When I think of writers and place, I first think of the great city writers, like James Ellroy, Paul Auster, Edith Wharton, and Judy Blume (not only did her books teach me about periods, sex, and religion, but they exposed me to the very idea of living in an apartment in New York City).

Then I think of the great writers of suburban misery (and drinking, and adultery), Updike and Cheever. Also central are writers who mine the social and cultural life of one very specific place throughout their careers, like Alice Munro’s obsessive return to Canadian small towns, Stephen King’s Maine, and Marilynne Robinson’s fictional Fingerbone, Idaho.

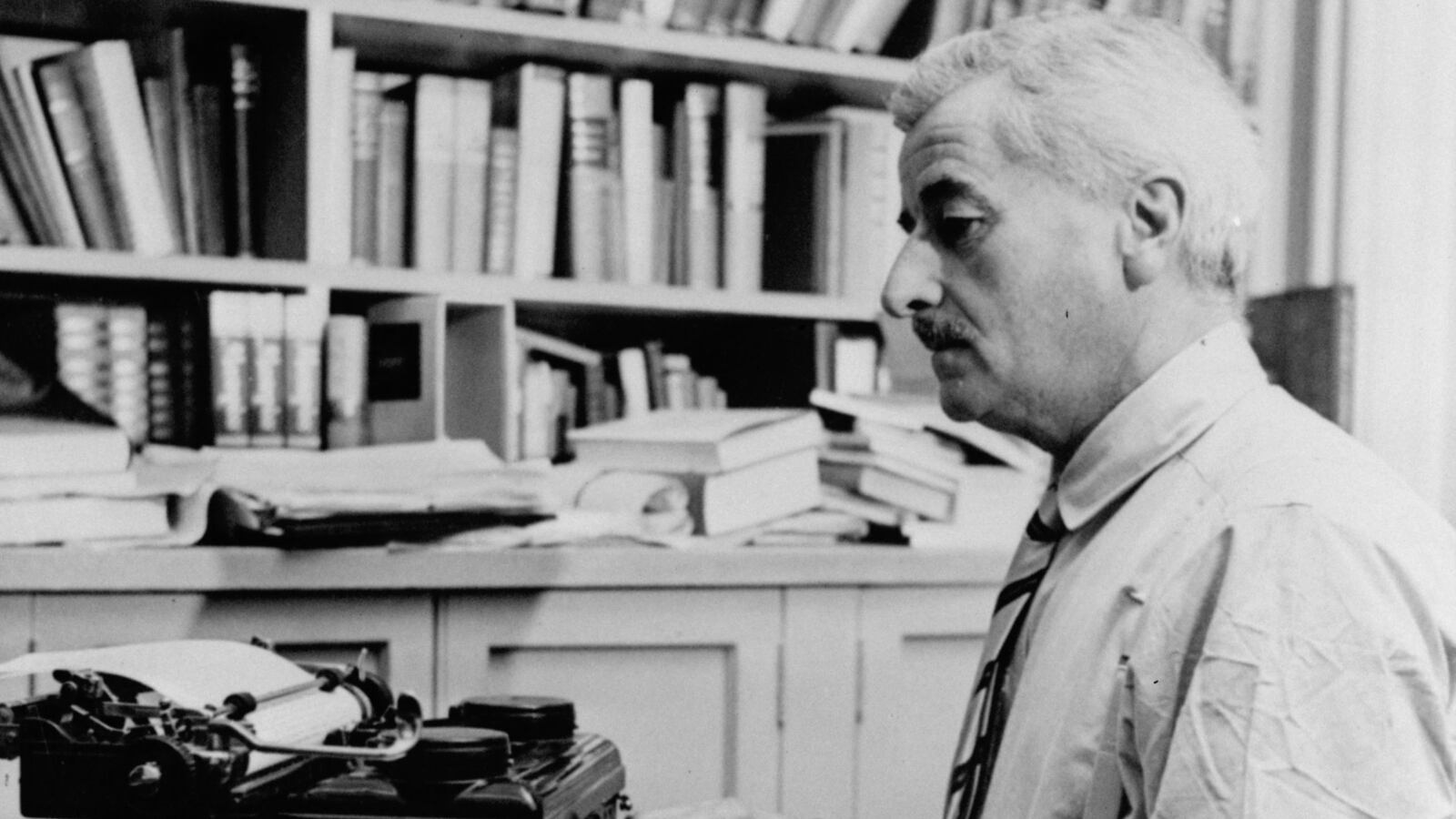

Then, of course, we have the Southern writers, such as William Faulkner, Flannery O’Connor, and Eudora Welty. I admire writers who can manage to conjure a physical place with all of its moving parts, with reference to real landmarks and particulars of dialect or lifestyle.

I delight in books that open with maps of towns or cities, that show me what it’s like to live in a particular social milieu during a particular time. I so prize this in other people’s writing because often, I struggle to fit my characters into a social world. My characters are often solitary, contemplating empty landscapes and their struggle to fit into them. I can get lost describing the way a forest sounds at dusk or that peculiar, cold stickiness of late summer nights, but ask me to describe a bustling subway or a general store and I have to draw on my powers of imagination. While my own writing isn’t tied to any particular region, it is thoroughly rural, full of isolated, lonely landscapes.

Until the age of 12, I lived primarily on 10 acres of woods on the outskirts of Bennington, Vermont, a small town surrounded by the Green Mountain National Forest. We lived in a tiny trailer that my mother had bought back in 1969, a trailer without running water or indoor plumbing. Our woods, though not as expansive as my mother would have liked (she longed to live in Alaska, in a place so remote nobody could reach it except by helicopter), were so isolated that in the summertime, I often went weeks without seeing anyone aside from my mother and later my stepfather and sister. In summer, when the trees were full, we could see no other houses. In the winter, through the clusters of bare birch trees, you could just barely spy the yellow trim of our closest neighbor’s house. My mother hated seeing their house: It reminded her how difficult it was to escape from the world completely.

My early years were a mix of acute loneliness and great freedom. Because I rarely had friends over to visit, rarely saw extended family, and had very little to do but wander around the woods or lay out on the lawn and read, I turned to books and my imagination. I imagined that the forest around me was animated. I didn’t really believe in God, I wasn’t raised with much religion but an incoherent mish-mash of Catholicism and New Age philosophy, but I believed in the possibility of magic, that the world was bigger than me and that if I listened carefully, I might understand the ways that it all fit together. I wasn’t always happy, though. Our land often seemed like a prison, with the mailbox at the end of our steep, gravel driveway the farthest point I was allowed to venture out alone. The paved road was close enough to give me fantasies of walking down toward that distant roaring to stick out my thumb to hitch a ride to someplace new. I never did it, though—I was a kid, and my fear of consequences was greater than my bravery.

Despite the confinement, those early years were often idyllic. I spent entire days in the woods, sprawled out in the pine needles and clover patches, spinning stories of myself as a detective, a princess trapped in a forest by a wicked witch, or a supernatural creature who did not quite belong to this world.

My mother spent her days reading books about herbal medicine, taking care of our many dogs and cats, identifying plants from our Reader’s Digest Guide to North American Wildlife book, and sweeping obsessively. Sometimes she’d receive letters from people she corresponded with, like psychics, who were constantly warning her of ominous interference from people who were “working against her,” influences they could eliminate for a price. She accepted their predictions as true, but couldn’t afford their help, or perhaps did not want it. The world working against her was yet another reason to remain isolated.

While my mother wished for ultimate isolation, I felt torn between the desire to connect and the pleasures of being alone in nature. This tension shows up in everything I write: The characters in my fiction are often trying to figure out how to find a home when being with other people feels both confining and comforting.

When I was 12, we moved away from my childhood home in Vermont. My mother, tired of such close proximity to her family and the encroaching development near our property, sold the land for cheap, bought a travel trailer, and set us all out west. She imagined the West as a place full of potential and wide, open spaces. She wanted it to be the West of Louis L'Amour novels and John Wayne movies. She wanted to live in a place where people would be friendly and where she could have her fantasy of acres and acres of land and endless skies.

We set off for Wyoming, where she quickly discovered that land was too expensive. My mother, as always, had very little sense of how much money could buy. We went south after that, ending up in Oklahoma, almost penniless. While driving along an isolated stretch of highway in the Oklahoma Ozarks, we saw a hand-painted sign stuck to the side of a wooded mountain: Land for Sale. It was a mere 400 dollars an acre. We bought 10 acres on the spot.

I think the writer is often this figure, at least in their own consciousness, of somebody standing slightly outside the flow of everyday events. That is the kind of person I truly became while living in Oklahoma. There, we lived on a mountainside, by a rural highway 15 miles from the closest small town and more than an hour from a “large” town (McAlester, with a population of less than 20,000 people).

The woods around our trailer seemed dangerous and foreign. My mother killed a copperhead under our porch the first week we lived there and showed me the severed head, which was enormous, the cheeks puffy with poison. There were spiders, scorpions, and tiny cactuses, which stabbed my feet when I tried to walk barefoot outdoors, as I always had in Vermont. It was easy to imagine that the landscape was actively trying to repel us.

The highway, too, provided a sense of danger: The T intersection near our house was plastered with reflective markers along the guardrail, signs warning cars of the sharp drop beyond it. The warnings didn’t seem to matter. Frequently, we’d drive past on the way home from McAlester to find the guardrail broken, detritus of a car accident strewn all over the highway. The winding, narrow highway near our house was dotted with makeshift memorials, crosses and ribbons printed with the names of the dead growing pale in the sun year after year, sometimes multiple crosses and ribbons at particularly dangerous intersections. I got a sense that people died out on this empty stretch of road all of the time.

Now, when I visit rural Oklahoma, I can see the beauty. My in-laws live deep in the woods, and I always take a moment to step outside at night when we visit. Out there, we are so far from artificial lights that the sky is almost alarmingly filled with stars after dark. The bugs are so loud that stepping into the darkness feels like being surrounded by an enormous, pulsing heart. Still yet, that danger I felt when we first arrived is what draws me to writing about Oklahoma. Vermont provided me with a fairy-tale childhood. In Oklahoma, the landscape could leave you broken. You were surrounded by things that had lived long without you and would continue to live long after you were gone, like the scorpions and snakes and armored armadillos that lay bloated on the side of the highway.

Since I left Oklahoma, I’ve largely lived in cities or suburbs, but those spaces rarely ever make it into my writing and I find it difficult to remember the physical details of Columbus, Ohio, or Tel Aviv, Israel, or any place I’ve lived that isn’t Vermont or Oklahoma. Rural places are the only places I’ve ever really known, and when I am writing about them, I feel confident that I know the terrain.

I imagine myself, someday, living in the woods again, in a place where I don’t have to see cars, where I am not constantly confronted with the greetings of well-meaning neighbors, where I can smell the dirt thawing in spring and feel the air change at night in early September. I want to know, as I often did in Vermont and Oklahoma, that I am a part of nature, that like the dead animals I’d find on a hike, I was mortal, and that no house or neighborhood or city would keep me from that eventuality, as much as gated communities and landscaped lawns try to mask the everyday presence of death. Forests, lakes, and dark, starry skies are a permanent part of my creative life and draw me back, over and over, to the strange and liminal territory of rural America.

Letitia Trent’s first novel, Echo Lake, will be published this month by Dark House Press/Curbside Splendor. Her work has also appeared in the Denver Quarterly, The Black Warrior Review, Fence, Folio, The Journal, Mipoesias, Ootoliths, Blazevox, and many others. Her first full-length poetry collection, One Perfect Bird, is available from Sundress Publications. Her chapbooks include You aren’t in this movie (dancing girl press), Splice (Blue Hour Press) and The Medical Diaries (Scantily Clad Press).