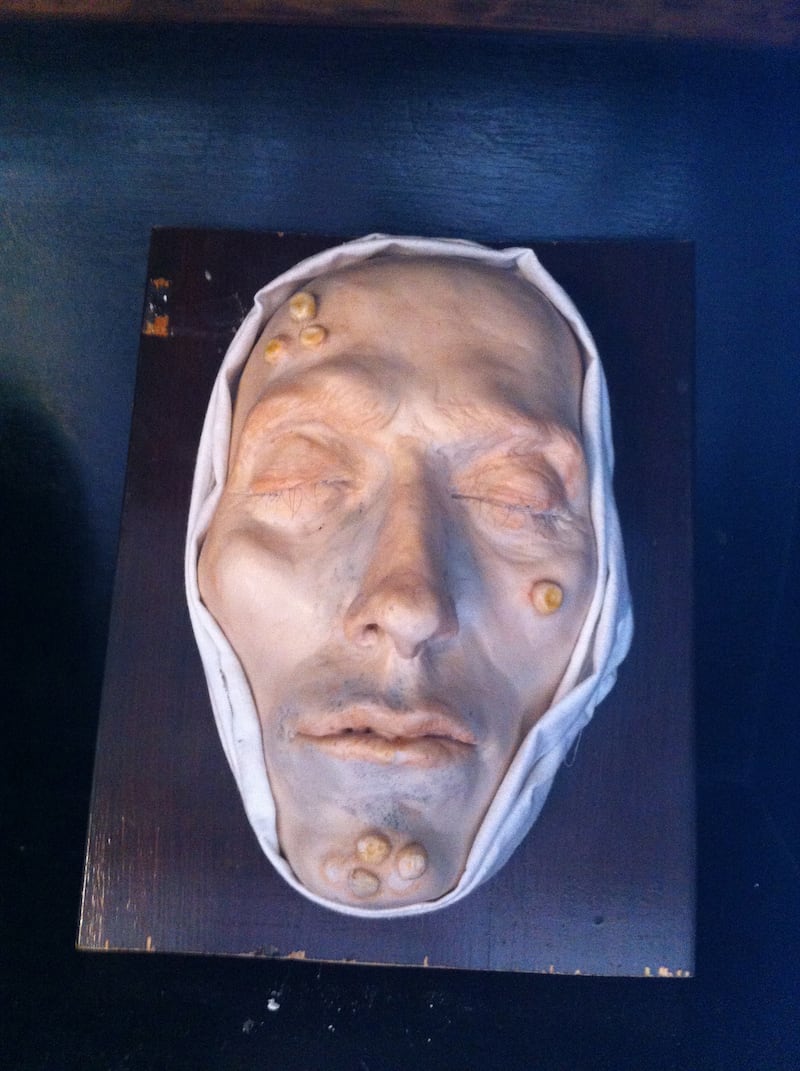

She’s known as the Mona Lisa of death masks.

In the 1880s, the body of an unknown young woman was found floating in the Paris waterway. Her face was cast into a plaster mold, preserving her shy smile for posterity. This was a traditional practice of those days, but the peaceful look on her resting features so captivated the French public that her death mask was mass-produced and soon hung in well-furnished parlors across the country.

And now one adorns a corner wall in Brooklyn. At the new Morbid Anatomy Museum and Library, a mold of the young woman, dubbed L’Inconnue de la Seine (“The Unknown Woman of the Seine”), shares display space with spirit photography, elaborate wreaths made from human hair, and other paraphernalia of grief in its inaugural exhibit: The Art of Mourning.

Entering Morbid Anatomy from an unremarkable, industrial street in Brooklyn, its ground-floor coffee shop/bookstore is buzzing. Families, hipster thirtysomethings, and laptop-toting student-types peruse books on taxidermy, histories of famous corpses, and Mexican death saints.

They’ve all come to this most unusual new museum for an education in archaic and folkloric rituals around death, taking form in exhibits of macabre subjects from grieving relics of the Victorian era to the art of taxidermy—and to mingle with the morbidly like-minded.

“It’s really a community clubhouse of people whose interests aren’t met by other organizations,” says Joanna Ebenstein, founder and director of the organization, of the eclectic group drawn to her new museum since it opened on the last weekend of June. “They feel like misfits but find each other here.”

In the midst of it all, Ebenstein is unassumingly eating lunch at a large communal table scattered with laptops and papers, plotting out the next few months of programing for her museum. Flanking her are two of her visiting scholars: Salvador Olguin, an expert on death culture and practices in Mexico, and Emily Evans, a British anatomist and artist, sketching on her computer drawing pad.

After a varied career of museum curating, photography, and book design, Ebenstein, 42, has merged all of these skills with her love of the dark and devilish, and turned this former nightclub space into an already-popular museum. She seems to juggle it all—writing, designing, sourcing, and hanging exhibits—employing what she calls “a very DIY process that I hope shows a lot of human heart.”

By shedding light on death, Ebenstein hopes to “get people to rethink what they think is creepy and dark and macabre and horrible,” and ponder how this prejudice reflects upon us and our modern society. Besides, what’s the big deal? “Death is a white elephant in the room,” she says. “We all know we’re going to die.”

The museum exhibit, housed in a single upstairs room, isn’t underwhelming or overwhelming, it’s just the right amount of whelming. The wall hangings, glass cases and descriptive histories can be taken in within a half-hour, leaving time to spare for the adjoining research library.

This Art of Mourning anchors in the 1860s, when Queen Victoria’s deep grief for her husband, Prince Albert, made mourning into a fashionable, and lucrative, business. But as the 20th century dawned, changing times, views on hygiene, and scientific advancements moved dead bodies from the parlor—now the “living” room—to the funeral home.

“You realize on a visceral level that this [having dead bodies in the parlor] is not a one-off thing, this is an activity people used to do all the time that now seems bizarre to us,” she says. “And it was only 100 years ago, so what has changed about us as a culture that this is unacceptable?”

It’s the type of exhibit that wouldn’t warrant a room in the marble-ceilinged, guidebook-listed museums of the world. But Ebenstein found that like-minded aficionados of such morbid relics as Victorian mourning hair art—worn or displayed to memorialize a loved one—are scattered throughout New York and thrilled to dust their treasures clean and show them off.

“Here’s their stuff finally being taken seriously, [because] where else would you show it?” she says. “These are things not traditionally of value: they’re not fine art, they’re not scientifically valuable. But they’re beautiful and they tell us stories about the past that we’re not seeing anywhere else.”

On the Morbid Anatomy museum’s opening weekend alone, which brought in 400 visitors, Ebenstein had three people approach her to offer up their personal morbid collections of such obscure interest as the human hair pieces currently on display.

Near one display of hair-constructed accessories—earrings, bracelets, rosaries—a placard reads: “Because human hair can last a century and is so intimately related to our individuality, it was seen as an ideal material from which to fashion sentimental keepsakes and memorials.”

An adjacent open door leads into the Morbid Anatomy research library, where books of all gruesome subjects merge with curio cabinets of tchotchkes, ephemera, and folkloric relics collected across the world—there are funeral home anti-fainting kits, plaster molds of limbs riddled with maladies, bottles of slimy who-knows-what, a mummified cat head. Ebenstein’s photography graces the walls: the taxidermied head of a bearded lady here, an Anatomical Venus—a deconstructed mold of a woman used as an 18th-century medical teaching device—there.

“This is our death-in-Mexico shelf,” Ebenstein says, pointing out a dark wooden case stocked with books. Filled with her own rare and out-of-print esoteric collection, the library offers a wooden desk under a dramatic chandelier for visiting researchers.

It’s this merging of serious academic study and bizarre folkloric subject matter that best represents what Ebenstein has set out to do. She’s built a “world in which I’m not a total geek,” she says, after years of feeling that the world looked down on her interests as trivial. “People feel so gratified there’s a place like this that takes what they like seriously.” She speaks with vigor about her projects, pointing out her favorite pieces in the museum and library.

Morbid Anatomy started in 2007 as photo project about medical museums, which turned into a popular blog, later blossomed into a 2,000-piece private library, then an events company, and now, a public museum. In December 2012, Ebenstein launched a Kickstarter for her anthology. An $8,000 request turned into $46,000 of donations. The first lecture she offered was standing room only. “It never occurred to me anyone else would be interested,” she says.

When she was approached in 2013 at a Brooklyn lecture (on Halloween eve by identical twin entrepreneurial sisters, no less) about turning the brand into a museum, there was little hesitation. A second Kickstarter campaign raked in $76,000, and in September, Ebenstein devoted herself to the museum full-time.

Morbid Anatomy, with Ebenstein at the helm, seems to do it all, from publishing books to leading international trips. Each month, a chosen theme colors the myriad events cramming the calendar. There are reading groups (next up: “Human sacrifice, eroticism and politics”), parties, film screenings, singles mixers, even a flea market with such macabre offerings as human ribs ($12 each). Totes, T-shirts, and an anthropomorphic stuffed rat are for sale at the gift shop.

The singles night began in March when a friend lamented that her date didn’t understand why she had to cancel in order to collect a dead kitten from a friend’s backyard and put it in her freezer. “I was like, ‘You can’t tell someone that—we live in a self-selecting world of weirdos,’” Ebenstein remembers. So, the pair set about tapping into that world to find partners who might appreciate the utility of a dead, frozen kitten.

With her permission, this friend launched the Morbid Anatomy singles mixer soon after, and met someone on the very first night who she’s been with since. In fact, Ebenstein says, waving over a slight, dark-haired man near the coffee counter, that’s him right there. “We had spoken in passing a sentence or two, but then we met-met,” he says, laughing.

The Art of Mourning will run until Dec. 4 and then be replaced by an exhibit on Dime museums, those P.T. Barnum-style displays that used to line seedy streets with offers of gawking at taxidermy, shrunken heads and exotic relics from faraway lands. Three years of Morbid Anatomy exhibits are already roughly plotted out, which, Ebenstein says with the tone of someone who basks in new discoveries, is “kind of depressing.”

But there’s plenty else to keep her preoccupied as these theme solidify. On the upcoming July calendar, highlights include such diverse topics as “Dissection and Drawing Workshop with Real Anatomical Specimens” and “From ‘Holy Gore’ to Santa Muerte: Death and Catholicism in Mexico.”

Below the main floor, a cellar seats 65 people for the museum’s multi-weekly lectures and events. Atop the building, an unfinished roof deck awaits the enticement of a soon-to-be liquor license.

“It’s a place that’s just as nice as a place for normal people—or more mass-market people,” Ebenstein says. “We should have something just as good. Just because what we like isn’t what everyone else likes doesn’t mean we shouldn’t have a really good time.”