Thank you, Stephen King. How many times have your stories kept me awake at night wondering, like a child in the dark, what monsters lurk nearby? You are one hell of a writer, and I think most of us in the business understand this: you think very carefully about our craft. So of course I read your recent interview with Jessica Lahey in The Atlantic on how you teach writing. And there, in paragraph seven, I found these lines:

“When it comes to literature, the best luck I ever had with high school students was teaching James Dickey’s long poem ”Falling." It’s about a stewardess who’s sucked out of a plane. They see at once that it’s an extended metaphor for life itself, from the cradle to the grave, and they like the rich language.”

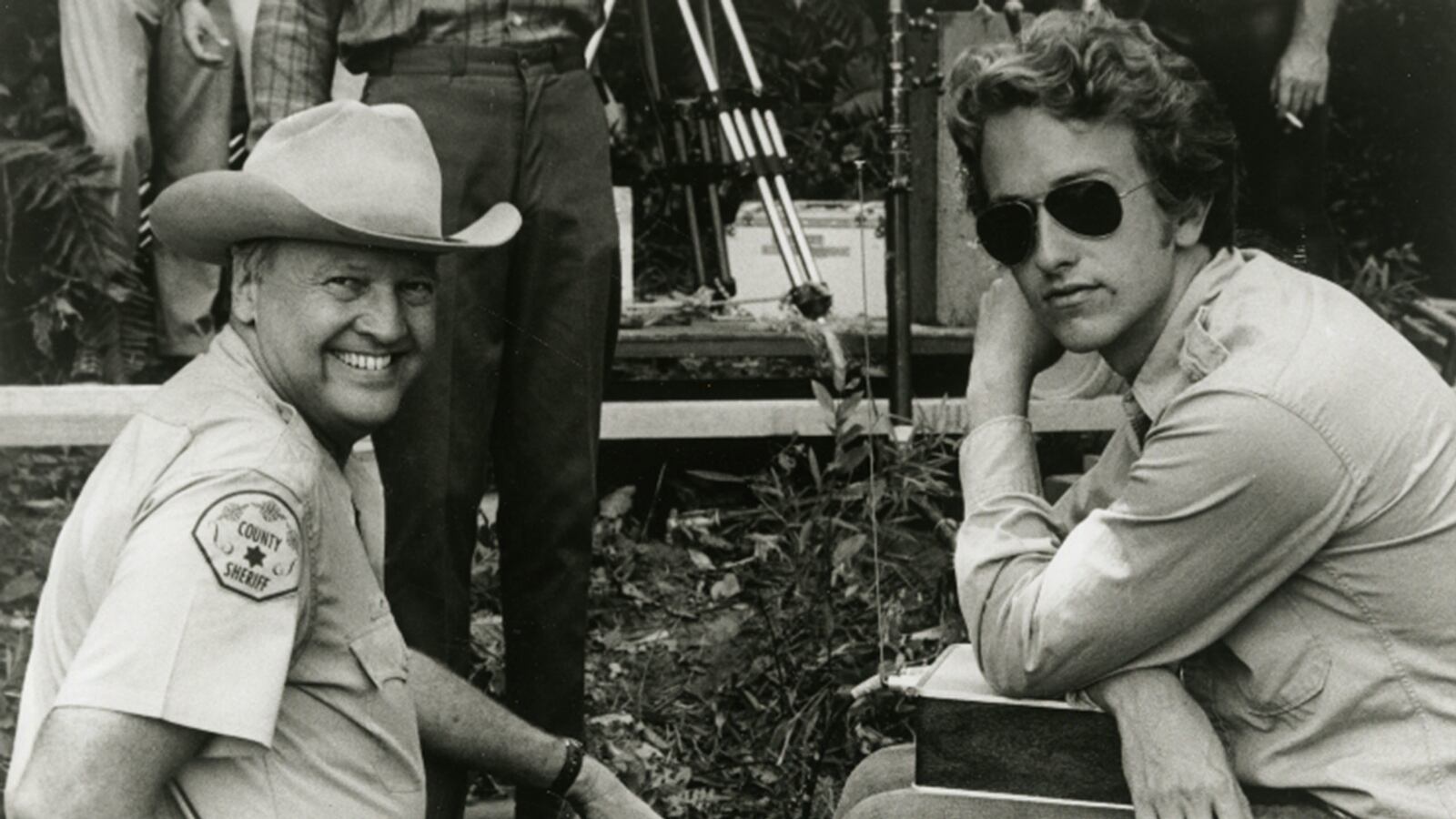

I’m not sure how many high school students these days have heard about my father, James Dickey, except (maybe) as the author of the novel Deliverance and the movie made from it. Like some perverse malediction from one of your books, the most-remembered line associated with him, “Squeal like a pig,” is one he didn’t write.

But what he did write with enormous passion and inspiration is poetry. And high school teachers today certainly could do worse than to teach “Falling.” The language, as you say, is rich. And as you know it’s more than that. To read that poem is to experience the exhilarating liberation of language that goes far beyond the obvious, that communicates in ways that we feel but cannot quite explain.

The language of “Falling” is what most writers, most lyricists, most rappers – hell, let’s say it – most poets are striving for. And it doesn’t bear excerpting. It’s not tweetable. It has to be read out loud in a rush of excited images linked and paced and plunging and diving until you are as breathless as that stewardess discovering life, embracing it, insisting on it in that fall to her death.

My father, too, was a teacher, and as it happens there’s a tape of the last class he ever gave. He was only 73 years old, but after a lifetime looking for inspiration at the bottom of a bourbon bottle (and sometimes finding it) the ravages of alcohol had taken their toll. He was sober in his last years, and brilliant – no, let’s use a favorite word of his: effulgent -- but he was dying before our eyes. So when he sat with the students who had come to his house to try to learn something about writing, he put aside questions of grammar and punctuation and metaphor and simile, which are so important to us all, and he told them in his warm Southern voice something he thought might – just might – change their lives.

“Invent,” my father told those students. “Invent is the guts of it. ‘To invent.’ You can say as much as you like with stuff you know. But don’t be confined to it. Don’t think about – honestly – don’t think about telling the truth. Because poets are not trying to tell the truth, are they? They are trying to show God a few things maybe he didn’t think of. When we sit down to write we are absolute lords over our material. We can say anything we want to, any way we want to. The question is to find the right way, the best way to do it. This is what we are going to be looking for.”

I remember the first time I heard that tape. As I wrote in my memoir about my father, I was with my brother, Kevin, and one of our closest friends in a car. We had been making funeral arrangements. The poet-teacher-father’s voice was coming to us through the stereo.

“This is going to take us through some very strange fields, across a lot of rivers, oceans, mountains, forest. God knows where it will take us,” my father said. “That is part of the excitement of it, and the sense of deep adventure. Which is what we want more than anything. Discovery. Everything is in that.”

Then his tone changed a little. “With my current physical shape,” he said almost casually, “this will almost undoubtedly be my last class forever.” He wanted the students to pay close attention.

“Flaubert says somewhere that the life of a poet is a hell of a life, it is a dog’s life, but it is the only one worth living,” my father told his students. “You suffer more. You are frustrated more by things that don’t bother other people. But you live so much more. You live so much more intensely and so much more vitally. And with so much more sense of meaning, of consequentiality, instead of nothing mattering. … That is what is behind all the drugs and alcoholism and suicide – insanity, wars, everything – a sense of nonconsequence. A sense that nothing, nothing matters. No matter which way we turn it is the same thing. But the poet is free of that.”

“For the poet, everything matters, and it matters a lot. That is the realm where we work. Once you are there, you are hooked. If you are a real poet, you are hooked more deeply than any narcotics addict could possibly be on heroin. You are hooked on something life-giving instead of destructive. Something that is a process that cannot be too far from the process that created everything. God’s process.

“You can say what you can of God. I don’t know what your religion might be. You can say what you want as to whether this is a chemist’s universe or a physicist’s universe or an Old Testament, New Testament God’s universe. Whatever you might want the deity to be.

“Those are things that he might be. What this universe indubitably is is a poet’s universe. Nothing but a poetic kind of consciousness could have conceived of anything like this. That is where the truth of the matter lies. You are in some way in line with the creative genesis of the universe. We can’t create those trees or that water or anything that is out there. We can’t do it. But we can re-create it. We take God’s universe and make it over our way. And it is different from his. That is where our value lies. Not only for ourselves, but for the other people who read us. There is some increment there that we make possible that would not otherwise be there.

“I don’t mean to sell the poet at such great length, but I do this principally because the world doesn't esteem the poet very much. They don’t understand where we are coming from. They don’t understand the use for us. They don’t understand if there is any use. They don’t really value us very much. [But] we are the masters of the secret, not they. Not they. Remember that when you write.”

Thank you again, Stephen King, for understanding, and for remembering.