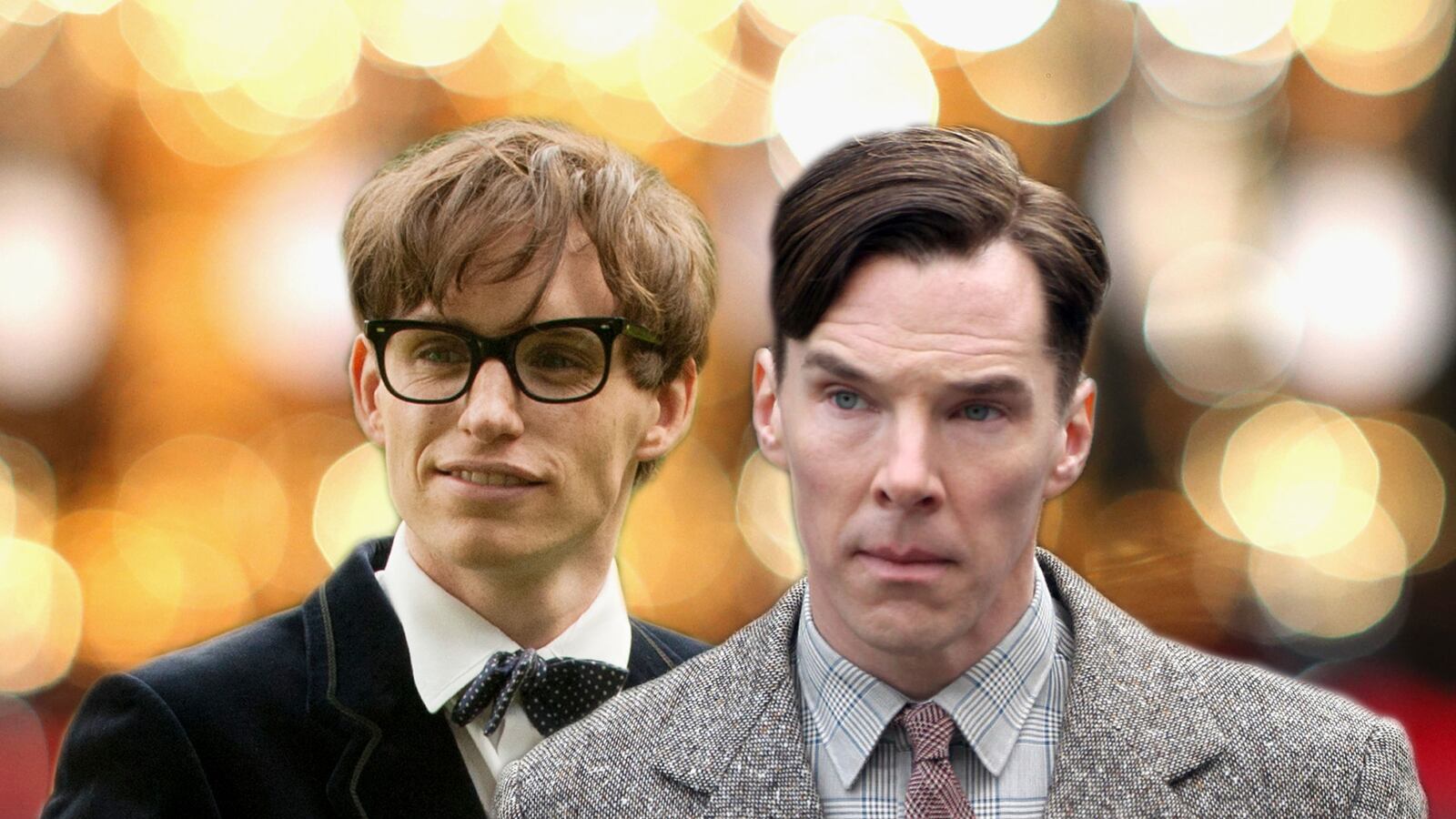

Cumberbitches and Redmaniacs, rejoice: You’ve got a pair of awards contenders on your hands—err… minds.

For the uninitiated, the Toronto International Film Festival is, aside from being one of the largest, most overwhelming film fests in the world, fertile ground for Oscar bait. The proof is in the poutine. American Beauty, Ray, Black Swan, and The King’s Speech, to name a few, all bowed in Toronto, and all received Academy Award wins for their stars. Most of the acting buzz at the ’14 edition of TIFF has concerned the performances of Benedict Cumberbatch and Eddie Redmayne in a pair of biopics that were practically stitched by hand in a clandestine awards factory beneath the Dolby Theatre.

Let’s start with the stronger of the two. In The Imitation Game, Cumberbatch portrays Alan Turing, a math prodigy and cryptanalyst who’s tasked by Prime Minister Winston Churchill with leading an elite group of code-breakers at Hut 8—a sector of Britain’s top-secret Government Code and Cypher School at Bletchley Park. Their mission is to break the Nazis’ Enigma code, their highly encrypted and presumably indecipherable method of communicating with their naval fleet via radio transmissions. “We’re going to break an unbreakable Nazi code, and win the war,” says Turing.

Directed by Morten Tydum from a screenplay by Graham Moore, the film chronicles Turing’s tragic life (via flashbacks) from his days as a bullied, reticent budding genius who falls for his boarding school classmate, to his World War II heroism, to the subsequent witch hunt in the days after the war that leads to his 1952 conviction on the grounds of “indecency” for engaging in a homosexual tryst—illegal in the U.K. until the Sexual Offences Act 1967, which decriminalized homosexual behavior. Turing was offered the option of two years in prison or oestrogen injections—tantamount to chemical castration. He opted for the latter, and two years later, took his own life by ingesting cyanide.

When we first meet Cumberbatch’s Turing, he’s supremely pretentious, brushing off his interview at Bletchley with Maj. Gen. Stewart Menzies with the self-assured riposte, “You need me more than I need you.” These early interactions, dismissing his peers and superiors with icy flippantness, recalls Jesse Eisenberg’s stellar turn as another Aspergers-y genius, Mark Zuckerberg in The Social Network. Unlike Fincher’s film, we’re granted context as to how Turing got this way, including being buried under the school floorboards and an early tragedy that informed his subsequent life and work. Confident, yet callow in the ways of man, he surrenders some of his obsessiveness and ego thanks to the tenderness of Joan Clarke (Keira Knightley), a fellow Hut 8 codebreaker whom he eventually proposes to—only to later rescind the offer and admit, in a particularly poignant scene, that he is gay.

The broad conceit here is, of course, that a man carrying a secret eventually solved the biggest secret of all, in what Churchill would later admit was the single biggest contribution to the British effort during WWII. And Cumberbatch, with his meek inflection, uneasy body language, and biting exterior, brilliantly captures the dichotomy of Turing’s confident, genius façade and his inner turmoil. When he breaks down to Joan during the latter stages of his court-ordered chemical castration, he’ll floor you.

And yes, while it’s a tad premature to drop the O-word in September, and you will inevitably see pieces in the coming months challenging the movie’s accuracy (the nature of his relationship with Joan, downplaying the efforts of his peers, and his being arrested for a gay tryst with a male prostitute rather than his boyfriend of one month, Arnold Murray), Cumberbatch’s powerful performance will inevitably draw comparisons to those Oscar winners in Shine, A Beautiful Mind, and The King’s Speech. Here, we have a tortured genius overcoming a disability who’s persecuted for his sexuality, which drives him to suicide; a tragic hero who hasn’t been given his due in the history books, and who was only granted a posthumous pardon by Queen Elizabeth late last year. All this—biopic, disability, persecution, tragedy—coupled with the fact that awards Svengali Harvey Weinstein is behind it, purchasing the U.S. rights to the film this year for a record $7 million at the European Film Market, should at the very least spell a nomination for the 38-year-old Brit. It’s the type of role Oscars were made for, and comes with the awards-ready tagline, “Sometimes it’s the people who no one imagines anything of who do the things that no one can imagine”—a line repeated to heartstring-tugging effect throughout the film.

Another role Oscars were made for comes courtesy of Eddie Redmayne in The Theory of Everything. The impressively-coiffed Brit plays renowned theoretical physicist and cosmologist Stephen Hawking, who fused the general theory of relativity and quantum mechanics to create groundbreaking studies on black holes and gravitational singularity theorems. At the age of 21, while studying cosmology at the University of Cambridge, he was diagnosed with motor neuron disease—or ALS—and given two years to live. Hawking slid into a deep depression, but was brought out of it by his girlfriend Jane Wilde (Felicity Jones) who proposed marriage and gave him something to live for.

Directed by Oscar winner James Marsh (Man on Wire) from a screenplay by Anthony McCarten, the film is more of a straightforward biopic that traces Hawking’s relationship with Wilde at Cambridge, his groundbreaking work in the field of theoretical physics, and his gradual physical decline—first losing his ability to speak, followed by near-complete paralysis. Though Hawking slowly loses control of his physical faculties, his mind remains sharp as ever, and Redmayne captures this with his boyish charm—the twinkle in his eye, and his self-effacing brand of humor. And the 32-year-old Brit, who coincidentally graduated from Cambridge himself with 2:1 Honours, does a superb job of navigating Hawking through his physical deterioration, including his slide into depression. The scenes between Redmayne and Jones where the latter party struggles to pull him away from the edge are masterful.

Of course, Redmayne also positively looks the part, and his portrayal of Hawking during the latter stages of ALS—the impaired speech and mannerisms—is spot-on.

Although it’s a role tailor-made for Oscar (see: My Left Foot), the overall quality of the film isn’t as strong as The Imitation Game, which may hurt its awards potential, and could leave Redmayne as the unfortunate sixth man out in the Oscar race, similar to John Hawkes for his moving portrait of paralyzed poet Mark O’Brien in The Sessions. It’s a very by-the-numbers biopic, and while it boasts two fantastic performances in Redmayne and Jones, as well as some impressive lensing courtesy of Marsh and his DP Benoit Delhomme, it seems narratively unimaginative. But all this, of course, remains to be seen.

An interesting thing to consider here is, if Cumberbatch and Redmayne indeed go head-to-head for the Oscar, it will not only pit two best friends against one another, but also two people who’ve played Hawking—as Cumberbatch did in his BAFTA-nominated turn in 2004’s Hawking. In fact, Cumberbatch recently told me that he received a funny text from Redmayne on the set of The Theory of Everything, which was also filmed at Cumberbatch’s primary school, Harrow.

“I played Stephen, as well,” Cumberbatch told The Daily Beast. “Eddie even texted me from Harrow, my old school, underneath a chalkboard with my name on it while he was dressed as Stephen Hawking. It was one of the most surreal, hall-of-mirrors experiences I’ve had of the past year.”

As far as their friendship goes, when he was asked whether or not he had groupies in a 2011 interview with The Guardian, Redmayne claimed he didn’t—and used his buddy Cumberbatch as an example.

“Benedict Cumberbatch is a mate of mine, and we did a charity show at the Old Vic together,” said Redmayne. “There was this group of women outside the theatre who name themselves ‘the Cumberbitches’ and follow him round the world. I have nothing like that. I really wouldn’t know what to do with the situation.”

Come February, it may be a horse of a different color.