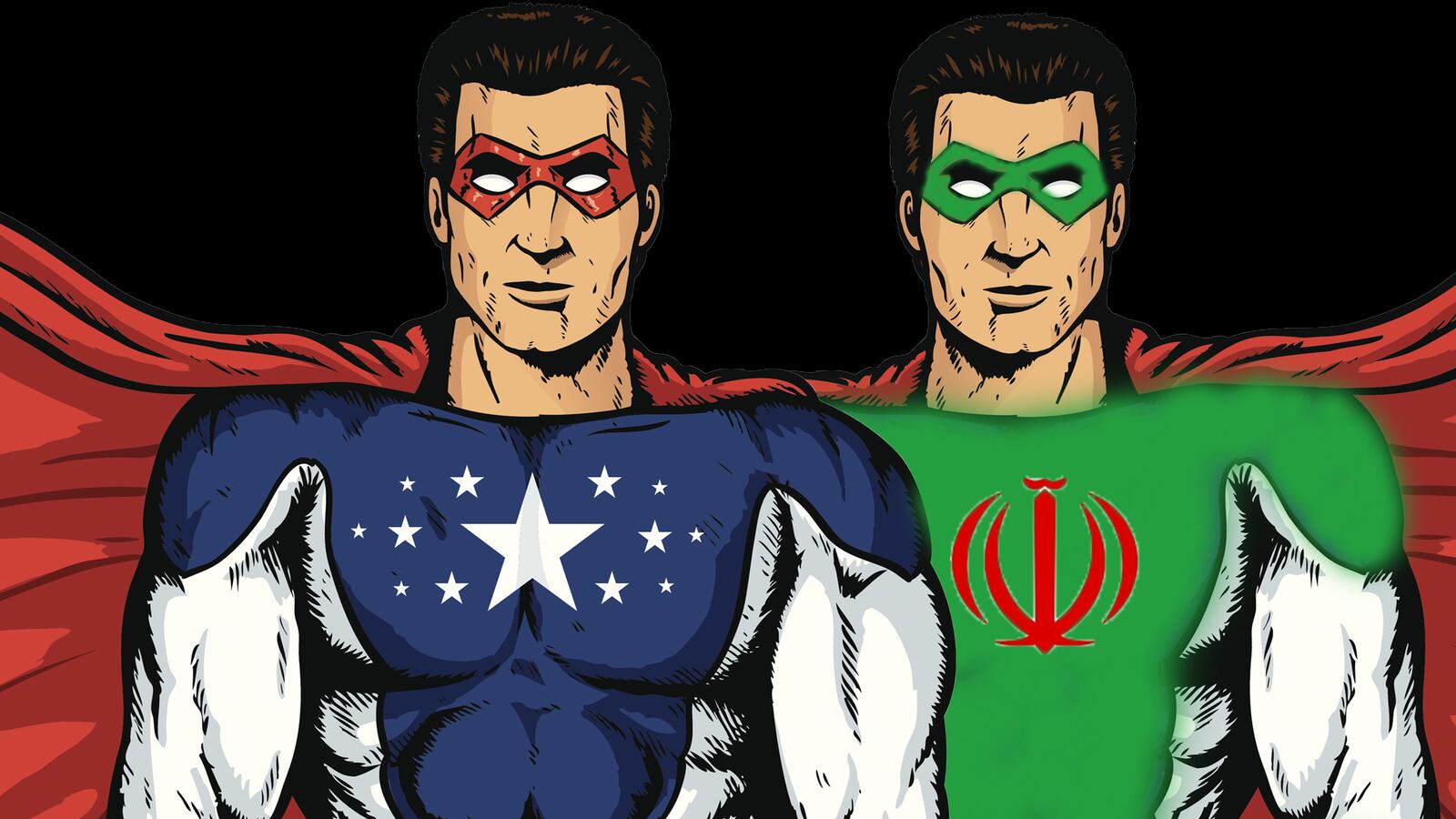

The only way to defeat such a savvy enemy is to exploit its weaknesses. ISIS has plenty. The major problem is that Iraqi leaders are powerless to hit ISIS where it would hurt. In their desperation, they have asked both the U.S. and Iran for help—and that's a good start. Only the U.S. has the precision air power that might immediately turn the tide of battle. Only Iran has the political influence to force political reform in Baghdad. If these two rival powers can work together, there is some thin hope. If not, things are going to get a lot worse.

The central tenet of President Obama's emerging Iraq strategy is that military action won't bring stability unless Iraqi leaders can build a government that all Iraqis might be willing to fight for. "As long as those deep [ethno-sectarian] divisions continue or worsen, it's going to be very hard for an Iraqi central government to direct an Iraqi military to deal with these threats," he said on Thursday. The only problem with Obama's formulation is its implicit assumption that Iraqi leaders can simply choose to make up. In aggregate, they have taken hundreds of millions of dollars from Iran, and some are directly affiliated with Iran-backed militias. As a result, only Iran can push Iraqi leaders toward reconciliation.

Political reform is not just a kumbaya talking point; it's an urgent military priority. One key weakness of ISIS is the extent to which it depends on allies who don't share its ideology. ISIS fighters only number in the thousands; to consolidate gains and hold territory, they need the ongoing cooperation of tribal groups that have been antagonized by the government. In the areas it has captured, ISIS appear to be waging a "hearts and minds" campaign, distributing free fuel and goods plundered from the government. They are trying to turn a jihadi surge into a broader Sunni uprising.

This honeymoon phase won't last long. If ISIS follows the same playbook it has used in Syria, it will soon start imposing its zealous interpretation of Islamic law, which includes punitive amputations and crucifixions of alleged apostates. Such brutality will likely inspire fear and obedience among the overwhelmingly moderate Sunnis of Iraq, but not enthusiasm. And that presents a major opening for the Iraqi government. If a statesmanlike prime minister can credibly offer Sunnis a better deal than ISIS, he might be able to convince them—town by town, tribe by tribe—to stand against the extremists.

Maliki's major missteps have been well documented. The practical question going forward is whether he can inspire faith among moderate Sunnis. But that man is not Maliki. Iraq's minority communities simply do not trust Maliki: there is no political deal he can offer, even if he wanted to, because he has already broken too many big promises.

Obama doesn't want to sound too much like a western imperialist, so he didn't say it directly, but his public critique of Maliki on Thursday, if oblique, was also damning. "We've seen over the last two years... the sense among Sunnis that their interests were not being served," Obama said. "The government in Baghdad has not sufficiently reached out to some of the tribes and been able to bring them into a process that, you know, gives them a sense of being part of a unity government or a single nation-state."

Maliki won a second term as prime minister, in 2010, by negotiating a power-sharing deal with rival parties. Among other things, the agreement would have provided some oversight of Maliki's command of the security forces. It also called for the establishment of laws and institutions that might protect minorities against the tyranny of the majority. These reforms were mostly designed to reassure Sunnis and Kurds that Maliki would not become an autocrat. However, because so much power had already been concentrated in the executive branch, Maliki got to decide the amount of power he was willing to concede—and as it turned out, that amount was zero. Of all the major initiatives outlined in 2010, Maliki has not honored any of them.

Luckily, the stage is already set for political change in Baghdad. Iraqis just held elections on April 30, and, although Maliki was the top vote-getter, many more people voted against him. Normally, Iraqi leaders would now be entering a long phase of coalition-building in which one of the major complications is finding a government that's acceptable to both Washington and Tehran. A direct dialogue between those two power brokers could speed things up considerably.

Currently, though, the U.S. and Iran don't seem to be pushing in the same direction. American diplomats have reportedly explored the prospect of replacing Maliki in meetings this week with Sunni leaders and Shia opportunists like Ahmed Chalabi. But faced with the overtly sectarian threat posed by ISIS, Iraqi Shia parties have mostly rallied behind Maliki. From their perspective, as long as ISIS sits on Baghdad's doorstep, political change can wait.

One practical consideration is that Maliki has aggregated so much direct control over his most competent military units that replacing him would disrupt the chain of command. The state institutions simply aren't strong enough for a smooth transition of power: in a country where the prime minister often literally issues orders to generals via text message, it's not just a matter of Maliki handing over his cell phones.

Given all of this, Iran is apparently disinclined to foment a political rebellion against Maliki among the Shia. Obama seems keenly aware of this dynamic. "Iran can play a constructive role if it is helping to send the same message to the Iraqi government that we're sending, which is that Iraq only holds together if it's inclusive," he said. "If Iran is coming in solely as an armed force on behalf of the Shia and if it is framed in that fashion, then that probably worsens the situation." The question is how to prevent the latter and induce the former.

To this end, U.S. military power could be a decisive lever. For all of the military help Tehran is willing to provide Baghdad, it still cannot match American air power. And only American planes can really exploit another major weakness of ISIS: its ambition to hold territory. For Iraqi and Iranian ground forces, the prospect of a land war looks intimidating because insurgents have accumulated a fleet of armored vehicles and an arsenal of heavy weapons. For an American fighter pilot, however, ISIS convoys and fortifications look like great things to bomb.

Obama has moved an aircraft carrier into the Gulf, increased aerial reconnaissance and intelligence cooperation, and ordered hundreds of special operations troops into the country as nominal advisors. In other words, he is building the support structure necessary to identify targets and conduct air strikes. Yet he has not come close to dropping any bombs, as the Iraqi government has now requested. The quid pro quo is there for everyone to see: the U.S. will take action, and very likely turn the tide of battle, if the politicians can form an inclusive government.

Such an offer should be attractive to Iranian leaders. Keen as they are to defend their Shia brothers in Baghdad, they have an even greater interest in restoring some stability along their western border. Their ground forces would also surely appreciate the air support. By partnering with the U.S., they could potentially achieve all of these goals -- and might even build mutual confidence that would carry over into nuclear negotiations. Yet they're also hesitant to make the first move. "We can think about it if we see America starts confronting the terrorist groups in Iraq or elsewhere," Iranian President Hassan Rouhani said last week.

There are many reasons such cooperation might not work. First, Maliki has a tight grip on power that could hold even under pressure from his two most important allies. Moreover, any truly effective coordination would be politically controversial, logistically problematic, and hard to sustain. Following their brief sojourn during nuclear talks in Vienna, both governments responded to the curious questions of reporters like two kids caught with a pack of smokes, denying they had inhaled.

Awkward as this may be, however, there are no better alternatives. If Obama continues to engage with Iraq at arm's length—mainly through bilateral diplomacy, weapons sales, and a slightly larger training mission—then Iraq's Shia leaders will learn once and for all that only Iran really has their back. Already, thousands of Iranian Revolutionary Guard Corps troops have reportedly entered the country through at least two border crossings, and the shadowy Quds Force controls homegrown Shia militias throughout Iraq. In contrast to the feckless Iraqi commanders who fled Mosul, these Iranian forces are disciplined, motivated, and ruthless. They are also likely to stoke the kind of sectarian mistrust from which ISIS draws its strength.

During last decade’s Iraqi civil war, for example, Iran's proxy militias weren't just attacking U.S. troops and Sunni militants; they were also conducting systematic campaigns of sectarian revenge killing against Sunni non-combatants. Sunni families in historically heterogeneous areas picked up and fled, eager to avoid a power drill to the forehead.

There is every indication that this pattern has begun to repeat itself now. In the months before the fall of Mosul, scores of Sunnis turned up dead in Baghdad, victims of mass executions. Hundreds of families moved out of their homes in Diyala province due to intimidation. The government has been complicit: Iran-backed militias are now reporting to a special division of Maliki's office, and in some cases, they are conducting joint operations with government forces. The abuses have apparently escalated recently. For example, on Tuesday in Baquba, the capital of Diyala, 44 Sunni prisoners were found dead in a government-controlled prison with bullet holes in their heads.

Quds Force leaders might not be ordering these atrocities directly, but they do appear to take a "boys will be boys" attitude toward horrific violence. As long as they do, it's difficult to imagine that any Sunni leader will be eager to collaborate with a government that also partners with sectarian killers.

There's no guarantee the U.S. can wield enough leverage to affect Iran's behavior, or that Iran exerts enough control over the militias to calm the sectarian frenzy. For this reason, Obama appears disinclined to order air strikes unless the conditions exist for political progress. The nightmare scenario is that the U.S. could find itself bombing Sunni-majority cities while Shia militias run rampant through Baghdad. The war would become increasingly sectarian, with America taking sides. Any military victory would be fleeting. ISIS would no longer need to produce propaganda videos, because the atrocities reported on CNN would be enough to radicalize the next generation of jihadis.

If the stakes weren't so high, there would be something comical in watching American and Iranian leaders slowly come to realize their shared interests and complementary strengths in Iraq—like middle schoolers with a mutual crush eyeing each other from across the dance floor. On Monday, they made their first awkward attempt to hold hands, when Deputy Secretary of State Bill Burns talked with his Iranian counterparts about Iraq on the sidelines of nuclear negotiations in Vienna. Let's hope they dispense with the slow courtship and start to dance.

##

The managing editor of Iraq Oil Report, Ben Van Heuvelen has reported on Iraq since 2009.