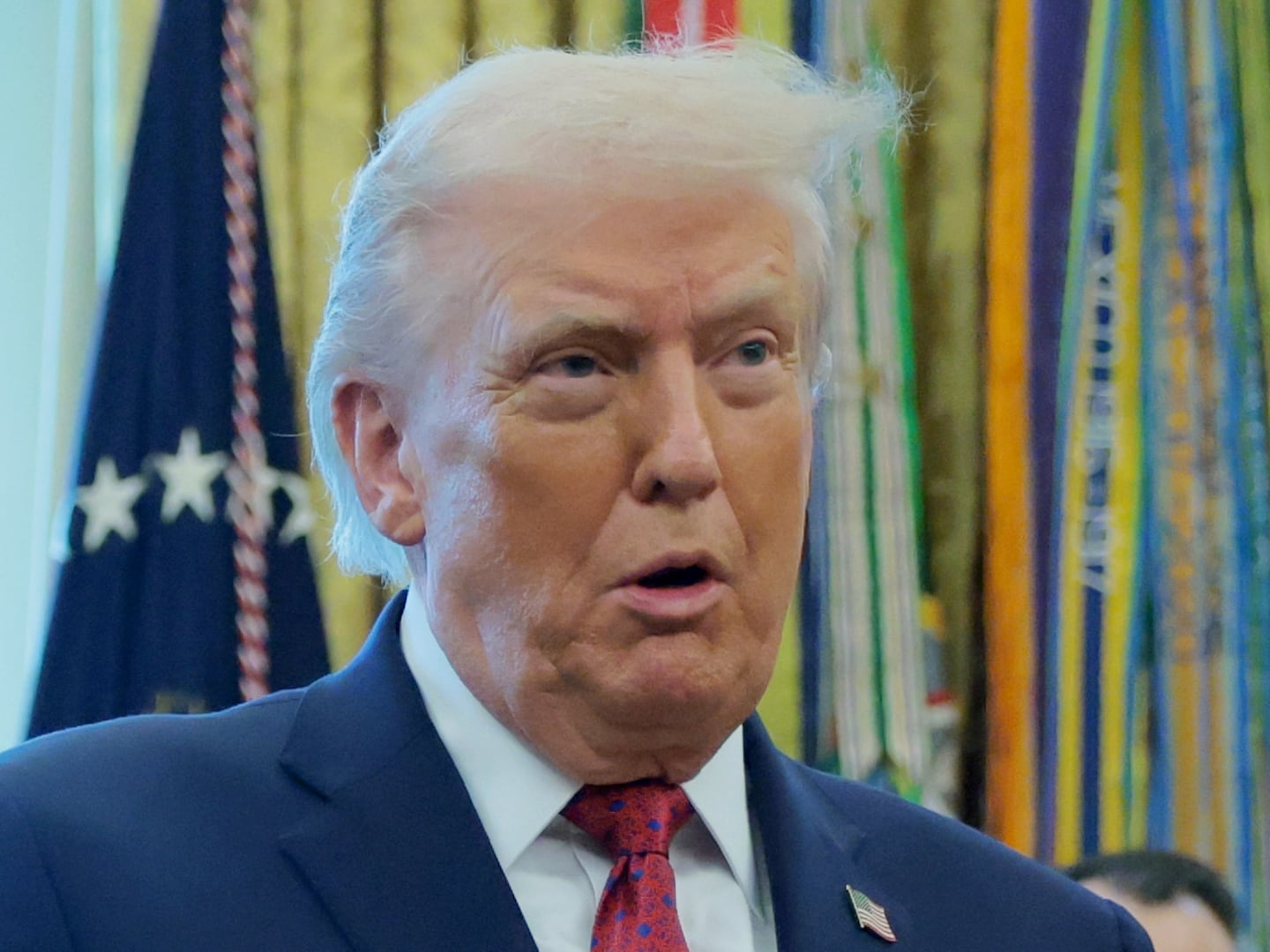

Thursday, August 28th, 2014, will go down as one of those rare moments when a President of the United States admitted publicly that the United States didn’t know how to deal with a major foreign policy crisis. When President Obama declared, “we don’t have a strategy yet” to confront ISIS, he was merely admitting what his Administration’s actions, or lack thereof, had made obvious.

Every President has to deal with a chaotic world that often seems focused on wrecking havoc on America’s self-interest. Presidents fail at foreign policy objectives more frequently than they succeed. Yet rarely have we seen a President so openly struggle with a declaration of American purpose and goals. Some of this is undoubtedly due to President Obama’s personality and the reluctance he shows in leading on many issues, foreign and domestic. But for the first time since JFK, we have a President who is not a product of the Cold War era—and the ramifications of that are profound.

Since the fall of the Berlin Wall, we’ve elected three Presidents. Clinton and George W. Bush were classic post-war baby boomers with a worldview formed by the Cold - and hot - Wars against communism. They were old enough to know “duck and cover” drills in schools and the formative figures of their political lives were key players in the Cold War era: President H.W. Bush, Ronald Reagan, Senator Fulbright of Arkansas. Both stumbled in their first presidential campaigns over issues of their service, or lack thereof, in the fight against communism.

Born in 1961, Barack Obama is our first president since JFK whose worldview was shaped in a non-Cold War crucible. Barack Obama never had to register for the draft and his seminal political experience were protests against apartheid, not the Vietnam War. “My first act of political activism was when I was at Occidental College,” he said in Senegal, on his 2013 trip to Africa. “As a 19-year-old, I got involved in the anti-apartheid movement back in 1979, 1980, because I was inspired by what was taking place in South Africa.”

At Nelson Mandela’s memorial service, the President reflected on how his involvement in anti-apartheid protests moment “ set me on an improbable journey that finds me here today.” Obama was drawn to and defined by causes of “social justice” in which nonviolence and appeals to decency were more than good intentions—they were effective tools. (The more violent aspect of the anti-apartheid movement was, safe to say, largely lost on Occidental College protestors.)

The language of the Cold War era dominated our politics for decades, giving politicians short hand clues to express a worldview clearly understood by their intended audience. When Ronald Reagan said, “Freedom is never more than one generation away from extinction,” he was encapsulating the dominant theme of post-World War American foreign policy: Peace Through Strength. One could agree or disagree with him, but Reagan was drawing on a clear set of assumptions of how the world worked.

These moral and strategic assumptions continued into the Bush 43 era even as the geopolitical landscape shifted. For Reagan the “evil empire” was the Soviet Union; for George W. Bush, there was an “axis of Evil.” The countries changed but evil was still evil. And by pronouncing other cultures and political systems “evil,” there was the assurance that America was good. Our goodness was defined, in part, by our willingness to confront evil abroad backed by military force.

As a post-Cold War figure who matured through “movements,” Barack Obama is drawing from a distinct tradition. He is clearly more comfortable talking about “justice” than “evil.” The “oppressed” to him are much more likely to be victims of society’s prejudice than communism. Some on the right argue that Barack Obama rejects the concept of America as a force for good but I think that’s a misjudgment. It’s more that he defaults to a fundamentally different test than his predecessors.

More often than not, Barack Obama defines America’s moral worth—our “goodness”—by comparing America’s past to some future in which the values in which he believes will be the norm. In that matrix, it’s not about us versus them—it’s about what we are versus what we can be. It’s us vs. us. America is “good” because we are getting “better.” We are at our best not when we fight the evils of the world, but the “injustice” of our society, primarily prejudice, for which there is an evolving test. He ran for office in 2008 opposed to gay marriage; now the issue is no longer gay marriage but “marriage equality,” and to be opposed to equality is a sign of prejudice. Justice demands equality; therefore justice demands gay marriage.

At the heart of this value system is an assumption that some essential elements of human decency push our society inevitably toward the values he shares. This premise is at the root of his frequent invocation of “the wrong side of history,” as has been oft observed, best in a brilliant piece by Jonah Goldberg.

The problems of applying a social justice framework to international crisis are not unlike applying a cold war formulation to, say, welfare reform. It just doesn’t work. After the horror of James Foley’s murder, President Obama said of ISIS: “People like this ultimately fail. They fail because the future is won by those who build and not destroy.”

A nice turn of phrase, but is it remotely accurate? Don’t maniacal movements like ISIS end only when good people rise up with the willingness to die to stop them? The President frequently touts his international culture background as proof of his understanding of other cultures. “I say this as the son of a Kenyan whose grandfather was a cook for the British, and as a person who once lived in Indonesia as it emerged from colonialism,” he said in Brussels when addressing the Russia-Ukrainian crisis. But it seems incredibly naïve and American-centric not to grasp that the Islamic fanatics of ISIS are very much about building—building a new world in their vision.

Most troubling, when America and the world are crying out for action and leadership, this homily is a call for inaction cloaked in moral smugness. If ISIS will “ultimately fail,” why the need to do anything? At best, it is what Jonah Goldberg deftly paraphrases as, ““You’re going to lose eventually, so why don’t you give up now.”

Even though Russia is now at war with a neighbor, the old Cold War formulations were indeed rusty and needed retooling, if not retirement. But as the world continues to defy the best wishes of President Obama, we’re seeing the limits of social justice tools brought to international crises.

Hillary Clinton correctly observed that “Don’t do stupid stuff is not an organizing principle” for a great nation. Neither is “people like this ultimately fail” a moral framework to prosecute a war against those who seek to destroy our values.