Former sex crimes prosecutor Lisa Mendelson Friel—who was hired 11 days ago by embattled National Football League Commissioner Roger Goodell to help clean up the mess he’s made—loves and reveres the New York Giants.

She’s the sort of fan who turned the den of her Brooklyn home into a shrine (painting it Giants blue and red and decorating it with team paraphernalia and a life-size wall-hanging of Eli Manning), boasts season tickets that have been in her family for more than 60 years, and cheers her lungs out at every game at MetLife Stadium in the New Jersey Meadowlands.

“She’s a rabid Giants fan,” says Friel’s former boss, Linda Fairstein, the famed New York prosecutor-turned-crime novelist. “I can be sitting at home staying good and toasty, watching a game, and she’s out there in all kinds of weather,” Fairstein says. “She knows football inside-out.”

The fate of football, and especially of NFL Commissioner Goodell, has been up for grabs for the past three weeks, ever since TMZ Sports splashed the grainy surveillance video of Baltimore Ravens running back Ray Rice slugging his fiancée/now-wife Janay Palmer inside an elevator last February at an Atlantic City casino.

Goodell had already been under fire for giving Rice an astonishingly lenient two-game suspension—this, five months after TMZ posted an initial video showing Rice dragging the unconscious Palmer outside of the elevator like a sack of potatoes. A widely published police report of the brutal attack left no doubt as to what had occurred.

Other incidents of domestic violence involving NFL players only increased the heat on Goodell, who apologized for his mishandling of the Ray Rice affair, and suspended him indefinitely from the game, while claiming unconvincingly that nobody in his office had seen the latest damning video until TMZ released it on Sept. 8. Goodell was suddenly a figure of near-universal scorn. His disastrous televised news conference last week made things worse.

Here’s the question for Friel, now that she’s on the NFL payroll: Can she help repair the damage in the court of public opinion?

Friel—who was “inundated with requests from the media to interview me,” according to a statement she issued Sept. 17, two days after Goodell announced her appointment—hasn’t yet granted an on-the-record press interview, and didn’t agree to one with The Daily Beast. However, in the same statement, she described her “focus” as “getting up to speed with the details of pending incidents, the Personal Conduct Policy, the more recently announced domestic violence and sexual assault enhancements to the Policy, and of course the Collective Bargaining Agreement that the League has with its players in order for me to be able to give Commissioner Goodell the best advice I can.”

In a paean to her astronomically compensated ($44 million-a-year) client, Friel added: “I have met with him a number of times over the last week and I can say without reservation that he is deeply committed to getting this right going forward, and I am equally committed to helping him do so.”

According to a knowledgeable source, Friel has known Goodell professionally for a few years. She was hired to do some work by the NFL after visiting the commissioner in his office in 2011. Now a private attorney and executive for a corporate consulting firm, she has worked with various NFL officials in the past, and two years ago she gave a talk on sexual violence and abuse to the NFL/NCAA Coaches Academy—a group of aspiring football coaches. She is an internationally acknowledged expert in the issue.

Back in the Manhattan District Attorney’s office, Linda Fairstein had spotted Friel as a courtroom talent in the mid-1980s, and recruited her to the nation’s first prosecutorial squad dedicated to fighting sexual crimes when she was a young assistant district attorney.

In a rare interview five years ago, Friel recalled trying her first rape case in 1986. “She was so much like me,” she said about the victim. “We were the same age. She was a Penn graduate. I was Dartmouth. I identified with her.”

When she won a conviction, Friel recalled, “Boy, did I ever feel I made a difference. From that day I was hooked. I realized this was the perfect job for a people person like me.”

Legendary Manhattan DA Robert Morgenthau, 95, who stepped down five years ago after 35 years in office, hired Friel in 1983 as a recent graduate of the University of Virginia School of Law after she had earned a history degree at Dartmouth College, Class of 1979.

“She gets people to tell their stories in difficult cases—and sex crime cases are often very difficult,” says Morgenthau, who these days hangs his hat at the New York law firm Wachtel, Lipton, Rosen & Katz. “She was very good at getting people to put their confidence in her, and she was also very good at figuring out if somebody was a phony.”

With Morgenthau’s approval, Fairstein named Friel her deputy in 1991, and in 2002, when Fairstein retired, tapped her to succeed her as chief of the Manhattan DA’s 40-lawyer Sex Crimes Prosecution Unit.

During her law school years and her rise through the ranks, Friel had found time to be married and divorced twice—the first time, briefly, to a college sweetheart and fellow law student; the second time to a colleague in the DA’s office, chief of the trial bureau James Friel, with whom she had two sons and a daughter, now all adults. After their split, Jim Friel died shockingly at age 48 of bacterial meningitis.

“It was very hard,” Friel said in the 2009 interview, recalling the aftermath of the tragedy and her status as a single mom raising three young children. “The kids and I learned to talk a lot after Jim’s death. We still do. It made us very close as a family.”

And yet, according to friends and colleagues, Friel’s beloved Giants were seldom far from her thoughts. At 57, Friel seems to have an almost spiritual connection to her cherished team and, by extension, professional football—a passion she picked up from her much-loved late father, Robert Mendelson, the owner of a ladies’ garment manufacturer on Seventh Avenue. This makes her in some ways the perfect person to help the NFL recover from its self-inflicted wounds and get its act together.

Her private-sector experience for the past three years running the sexual misconduct consulting & investigations division of the T&M Protection Resources corporate security firm, as well as her three-decade track record as a state litigator, and administrator—with the job of obtaining justice for rape, human trafficking and sexual abuse victims in often-horrific and emotionally wrenching cases—potentially give her the tools to turn over rocks and uncover whatever violent, misogynistic underside exists in the $10 billion-a-year, 32-team pro football business. She also acquired political and policy-making skills as a frequent visitor to New York’s state capital, Albany, where she testified at committee hearings and worked to reform the criminal laws. With State Sen. Liz Kreuger, who is also a social friend, she toiled in 2006 to remove the statute of limitations on rape charges, which had previously been a mere five years.

Along with two other high-profile women that the NFL quickly hired this month in its public relations battle against sexual assault and domestic abuse—Jane Randel, co-founder of the domestic abuse opponent “NO MORE,” and anti-domestic violence professional Rita Smith—Friel is being paid to help team owners and league executives avoid terrible misjudgments like the Ray Rice case and other recent headline-making incidents, formulate a consistent personal-conduct policy for players and staff, and presumably bail the much-criticized Goodell out of a job-threatening crisis.

“She’s very, very thorough and tenacious,” says Katherine A. Lemire, a former federal prosecutor who had toiled in the sex crimes unit and was counsel to New York Police Commissioner Raymond W. Kelly before launching her own eponymous investigations firm. “If you want to get to the facts, and make sure the right rules are being followed at the NFL, Lisa is your woman. She’s not going to mince words and compromise. She’s no-nonsense.”

Unlike the vividly quotable Fairstein, who has clearly enjoyed her celebrity as a crime-fighter, author and television personality, Friel has mostly shied away from mingling with the media—with a couple of notable exceptions. One was the extensive interview for a cover profile in the July/August 2009 Dartmouth Alumni Magazine; and the other was her participation in a June 2011 HBO documentary, Sex Crimes Unit, which ended up playing a controversial role in her abrupt departure from the DA’s office a couple of months later.

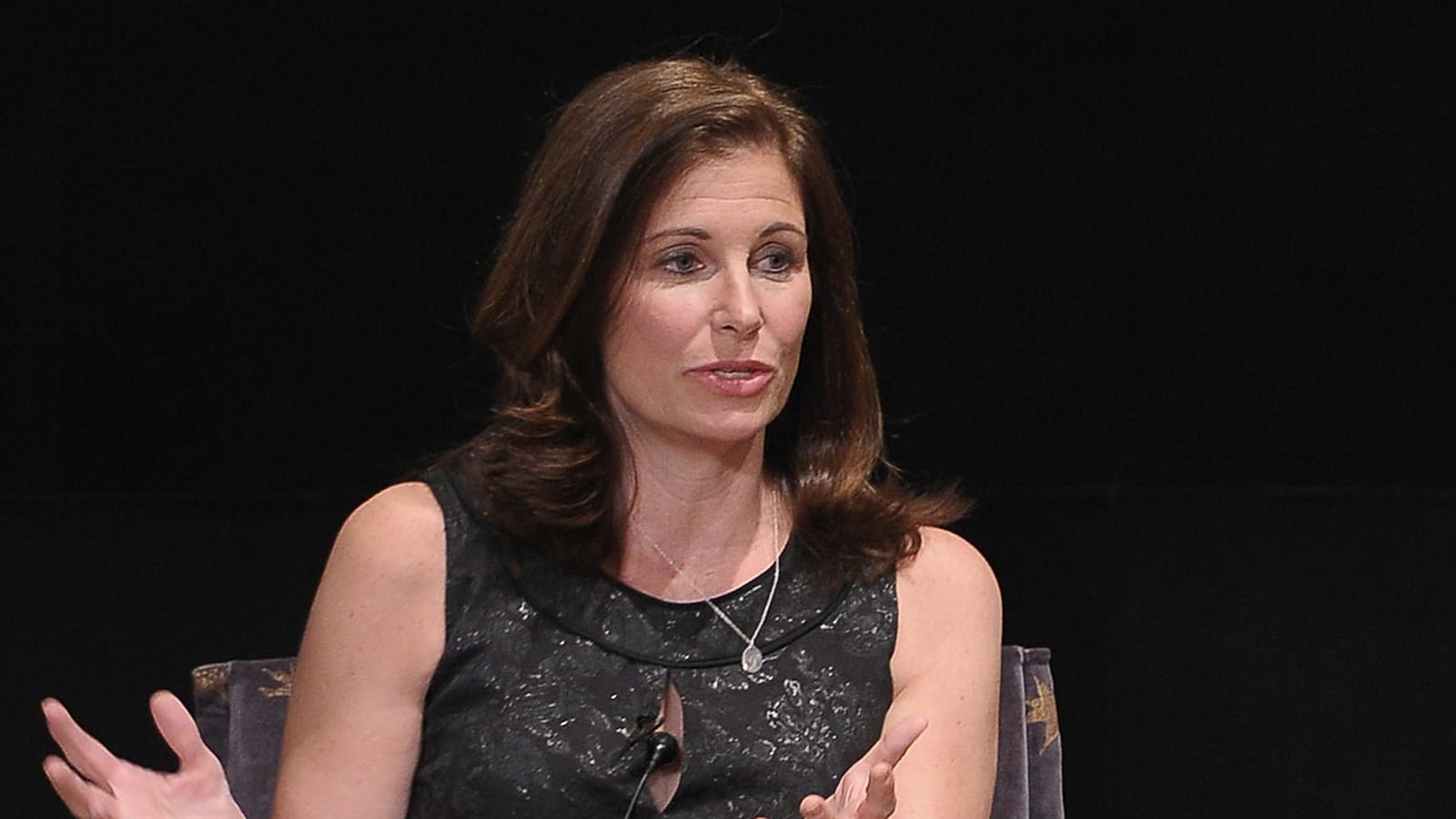

Morgenthau—who was proud of the groundbreaking work of the sex crimes unit that he established—had finally agreed to cooperate with documentary filmmaker Lisa F. Jackson after she made multiple requests for behind-the-scenes access over a period of several years. By late 2009 she had shot 80 hours of film starring the petite, physically fit, brown-haired Friel (a high school and college basketball and tennis player who took up golf after multiple knee surgeries). Also featured was Friel’s staff of mostly female prosecutors gathering evidence, wolfing down sandwiches, talking about their lives and work, and trying sexual assault cases.

In a time of rampant cynicism about government bureaucracy, the documentary offered a moving and reassuring portrayal of dedicated, caring public servants—Friel not least among them—doing good work on behalf of the citizenry.

But according to multiple sources, newly elected Manhattan District Attorney Cyrus R. Vance Jr. was not happy with Sex Crimes Unit. He first learned of the project after he took office in January 2010, after it was nearly completed. He felt blindsided by this potential disruption of his newly configured DA’s office.

Jackson acknowledges that had the reigning DA been Vance instead of Morgenthau, the film probably wouldn’t have been made. Although he initially allowed Jackson to film him at work, Vance refused her permission to include the footage, while his staff vetted the movie frame by frame and demanded that Jackson delete scenes that they said could affect ongoing cases.

Indeed, former NYPD cop Kenneth Moreno, who in 2011 was prosecuted by the sex crimes unit in the alleged rape of an inebriated female fashion executive, and served nine months at Riker’s Island on a conviction of official misconduct, recently filed a $175 million lawsuit against Vance, the city, and various current and former DA staffers, including Friel, on the theory that outtakes from Jackson’s movie demonstrate prosecutorial misconduct.

When Goodell announced Friel’s appointment, Moreno’s attorney, former New York cop Eric Sanders, took the opportunity to tweet: “How can the @nfl hire Lisa Friel, she was implicated for prosecutorial misconduct in the Moreno alleged rape case?” The presiding judge in Moreno’s trial, Gregory Carro of New York Supreme Court, as well as two appeals courts, had ruled that the outtakes were immaterial and, besides, showed no such thing.

Also in the headlines at around the same time as the documentary’s release was Friel’s role, or lack thereof, in the decision-making process of Vance and his team that led to an embarrassing collapse in the prosecution of International Monetary Fund chief Dominique Strauss-Kahn on charges of sexually assaulting a hotel maid.

Friel, a Morgenthau loyalist, had clashed with Vance’s senior staff over the strategy and tactics of not only the DSK case but several others since Vance assumed office in January 2010. Different from the Morgenthau days, Vance had installed a senior staffer to supervise Friel and her unit.

According to people with knowledge of the situation, Friel had urged a methodical and potentially time-consuming investigation of the alleged DSK assault instead a quick indictment driven by the news cycle. Her advice was rejected. When it was discovered that the French politician’s alleged victim, Guinea native Nafissatou Diallo, had lied not only on her political asylum application but, worse, to the grand jury, her credibility was destroyed and the case imploded.

Friel’s friends believed she could have prevented the debacle by questioning Diallo before her grand jury appearance and getting her to admit the lie on her asylum application; they also believed members of Vance’s inner circle were setting her up to take the fall. Within a few weeks, Friel had decided to leave her challenging and rewarding 28-year-old vocation and take a job in the private sector. Vance’s communications office didn’t respond to phone messages from The Daily Beast.

“I think she felt misportrayed,” says CNBC producer Shari Lampert, Friel’s close friend since their childhood in the comfortable suburb of Haworth, New Jersey. “I think after giving so much of her time and energy to public service for so long, she was hurt at how it ended.”