They were sitting in the Crossroads of the World, lounging in the dark in stadium-style seating in the heart of one of the world’s capitals. Outside, the neon marquees lit up the night.

But for two hours, they were a punch line.

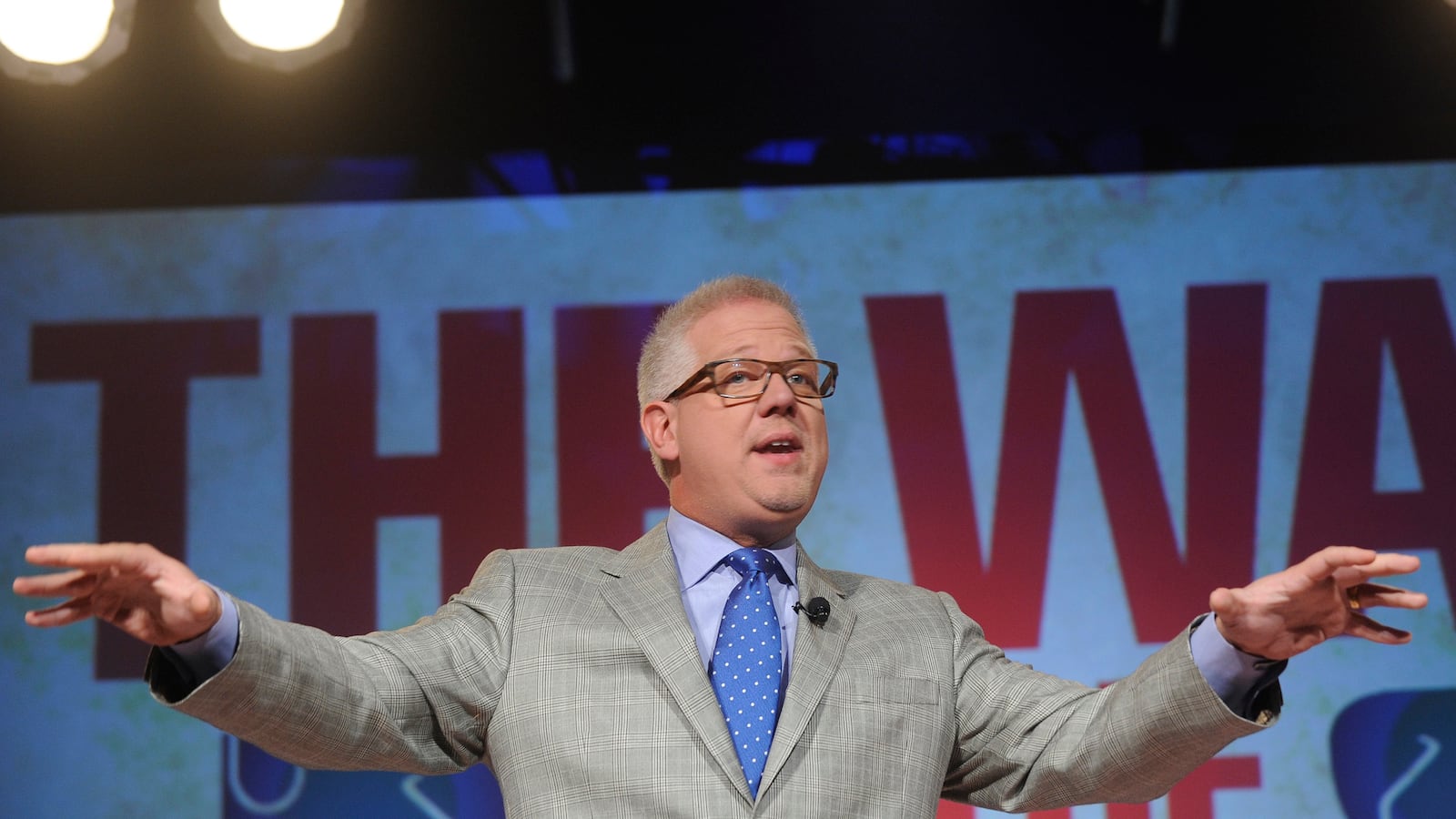

Early on in the live simulcast of “We Will Not Conform”—a rally against the Common Core educational standards hosted by the conservative media star Glenn Beck, which was broadcast to thousands of theaters around the country—Beck joked that some of the members of the nationwide audience were likely jostling over scant space on the elbow rest in crowded theaters in the nation’s heartland, while others were probably sitting alone in the vast darkness, a movie screen all to themselves.

This last group, Beck speculated, was surely in New York City.

And so the 20 or so people, sitting alone at the Empire 25 in Times Square, chuckled quietly.

Common Core is a set of standards pushed by the Obama administration and adopted originally by 45 states as part of the 2009 stimulus bill. Although the Obama administration insists that Common Core increases college readiness and prepares students for a 21st-century economy, it has been fiercely resisted by the mostly liberal teachers unions, who say that it already adds to the large burden of high-stakes tests and makes teachers follow a rote set of curriculum instructions, and by conservatives, who say that the standards are a federal infringement on what has traditionally been a local concern.

These dual complaints have made for some strange bedfellows. On Tuesday night, Beck sought to bridge the divide, telling the audience that what really mattered were not political differences, but “the children,” a word combo that Beck can scarcely cite without his eyes welling.

And he sought to demonstrate the kind of collaboration he was encouraging by decking out the home studios of his network The Blaze—the same soundstage, he was careful to note, that saw the production of JFK, Prison Break and Barney—with teams of working groups who sat at round tables amidst the studio audience, beneath a large chalkboard, which went unreferenced by the host, but which featured his trademark swirl of connecting lines and arrows, and with the phrases “SECOND AMENDMENT” and “DISTRIBUTE THE WEALTH” writ large and central.

There was one table devoted to “research,” which, put in practice here, seemed to mean assembling talking points to win an argument. There was another devoted to politics, which featured David Barton, a conservative activist and historian whose book The Jefferson Lies (which argues, among other things, that the third president’s commitment to the separation of church and state is overstated) was voted by the History News Network as the least credible book in print. One table focused on grassroots organizing, another, led by a crisis communications expert, on “Messaging,” where the audience was warned not to call Common Core “Obamacore” or speak about how it was a sure sign of a coming Communist takeover—“even though it may be”—for fear of alienating moderates.

But despite Beck’s insistence on collaboration, on putting aside name-calling and political differences, and working together in a cloud of love, faith and collaboration, he couldn’t help but fall on the Beckian habits of old, the ones that helped spark the Tea Party uprising from his old perch at Fox News.

Among those on the outs in Beck’s lovecloud: “Edu-crats,” PhD’s in early-childhood education, progressives, the State of California, Bill Gates, teachers who want lessons grounded in facts rather than stories, the IRS, the NSA, the U.S. Chamber of Commerce, elite opinion, people who think they know how to educate your children better than you, and corporations, which Beck—despite admitting that he would have been appalled to find himself saying as much only a few weeks ago—accused of using the new standards to fatten their own wallets.

There were no teachers present at any of the workshop tables, a glaring oversight considering how much they could have found common cause with much of the message, and one that would have reinforced the central theme of coming together around differences.

There were educators, to be sure, but they were not the type who could be much help to desperate school parents. One operated a charter school, and whenever Beck turned to him, he advocated for a return to the kind of classical education that America’s founders would have received in the 18th century, and accused Common Core of trying to brainwash children with “progressivism.” The other was a dean for the online curriculum at Liberty University online, the home-schooling K-12 outfit associated with the institution of higher learning founded by Jerry Falwell. He spoke of the virtues of home-schooling, and indeed, one of the roundtables in the studio was devoted to “alternatives” and was mostly convincing the audience to scrap the public school system entirely and teach the kids around the kitchen table.

There was one person affiliated with the public school present, a former assistant principal from Florida who quit in protest of the encroaching Common Core standards. Beck lavished attention upon her—mostly, it seemed, because she had been seduced by his charms. “She hated me,” he said, while asking her to describe for the audience exactly how she used to throw things at the TV when he was on.

Beck brought her up from the table and onto his couch, their conversation a living example of the kind of differences that could be overcome. He said they put aside their political differences, their differences over issues like gun control, and would leave them for another day.

“We can arm wrestle over that,” he said, “Of course, I am going to win. Because I got a gun.”

Towards the end of the performance, Beck asked for someone in the audience in all the theaters across the land to stand up and serve as a local leader, whom others in the audience could come to and who could organize participants into some sort of coherent movement.

In Times Square, at least, no one stood. Rather, at the end, the audience—which, it turned out, consisted mostly of teachers, headed toward the exits.

“I liked it,” said one to her colleagues, “But I just wished he was a bit cooler.”

Another, trying a bit of the humor that teachers are known for, told his colleagues, “I liked it, too. But why was it called Godzilla? Oh, wait, was I in the wrong place or something?”