The end is here, but for cub detective Henry Palace, there is still one more case to solve—that of his missing sister.

Ben H. Winters is out this July with the eagerly anticipated finale to his critically acclaimed The Last Policeman trilogy.

World of Trouble deposits the reader a few months later from the last time we saw the detective. Palace, for those unfamiliar with the series, is a still wet-behind-the-ears detective in Concord, New Hampshire. The books follow him as he tries to crack open pretty standard crime novel fare—a suicide that may be a murder in the first book and a missing person in the second.

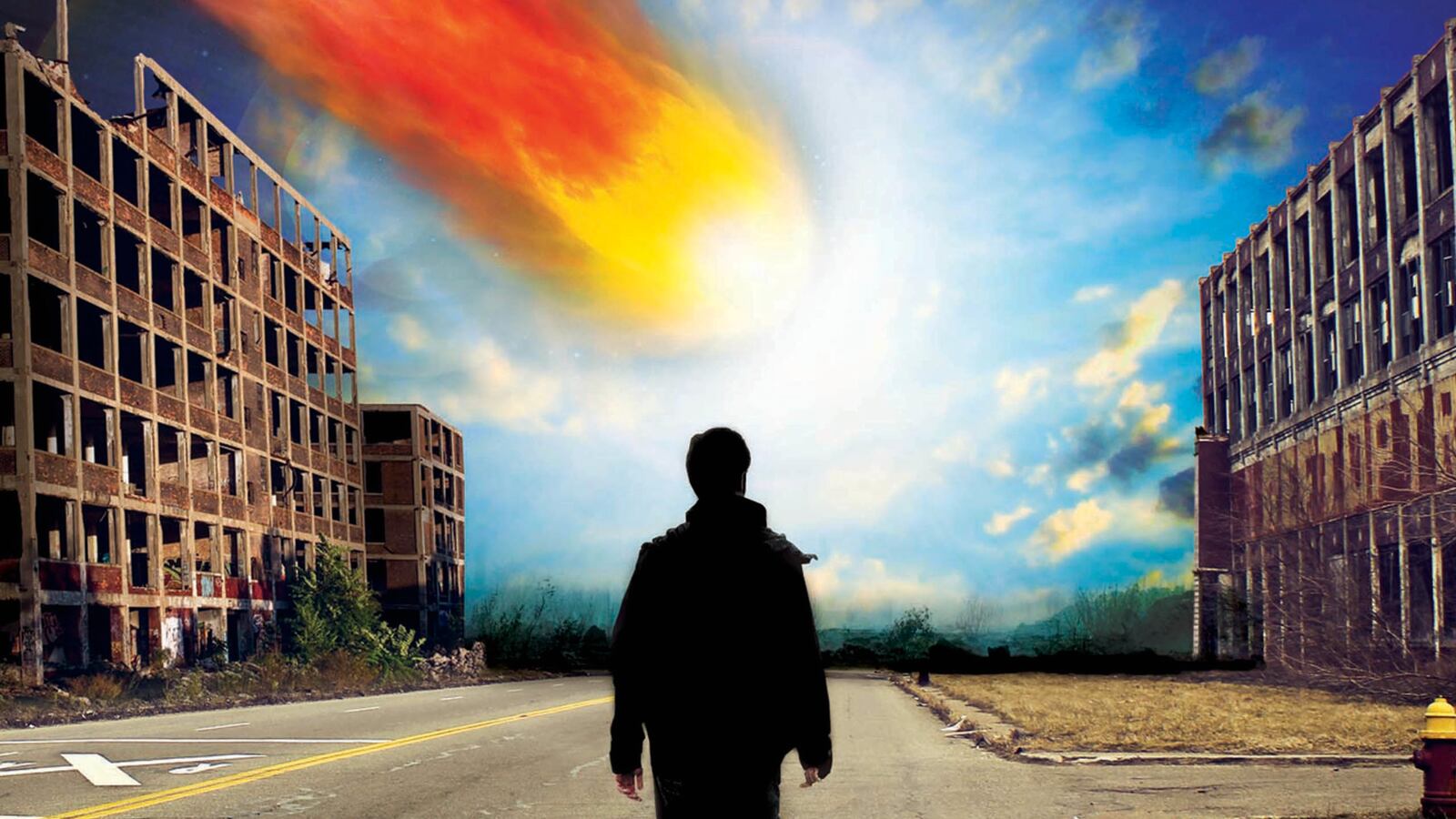

What makes the books atypical fare is that they are set against the backdrop of a world about to be destroyed by an asteroid named Maia, or 2011GV1. Winters uses that cataclysmic event to examine the slow deterioration of communal life in the face of annihilation. What is ironic, and what causes so much trouble in the world he builds, is that scientists know over a year in advance that an asteroid is going to hit—and just months before, the exact date.

This provides just enough time for the world as we know it to cease to function—the markets, transportation, hospitals, and so on, all crumble. The great danger to the economy is no longer uncertainty, but certainty. Men and women “go on bucket list,” some commit suicide, and others go full on doomsday hoarder.

Palace, just a patrol officer, is called up to detective when officers disappear. After solving two seemingly impossible cases in the first and second book, he is now on the most important one of all—finding Nico, his wayward sister.

Just as the end of the world gives rise to hedonist parties in New Orleans and neighbor-on-neighbor violence, it also gives rise to that other great American tradition—government conspiracy theories.

Nico is part of a group of young hardcore activists who believe the U.S. government has covered up a way to defuse the asteroid because the government thinks it can rule in the chaos afterward.

To find his sister, Palace must not only contend with the Hieronymus Bosch-like world exploding all around him, but also that all he has at his disposal are a notepad with a dwindling number of pages, a bicycle, a trusty dog, rote memorization of a training manual, and a determination to do right that makes one’s heart ache.

Winters’ clear prose delivers a work that combines a pleasurable read with deep insights into fault lines in our society—a rare feat these days. Those who read it might find themselves haunted by a simple question—what would you do if you knew the world was going to end?

Surrounded on all sides by people stripped down to naked self-survival, Palace is driven and haunted by memories for the past. His insatiable need to know why something happened, which is what makes him a great detective, can be traced to the inexplicable murder of his mother, who was randomly gunned down in a parking lot. His quest to provide order in a Lord of the Flies world with guns entertains and saddens.

For most of us, whether or not Nico is missing or dead would seem irrelevant as the days left dwindle. Knowing the bigger ending—that the world is going to end at the end no matter what—might ruin the tension for the reader. And yet the book drips with suspense. Whereas before, his books were mostly linear in layout, Winters utilizes a series of flashbacks to cover the time passed since book two and to catalogue the ways in which an already shattered world has gotten worse.

Winters’ style is a slow burn. His detective novels contain none of the twists that strain credulity so often relied upon by thriller novelists. His story is largely devoid of wanton violence and gratuitous sex. His cadence is a steady beat rather than a roller coaster, and his words sparing and simple. They will stay with you.