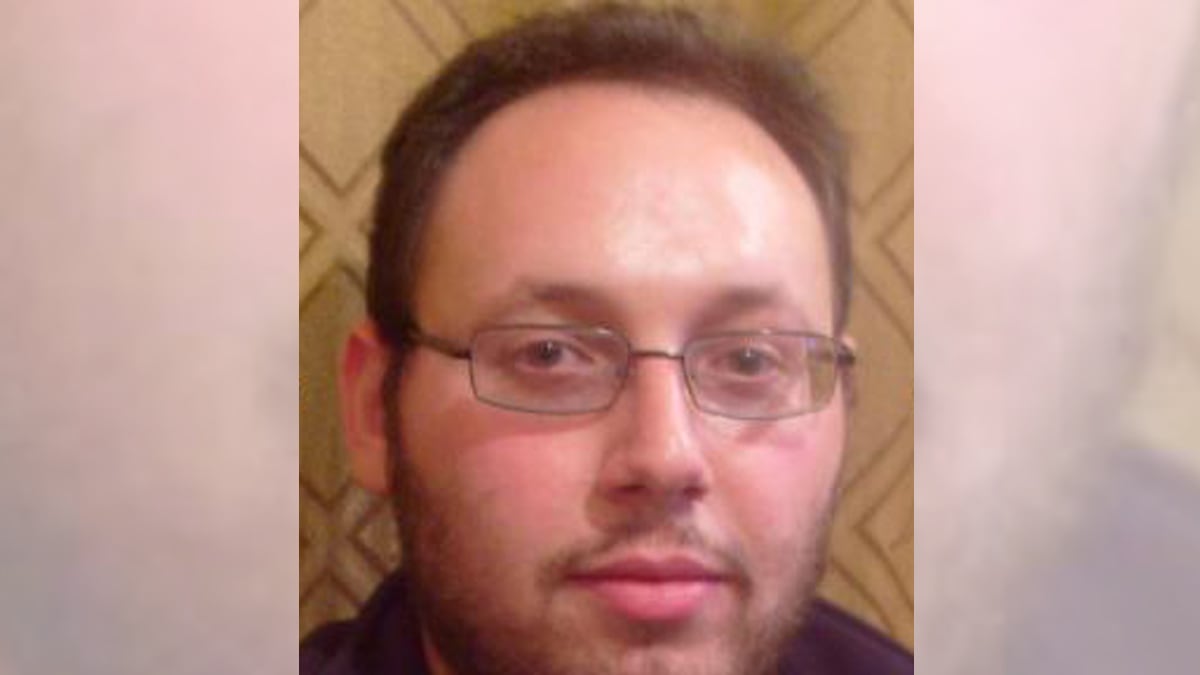

Editor's Note: ISIS claims to have executed Steven Sotloff on September 2, in a videotaped beheading.

When pro-regime and anti-government factions started killing each other in the 8,000-year-old Syrian city of Aleppo, a little town in Turkey called Kilis blossomed into relevance at their expense. Located just four miles north of the Syrian border, Kilis became a vital crossing point in and out of a rapidly devolving war.

If you were to wander into the decrepit Hotel Istanbul in the center of Kilis last summer and sit in the lobby for a few hours, you’d trade wary glances with bomb-chasing photographers, ragged aid workers, desperate Syrian refugees, war tourists, and a couple of European Muslims looking to join what was then known as the Islamic State of Iraq and al-Sham. From the hotel’s upper floors, you could see smoke billow on the horizon from airstrikes and shelling light up the sky at night. If you entered a guest room, the pungent odor of the air freshener dangling from the grimy mirror might lead you to discover that it was, in fact, a urinal cake. A German magazine called it the “Hotel of Madness,” and at times, the place really did better resemble an asylum than professional lodging.

Steven Sotloff checked into Room 303 at the Hotel Istanbul on August 1, 2013. It was a dodgy time to be at the Turkish-Syrian border. Jihadist fighters had recently snatched several Western journalists and aid workers on the road connecting Kilis to Aleppo, and rumors were flying that Westerners might even be under surveillance in Kilis. It was said that spies on the Turkish side could be tipping off jihadis and criminal gangs on the Syrian side. Those groups were eager to get their hands on anyone who could be used for ransom or political sway.

By the time Sotloff arrived in town, the flow of journalists in and out of Aleppo had diminished to less than a trickle. Local fixers were hurting for business, especially those whose clients had been previously targeted for kidnapping attempts. Many of them started taking some of the odd jobs in town just to stay afloat.

One fixer, whom I’ll call Mahmoud (not his real name), even took the mother of a dead Italian jihadist to Aleppo’s front lines so that she could see her son’s corpse decaying in the street, irretrievable and surrounded by government snipers. Other fixers had taken in various war tourists and crazies, but were growing increasingly nervous that a fool might take out a camera at the wrong checkpoint and get them both in trouble with the Islamic State.

Sotloff had been to Kilis before. He’d been to Syria in wartime, too. And in the recent years leading up to the date of his abduction, he’d also reported courageously in Libya, Egypt, and Yemen. He was experienced. He could speak Arabic. He was careful. And he told me he had had enough.

Over beers at Kilis’ only bar, Sotloff told me he was sick of being beaten up, and shot at, and accused of being a spy. Just the day before, Turkish police had hit and pepper-sprayed him for taking pictures at a protest in a nearby city. He told me he wanted to quit reporting for a little while, at least on conflict in the Middle East, and maybe apply to graduate school back home in Florida. But first he wanted one last Syria run. He said he was chasing a good story, but kept the specifics close to his chest.

Last time he’d been in Syria, a government sniper nearly killed him after spotting the tiny glow of his cigarette through a bathroom window while he sat on a toilet with indigestion. The sniper barely missed, and Steven relayed the story as equal parts humorous and traumatic.

This time, Steven had arrived in Kilis after dark, and planned to be in Syria the next morning. He’d only stopped in town to pick up a borrowed flak jacket, he said. His timing was cautious, and the bar was a discreet 50-foot walk from the hotel.

Security and logistics were more critical than ever, and we soon drifted onto the topic of reliable fixers. He asked about a Syrian man he planned to meet the next day, a fixer whom I’ll call X (not his real name). A fine fixer, I had heard from correspondents who knew him, but there had been a problem recently. A relevant problem.

***

A Canadian man I’ll call “Alex” (also not his real name) wanted to photograph in Syria, and joked that he was tired of shooting pictures of dogs and flowers back home. Though he admitted to me that he had never worked in conflict, Alex was quick to add that he had photographed student protests in Montreal. Now he had come to Kilis intending to enter the world’s deadliest war zone, but seemed to have difficulty grasping some of the logistics involved in minimizing risk.

It was the very end of July, and the Islamic State of Iraq and al-Sham had proven its effectiveness in infiltrating once-moderate areas and implementing a brutal interpretation of Sharia law. Many of the European fighters in the Islamic State kept social media accounts to document their trips, and used them to encourage other young extremists to join them in Syria.

Sometimes they’d post pictures of themselves in swimming pools, fancy cars, and looted villas, advertising Syria as a “Five-Star Jihad.” Other times they’d share photographs of themselves holding—even kicking around—the decapitated heads of Shia Muslims, posting with hashtags like #mujahideen #kafir (infidel) #jihad and #ISIS. And when Alex came to town, the Islamic State had an established presence in A’zaz, Syria, within sight of the border.

Alex told me he had asked journalists with Syria experience to connect him to their fixers, but none had delivered. They told him not to go to Syria, he said. Syria was never really a war for first-timers, and least of all by mid-2013.

He then asked if I knew any fixers. There was one I trusted immensely, Mahmoud, the fixer who had taken the Italian jihadist’s mother to the front lines. And since Alex intended to go into Syria despite the warnings, better that it be with someone trustworthy.

But Mahmoud declined because of Alex’s lack of experience. “Three months ago, fine,” Mahmoud said. “But now we’ve got the Islamic State at every checkpoint between here and Aleppo, and I’d be risking my life if he does something stupid.”

It didn’t really matter, though, because Alex told me he had already turned to Facebook and made arrangements to go into Syria with someone he’d never met. Alex and I decided to meet up for a final cup of tea the night before his expected crossing.

At the café, Alex detailed his method for finding this new fixer. He said he had written to approximately 30 Syrians he found through Facebook, selecting those who displayed guns or opposition flags in their profile pictures. He told them he was a photographer and wanted to go to Aleppo, and asked if they could help. A dozen or so wrote back.

Fortunately, Alex decided to work with X, who was an established fixer with a clean safety record, and who worked at the rebel-aligned Aleppo Media Center. But Alex also told me that he’d subsequently written to all the other men to inform them that he no longer needed their services because he had already made arrangements to cross with X the next day at 10 a.m.

Up to that point, I had been patient with Alex. But now X’s life was also on the line, and he didn’t even know it. Aggressive berating fell on deaf ears.

“I already spent $1,500 to fly here,” he said decisively. “I’m going in.”

I went back to the Hotel Istanbul and wrote to a journalist in London who had far better Aleppo connections than I. Early the next morning, she forwarded me a response from an Aleppo source with whom she had been in touch about Alex’s situation:

“He’s under a [sic] big danger if he enters Syria, some of my contacts told me that some people are getting some informations [sic] about him, about his nationality, they know where he’s staying in Kilis, and they know that he’s supposed to come with X as a fixer tomorrow in Aleppo… tell him to be careful and that he’s under danger and people are monitoring him.”

The journalist in London forwarded the warning to Alex, too, and he finally decided to go home. I breathed an enormous sigh of relief when Alex left Kilis that morning, just two hours before his 10 a.m. appointment with modern terrorism.

X was then warned of the near miss via a correspondent who had worked with him in the past.

UPDATE: After this article was published, a conflict photographer who identified himself as 'Alex' wrote to The Daily Beast and disputed certain points in the story. He said that he had secured the fixer, ‘X,’ through a fellow Western journalist, and not by writing to 30 Syrians via Facebook. The photographer says that after he talked with Taub about the fixer, a Syrian visited his hotel room at 2 am on the morning that he was supposed to enter Syria. He says that this man told him that he was a good friend of Taub's, that he was aligned with the Free Syrian Army, and that the man warned him not to enter Syria. At this point, the photographer says, he decided that too many people knew about his trip and so he decided to postpone it. He also pointed out that a representative for Sotloff's family has said that Sotloff was sold to ISIS by moderate rebels—in contrast to what the White House has claimed.

***

Two days after Alex left town, Steven Sotloff asked what I knew about X. Was he a good fixer? So I’d been told. Trustworthy? Apparently, yes. Safe? Unlikely, given the preceding days. I told him about what had happened with Alex. Mahmoud, the other fixer I trusted, hadn’t been compromised, and his record remained unblemished. So I passed Sotloff his contact information. We drained our glasses and called it a night.

On August 5, I had dinner with an Italian journalist fresh out of Aleppo. The Islamic State was closing in on the media center, she said, still trembling from a mix of adrenaline and fear. They had to leave two days early. And now the jihadis had a checkpoint within sight of the border. That wasn’t there when the journalists crossed into Syria a week ago.

She asked if I had heard anything about the fixer, X. I had not. She was concerned because his wife had come looking for him at the Aleppo Media Center. X’s wife told the Italian that he had gone to meet an American journalist.

By the following afternoon, confirmation trickled in that Sotloff and X had been kidnapped together within minutes of crossing the border on August 4. Nobody knew exactly who had them, but the recent alerts of spontaneous Islamic State checkpoints and increasingly frequent abductions made that group a likely suspect.

I don’t know what happened between our meeting in the late hours of August 1 and Steven’s ultimate decision to go into Syria with X two days later than originally planned.

***

The relevant people informed Steven’s family of his disappearance, and his family ultimately decided to keep a media blackout on the case for a multitude of reasons related to strategies for negotiating his release. A few Syrian activists tweeted about his abduction last August, but online nudges got most of those early tweets taken down. Meanwhile, the international press stayed diligently silent.

That is, until Tuesday, when the Islamic State released a gruesome video that apparently showed a fighter with a British accent murdering James Foley, a well-known freelancer whose disappearance in 2012 was widely publicized. According to those who have seen the video, the Islamic State subsequently displays a man who they claim is Sotloff, threatening that he will be next if the United States continues its military operations in Iraq.

Today the Islamic State has not just Sotloff, but the entire global media in its clutches. They kidnap, ransom, and kill journalists, and therefore have a near-complete monopoly on information from within their boundaries. They decide which pictures get released, and even threaten local photographers with death if they do “anything that damage[s] IS’s reputation.” Last month, Vice News aired an extraordinary five-part documentary with unprecedented access within the “Caliphate,” but remains silent on what degree of editorial control the Islamic State may have had over the raw footage.

And now—after a year of measured silence within the international media, a year during which not one major news outlet announced “American journalist Steven Sotloff was kidnapped in Syria”—the Islamic State superseded his family’s wishes and ended the media blackout on its own terms.

The release of Foley’s murder tape, and the subsequent threat that Sotloff could be next, is not directed at the American government. The State Department has known about Sotloff’s disappearance for over a year. It is an attack on the American public, to whom the now-viral revelation of his abduction is brand new and utterly shocking, especially following Foley’s gruesome murder.

Twelve days after their initial disappearance, X, the fixer, was released by his captors, and allowed to return to his wife in Aleppo. By that point, I had left Kilis and was pleading with the Canadian photographer to share the list of Syrian strangers he allegedly contacted while trying to make his own arrangements to visit Aleppo, as well as his communications with them. Perhaps X and the people working on Sotloff’s abduction case could identify the ISIS informant from those conversations.

But suddenly Alex grew reluctant to talk. His final message before blocking me on Facebook in late August last year read: “I don’t have time for that, stop bothering me, I have nothing interesting for you anyway."

Ben Taub is a 2014 graduate of Princeton University, a member of the Frontline Freelance Register, and will begin an MA at Columbia Journalism School at the end of the month. He spent 10 weeks in Kilis over the last two summers while documenting unusual people and happenings on the fringe of Syria’s war.