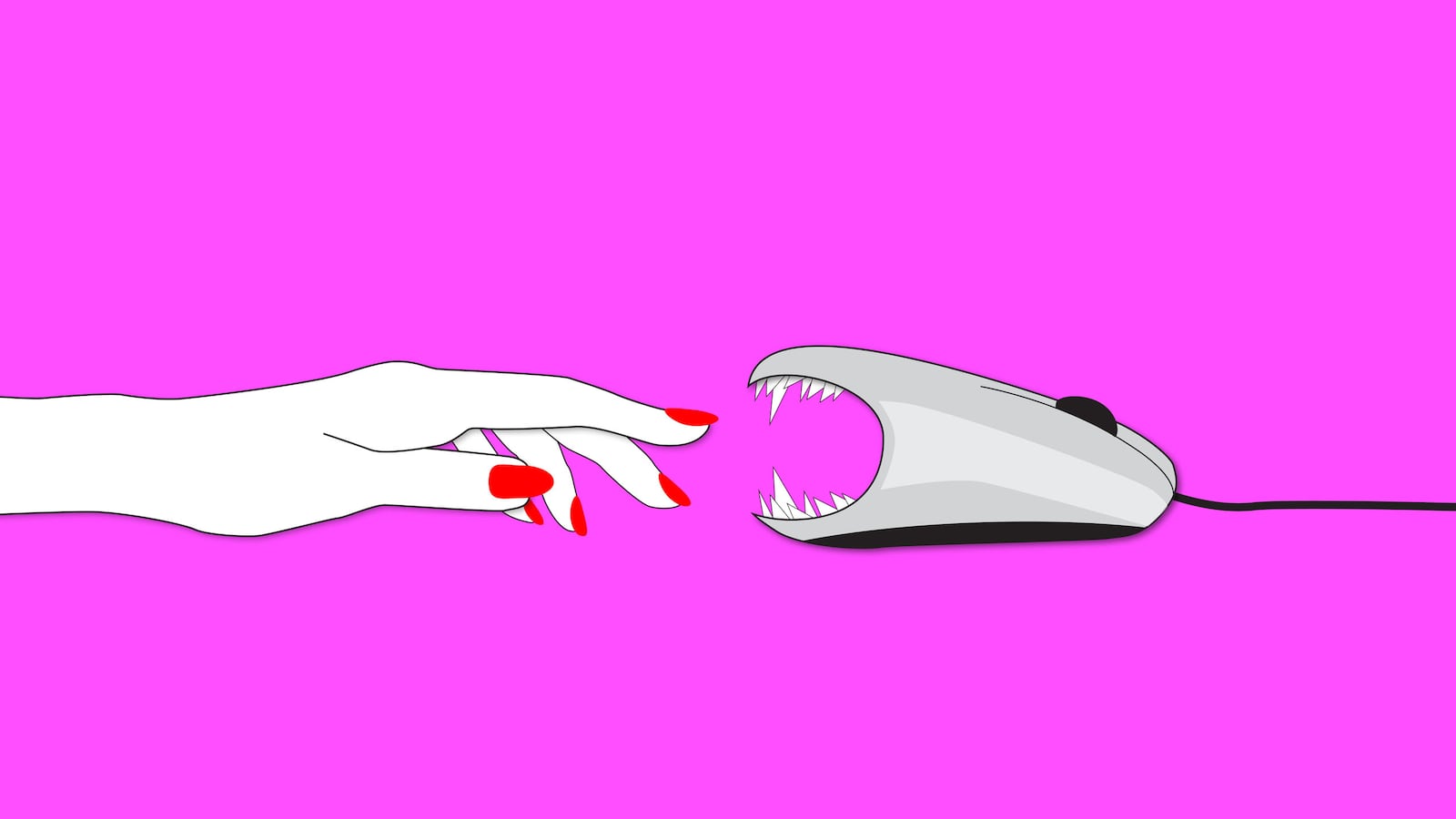

August has been a nightmare for women on the Internet.

The editors of the feminist blog Jezebel had to publicly call out their employers at Gawker Media for refusing to permanently ban commenters who spammed the site with animated images of rape and sexual assault. The popular web forum Fark.com felt it necessary to add “misogyny” to the moderator guidelines in order to combat the presence of rape jokes, as well as slut-shaming and victim-blaming language. Robin Williams’ daughter Zelda was forced to leave Twitter after receiving waves of harassment following the death of her father. And while Twitter has promised to reevaluate its policies in the aftermath of Zelda Williams’ departure, many female Twitter users, as Slate reports, still have to rely on third-party blocking tools like the Block Bot, Block Together, or Flaminga, in order to clear their Twitter feeds of harassment and abuse.

After a month like this one, it’s worth asking: Will the Internet ever be a safe place for women? This question might seem naïve. If you are a woman with an online presence, after all, you may have grown so accustomed to Internet harassment that you cannot even imagine an alternate future. A recent poll from the Rad Campaign, Lincoln Park Strategies, and Craiglist founder Craig Newmark found that 57 percent of people who experience abuse online are women.

While this data might lead one to believe that women are only marginally more affected by Internet harassment than men, Amanda Hess at Pacific Standard puts a more qualitative face on this quantitative data. Nearly three-quarters of people who report harassment to the organization Working to Halt Online Abuse, she notes, are women. Internet “accounts with feminine usernames” also receive “100 sexually explicit or threatening messages a day” compared to less than four per day for accounts with masculine usernames. Hess concludes, “the vilest [online] communications are still disproportionately lobbed at women.” For women on the Internet, vitriolic abuse is simply a fact of life.

We are accustomed to thinking that the prevalence of sexist Internet harassment is a problem with people rather than a problem with technology. Accordingly, most efforts to make the Internet a more hospitable place for women are reactive approaches that seek to address problems after they take place, rather than proactive approaches that seek to prevent harassment at its technological roots. The only way the editors of Jezebel could try to stop their “rape gif problem,” for example, was to “individually” and “manually” delete comments and ban commenters. Even then, commenters could continue making new accounts and posting more explicit images. Gawker Media has since stepped in with a back-end fix that hides comments from new users until Jezebel or another approved commenter has approved them.

Twitter, on the other hand, still places no restrictions on users who create multiple accounts, while also requiring users who are being harassed to fill out a needlessly lengthy report if they want the problem to be properly addressed. For women who receive large volumes of harassment from multiple accounts at once, Twitter’s reporting requirement is akin to asking someone whose house is on fire to provide an inventory of all her possessions before sending firefighters to the scene.

If it seems like all we can do is hack at the branches of this problem rather than its roots, maybe it’s because we’re too focused on the people who use technologies rather than the technologies themselves. In other words, if we accept sexism as the more or less inevitable feature of our social world that it seems to be, efforts to combat Internet harassment would more properly be aimed at publishing platforms and social media services themselves rather than their users. Jezebel’s particular problems, for example, stem from the fact that “IP addresses aren’t recorded on burner accounts” on its publishing platform, Kinja, leaving staff with no way to permanently ban repeat offenders. Twitter, too, could likely place restrictions on the creation of multiple accounts within a certain time frame, but has opted to address harassment through block functionality instead. Kinja and Twitter are perfect examples of platforms and technologies that could have been built differently.

So why weren’t they? Danilo Campos, a mobile developer who recently offered Twitter a list of suggestions to “protect its users,” speculates that “it’s because their team is so overwhelmingly not comprised of the marginalized groups” who are most affected by Twitter abuse. Indeed, Twitter’s total employee base is 70 percent male and its tech employees are 90 percent male. Facebook—which houses 62 percent of online abuse—is nearly 70 percent male as well.

And given that sexist Internet harassment and racist Internet harassment also compound each other’s effects, it’s also worth noting that both Twitter and Facebook are overwhelmingly white. When Gawker’s Valleywag shamed Twitter and Facebook for their diversity numbers, Gawker editor-in-chief Max Read was forced to admit that he doesn’t even know their own figures but believes they are “bad.” The technologies that we use to communicate with each other online, it seems, were built and continue to be operated by the people who can feel safest on those technologies. These platforms are like 4-foot-wide roads built by motorcycle riders: Those of us stuck in cars are left wondering how we fit in while motorcyclists zip past us.

Recent data, too, suggests that the gap between the people who run the web and the people who use it is widening along gender lines. Marketing firm Digital Flash discovered in 2012 that Facebook and Twitter are dominated by women, with a 58 and 64 percent female user base respectively. Women, they found, are also more likely to update their statuses daily and comment on others’ photos and statuses daily. But Digital Flash’s data also reveals that women, understandably, rely on social networking privacy controls more so than men, with nearly 70 percent of women setting their profiles to private. Despite being the most avid Internet users, then, women are expected to do extra work in order to make their online experience safer and more pleasant. One might think that sites like Twitter and Facebook would have a vested interest in adapting their technology to better accommodate their powerhouse users.

But some have suggested that companies like Twitter have more nefarious motivations for refusing to address Internet harassment than a simple lack of empathy for women. Video game developer Brendan Vance has suggested that Twitter “has far more to gain from permitting this sort of bullying” in terms of increasing user engagement “than it does from preventing it.” Twitter, Vance notes, postures as a “neutral third party” while simultaneously profiting both from its marginalized users and from the “thousands of people” who “enjoy harassing” them daily. By shifting the responsibility for ending harassment to its users by including a half-hearted block function, Twitter silently collects data and revenue from serial abusers of women and minorities while being able to claim that users can prevent harassment themselves. As games journalist Ben Kuchera puts it on Polygon, pointing toward Twitter’s “soaring stock price,” this is a “tacit statement that profit comes before people.” Jezebel’s editors too, had the impression that “Gawker’s leadership [was] prioritizing theoretical anonymous tipsters over a very real and immediate threat to the mental health of Jezebel’s staff and readers.”

Will this ever change? Will the Internet ever be safe for women? That depends on whether or not the men who own and operate its most popular services would be willing to accept a decrease in engagement from some users in order to make women feel more comfortable. As it stands, companies like Twitter are testing the limits of their majority female user base, simultaneously relying on women to power their services while implicitly requesting that they bear the brunt of harassment in order to accommodate abusive users.

Instead of removing the lions from the lion’s den, Internet companies continue to throw women into the lion’s den with little more than sharpened sticks to protect themselves. It might take us centuries to eradicate the sexism that powers the harassment of women on a cultural level. But Internet technologies like Facebook can be built in the short span of a few years. We may not be able to stop men from wanting to harass women but Internet technologies can easily be rebuilt. Maybe this time around, we could keep women in mind.