One afternoon in the spring of 1970, my phone rang. It was Klaus Voormann. I hadn’t spoken with Klaus in quite some time and was curious as to why he was calling. The last time we spoke was nearly a year ago, when he had played bass on my first solo album Extraction. At that moment, I had no idea that what I was about to hear would soon alter the direction of my life.

“Klaus, how are you? It’s been a while.”

Before I could say anything else, he quickly replied, “Gary, I’m in the studio with George Harrison. Phil Spector is producing George’s new album and wants an additional keyboard player for the song they’re working on. Can you come to Abbey Road Studios now, as George is keen to get started?” The import of those words resonated through my entire being. I was a huge Beatle fan and especially loved George’s amazing track “Within You Without You” from Sgt. Pepper, with its East Indian flavors.

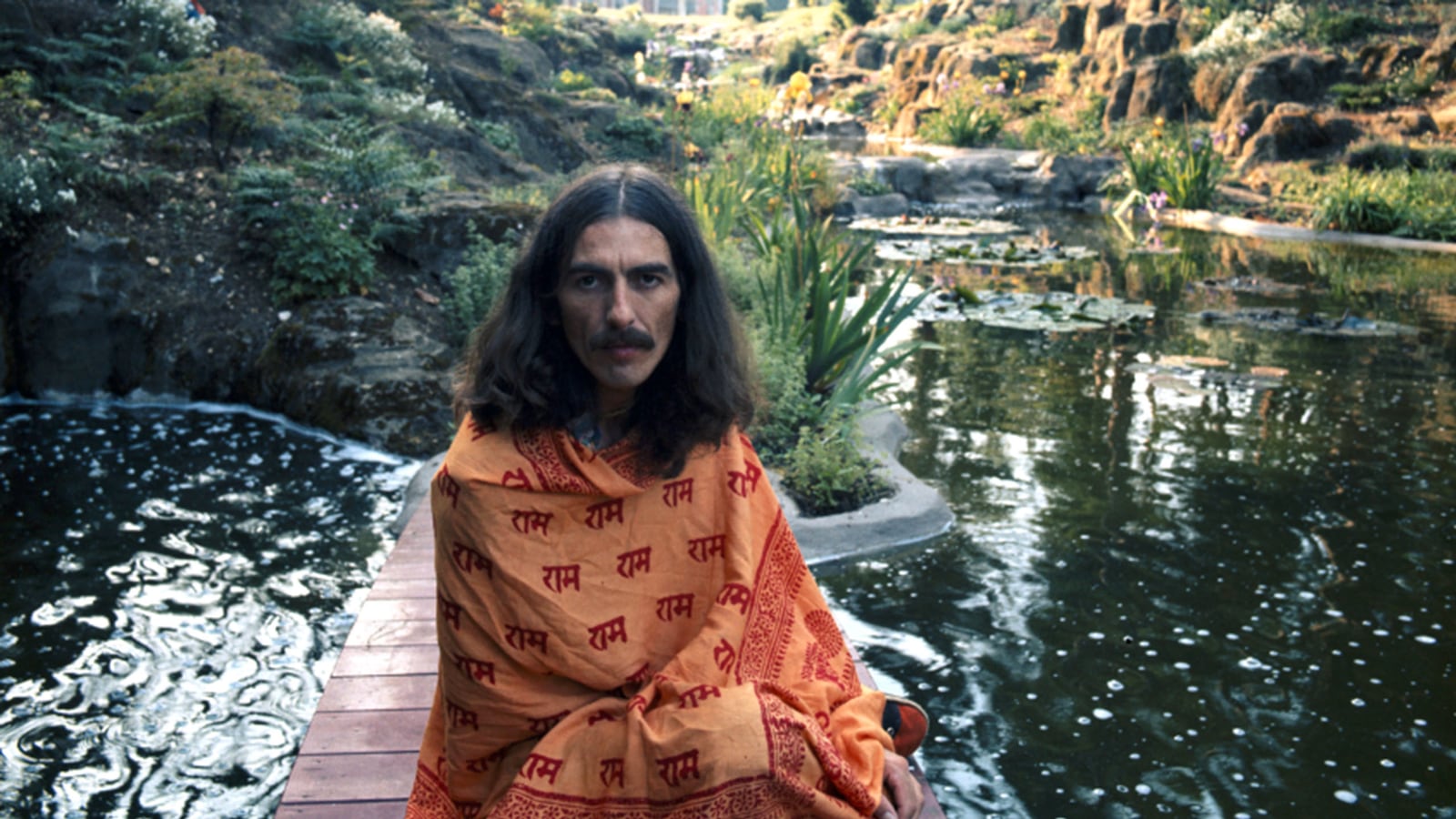

One half hour after I’d received the call I found myself walking into the studio where the recording session was taking place—the same studio where the Beatles had recorded most of their music—and Klaus warmly greeted me. I immediately spotted George Harrison at the other side of the studio; we made eye contact, he smiled, and walked over to greet me. He was dressed in traditional Indian white pajamas and dark brown sandals. His long, straight, dark brown hair was parted in the middle and reached halfway down his back; he had a fairly long beard and mustache that covered a good part of his face. I could smell the patchouli oil he was wearing as well as the incense that was burning in the studio.

His brown eyes were penetrating yet peaceful, and he immediately disarmed my nervousness with his gentleness. As he shook my hand and graciously introduced himself to me, all the initial apprehensiveness I had been feeling suddenly vanished. I felt in my heart that I was meeting an old friend that I hadn’t seen in years—or maybe lifetimes.

He introduced me to the other musicians playing on the track, including Ringo, Eric Clapton, Billy Preston, Klaus Voormann, Jim Gordon, and Badfinger. The group had been rehearsing the song “Isn’t It a Pity” when I arrived. George took his acoustic guitar and began showing me the chord changes, which I nervously wrote out on a chord chart. I was making a fair amount of mistakes trying to learn the arrangement while playing along with the band. After a little while, the red “record” light in the studio came on and I still wasn’t quite sure of the structure of the song. Then the worst that could happen happened. Producer Phil Spector’s voice rang out from the control room into the studio where all the musicians were: “Wait a minute, wait a minute; who’s that on the Wurlitzer piano making all those mistakes?” Devastated and utterly embarrassed, I meekly raised my hand. and said, “Sorry it’s me, Gary. I’m still learning the structure of the song.” George immediately walked over to me and said consolingly, “Take all the time you need, we’re in no rush.” He was so kind at that moment; I immediately felt a rapport with him.

I had really never met anyone quite like George before; he didn’t seem to be on some huge ego trip like other artists I had met over the years. His aura was calm, and his being exuded a subtle spiritual magnetism. Yet, at the same time, he was someone who was very focused in the here and now.

While we were recording the song, George played his guitar and sang along as a guide to give the other musicians a feel for the different parts of the track, along with the dynamics. After several takes, we all went into the control room to hear what we had done. George listened intently and made his comments to Phil and the rest of us, and we returned to the studio for more takes until he was satisfied. I could immediately tell that he liked simplicity in his backing tracks to allow the song to shine through without competing with the music of the track.

When he first played “Isn’t It a Pity” for me, the song we would be working on that day, I silently marveled how beautiful his writing was, both melodically and lyrically: “Isn’t it a pity, isn’t it a shame, How we break each other’s hearts and cause each other pain, How we take each other’s love without thinking anymore, Forgetting to give back, now isn’t it a pity.” So simple and yet moving, the song seemed to take its expression from the peacefulness of his soul.

Despite being intimidated at first, I was quickly disarmed by George’s simplicity and kindness. Eastern philosophy teaches that we frequently are drawn into circumstances where we will meet our close friends from previous lives so that the relationship can progress. The soul immediately recognizes that person and the relationship picks up from where we left off at the time we were separated by death. Friendship is the highest expression of love, whether it is expressed between husband and wife or guru and disciple, and mutual love for God is one of the highest forms of friendship. It is natural and created without our willing it so and without compulsion. It is perfected over many incarnations until it is transformed into pure divine love in its highest expression. With George I had that intuitive feeling of recognition initially, and years later when I became steadfast on my spiritual path, I realized I must have known him before and that he was the instrument God had chosen to introduce me to my spiritual path and guru.

At the end of the day, when we got the take both George and Phil liked, I walked up to George and thanked him for giving me the opportunity to play on his album. “You did well. Come on back tomorrow around noon and you can play on another track.” I couldn’t believe he was asking me to return, especially after my fumbling through the beginning of the session in front of Phil and all those incredible musicians. I got into my car and just sat there in the balmy London night replaying the events of the day in my mind. It was like waking from a beautiful dream and feeling so elated and special. But it didn’t end there. I wound up playing keyboards on the entire album, aptly named All Things Must Pass, which became the biggest solo Beatle album ever, producing several number 1 hits worldwide. This was the beginning of a very deep and meaningful relationship that endured until George’s passing in 2001.

WE BECOME FRIENDS

The recording sessions for All Things Must Pass, a double album, lasted for more than a month. Every day, I drove from my flat in Mayfair to Abbey Road in joyous expectation of what magic I would be participating in that day. I was feeling really good about the keyboard parts I was coming up with at the sessions, and George was giving me positive feedback and encouragement as well. I had been emotionally and creatively deeply invested in my first solo album, Extraction, and its failure had been a huge blow to me. But I never lost faith in myself. I have always believed that when one door closes another one opens, so being asked by George to play on his entire album couldn’t have happened at a better time.

As time went on, the sessions became smaller and more intimate, moving away from the large production concept Phil had created for some of the earlier tracks we had recorded. The rhythm section shrank down to George, Klaus Voormann or Carl Radle on bass, Ringo or Jim Gordon on drums, Eric Clapton, and me on piano, organ, Wurlitzer piano, or harmonium. I was enjoying the intimacy of that configuration a lot more and began to feel like I was part of a band of truly great musicians who had already made musical history. “Some of the songs on this album were songs that never made it on Beatle albums,” George remarked to me one day before a session. I felt very touched and honored hearing this, knowing that I was coming to the studio each day and playing an integral part in his first solo album. Beatle politics were such that Lennon/McCartney had dominated the real estate of the songs on their albums, one of the reasons George quit the band in the first place. Not only that, but I feel his writing had gotten better over the years, culminating with his two brilliant tracks on Abbey Road, “Something” and “Here Comes the Sun.” He needed an uninhibited fresh outlet of expression, and this new solo album provided that.

One afternoon, as we were about to start a new track, John and Yoko, both dressed in black, walked into the studio. George’s face and demeanor immediately changed and he grew very silent and seemed agitated. This was the first time I saw that side of him. His vibe was icy as he bluntly remarked, “What are you doing here?” It was a very tense moment and I wasn’t sure if his question was directed to John or Yoko. But George’s look spoke volumes. Five minutes later they both left. This occurred at a time when there were strained relations between Yoko and George, though that mellowed out as the years passed by. It was still early on in our relationship, and I didn’t know him well enough to say which of the two he was reacting against at the time, but in retrospect I feel that he was reacting against a threat to his newly found independence.

Several years later, I received a call from Mal Evans, the Beatles road manager: “Gary, it’s Mal here. John is starting his new album and wants to know if you’ll play keyboards on it.” He gave me the dates, and when I looked at my calendar, I realized that the sessions were right in the middle of a Spooky Tooth tour I was committed to that had already been booked. Spooky Tooth had reformed quite a while before I received the call and were touring quite often. “I can’t do it, Mal,” I finally answered. “I’ll be on tour and can’t get out of it.” The album became his classic work Imagine, and I was truly disappointed at not being able to play on it. Several years later I met George in New York while he was in the middle of his Dark Horse tour. I was in his suite at the Plaza Hotel with my manager Dee Anthony’s daughter, Michelle, when in walked John, followed by Bob Dylan. George introduced us to Bob and John, and John warmly shook my hand and told me he liked my keyboard playing on George’s albums. I was honored and deeply touched by his kind words. George then began discussing the details of the concert he would be doing at Madison Square Garden the next day and the possibility of them all playing together. Over the years of my conversations with George, I saw that he had deep respect for John and loved him as a brother. I remember speaking with him shortly after John was killed. He was devastated.

To me, the quality of songs on All Things Must Pass was nothing short of amazing. Each time I entered the control room to start a new track, I would wonder what treats were in store. George would take out his lyric book and acoustic guitar and play us the song we would be working on that day. He loved simplicity in his musical arrangements, which allowed his lyrical message and melodies to shine through. Occasionally, he’d even walk up to me while I was playing piano and suggest a change in what I was playing; when I made the change, he’d beam back a big smile. Sometimes I would just close my eyes and take in the experience of simply listening to this master songwriter play yet another of his gems. Many were true masterpieces, but what really took me back were his unusual lyrics. Songs like “My Sweet Lord,” “Beware of Darkness,” “Art of Dying,” and “Hear Me Lord” had spiritual messages, something I had not heard before in pop music—especially to the degree that he used them. He was breaking new ground as an artist to an even greater degree than he had done in the past, and his slide guitar playing throughout the album set a new trend among guitarists throughout the world. He had become a guitar player’s guitarist. There was a feeling of sweetness and a haunting beauty in both his personality and his music.

The control room at Abbey Road became transformed into George’s sanctuary, with incense burning alongside the photos of Indian saints that he placed on the mixing console. In all the recording I had done up until that time, I’d never experienced anything like this: the vibe he created was profoundly peaceful. That, combined with the incredible group of musicians he had assembled, added yet another level to the overall experience during the sessions. As the project progressed, I felt a subtle change happening to me, as though I was picking up some of his spiritual magnetism. He saw that I was fascinated with Indian culture, especially the pictures of the saints he brought in, and he began to give me spiritual books to read, mostly about Lord Krishna and the Krishna Consciousness Movement. Every few days he would give me a fresh supply of incense he got directly from India, fragrances I had never before experienced. I began to follow George’s example and ate mainly Indian vegetarian food during our meal breaks. London is known for its great Indian restaurants, and every night the food he ordered into the studio was amazing—a veritable feast. During those breaks, he would talk to me about Indian philosophy, and I began to enjoy the breaks as much as I did the playing. Although at times he could be reflective and withdrawn, to me he definitely wasn’t the “quiet Beatle,” as the media portrayed him. Once he got on a roll, he didn’t stop talking until he finished his story. At his memorial service, Eric Idle said, “We all know that the press called him the ‘quiet Beatle,’ but for those of us who knew him well, we knew different. Once he started talking he never stopped.”

He also had a great sense of humor. Many times as we were listening to a playback in the control room, he would jump out of his chair and start dancing around like a wild man. At other times, he would make up some moves and play “air saxophone,” as though he was a sax player in Little Richard’s band. But most of all he loved Monty Python and would regularly repeat their hilarious sketches verbatim. It was all part of his personality to laugh and joke around and then pick up a guitar from his incredible collection and launch into a beautiful song that would make you cry. His style of playing was truly unique; it didn’t take me long to realize that all those great guitar solos and intros that started many Beatle’s songs were his.

A few weeks after the album was done, the phone rang and it was George. “Would you like to come over and see my new pad this weekend?” he asked. “I’m still in the process of redecorating it but you’re welcome to come by for tea.”

Very pleasantly surprised, I quickly responded, “I would love to see your home, George.” After the conversation ended, I put the phone down, feeling both nervous and extremely curious as to what was in store for me. “George’s home has to be amazing,” I mused. A few days later on a beautiful sunny day in early summer, I left my London flat and began my sojourn to his home in my yellow Triumph Spitfire convertible. It was about thirty miles due west from London in the English countryside, and it took me more than an hour to get there. Friar Park, the name of his newly acquired residence, was a palatial mansion built in the late nineteenth century by an eccentric barrister named Sir Frank Crisp. After driving up a rather long, winding driveway past a beautiful lake with waterfalls and groups of floating lotus flowers, I made a made a turn and came in full view of the home, or should I say Gothic castle. It was staggering.

“Come on down to the garden, we’re having tea,” George said after greeting me. I followed and was soon sitting at a quaint table with chairs facing the lake. George had to go inside to take a phone call so I sat feasting my eyes on the beauty of the surroundings. Soon, a tractor lawnmower headed toward me, its driver looking straight ahead as if I wasn’t there. Without turning his head, he drove slowly past me with his arm extended, handing me a joint. I thought the gesture was so far out in this Victorian context, but I refused his offer for fear of getting wasted and maybe starting to speak in tongues!

After tea, we went inside to view the work that was being done. He was living with his first wife, Pattie, in one of the apartments upstairs while the work was being carried out in the main part of the house. The color combinations for the walls and ceilings of each room were unusually beautiful: all of them were custom colors he carefully created himself. I vividly remember one of the rooms having deep, rich tan walls bordered by a turquoise crown molding wrapping the entire room where the walls and the at least sixteen-foot ceiling intersected; one of the small horizontal lines on the molding was painted silver, which tied the entire color scheme together in a striking way. George loved to select colors from nature, whether they were from wildflowers or even shades of green from unusual plants—tropical or otherwise. There was no room in his personality for “that’s good enough”; he carried his ideas to their unique fulfillment. He was probably one of the most creative people I’d ever met. He was not only an amazing musician, but an incredible designer as well. Each item, brought from India or other places in the world he’d visited, was meticulously placed throughout the estate. I remember him buying tiles in Portugal, during one of our vacations together, that he later made into a mural with the Hare Krishna mantra incorporated into the design. Tile work in the bathrooms, furniture, and artwork on the walls all flowed together and carried his creative touch. Each room wound up being a work of art—beautiful unto itself with its combination of colors and artifacts.

One of George’s chief passions was creating beautiful gardens. He loved planting unusual trees, shrubs, and flowers throughout the grounds, and carefully directed where each specimen would go. The end result was both harmony and beauty so he could enjoy God’s eternal presence in nature. The design of the house was his labor of love, and the gardens were spectacular—a masterpiece that bore his creative hand everywhere.

That was just the first of many weekends I spent there, watching as he meticulously designed both the interior and exterior of the property. Later on in our relationship, we would spend hours together planting bulbs, flowers, and shrubs while talking about India and God.

He didn’t like the business side of the music industry but unfortunately had to deal with it. One sunny summer afternoon when we were in his garden together, he got a call from Mo Ostin, the chairman at the time of Warner Bros. Records. George yelled to his assistant, “Don’t tell him I’m in the garden! I’m supposed to be in the studio recording.” That was George, putting his priorities in order: garden first and career second.

Initially, I only was aware of George as a musician and artist, along with his comical side. As our friendship developed, however, I became more aware of his spiritual side, which fascinated me. I never before had a friend so deeply interested in spiritual matters and Eastern philosophy, while at the same time be so open about it. He was very concerned for the well-being of others, often taking a personal interest in someone who was suffering. Though he was concerned about politics and the environment, he was open in his views, always pressing for spiritual solutions. He told me that me when he visited President Gerald Ford at the White House, he handed him as a gift his favorite book, Autobiography of a Yogi. He also gave him a button to wear on his jacket—a photo of a yogi master named Babaji—and not George’s new CD, as one would expect a rock star to do. I marveled at both his courage and his role as an ambassador of peace, and was so happy to have a real friend who spread the message of truth everywhere he went.

But he could also get upset with people and was open about that as well. He never beat around the bush with his feelings and was quite fearless about getting straight to the point when there was an issue at hand that he disagreed with. At first I was quite surprised by this behavior.

Inwardly, I felt it conflicted with his spiritual nature, but I began to realize that when it came to upholding principles when one was on the spiritual path, manifesting strength was very important. Self-realized masters can get stern and even appear angry if a disciple openly manifests some undesirable character trait. But in the next moment, they can instantly become loving and understanding again. I later read that to be fit for enlightenment, man must be fearless. Several times during the making of All Things Must Pass, he would get on Phil Spector’s case when they disagreed about a creative matter. I think this ultimately led to Phil being let go as producer during the making of George’s next album, Living in the Material World, which I felt was a wise move.

George was neither shallow nor superficial; his personality was deep and multidimensional. He was an amazing cook, a humanitarian, the president of Apple Records for a period of time, and a deeply caring individual and friend. But it was the gentle, spiritual side of his nature that I related to most. He was my first spiritual mentor. At that time in my life, I didn’t really have any religion, having divorced myself from Catholicism in my early teens. I had decided not to receive my Confirmation, and had guilt dreams about it but, deep down, felt my decision was the right one. I knew that there was a God, but I was alienated by organized religion, especially the guilt part of it. With George, I had a sense of soul recognition as the friendship progressed, and years later, when I became steadfast on my spiritual path, I realized I must have known him before. He was the instrument God had chosen to introduce me to my spiritual path and guru.

During the early 1970s, George began talking to me more about Indian philosophy, which he had already begun to investigate through his close friend Ravi Shankar, the Indian sitar player he met when the Beatles first visited the Maharishi in the mid-1960s. Musically and spiritually, Ravi had a huge influence on George throughout his entire life. Initially, he was George’s Indian music teacher, teaching him to play the sitar and showing him the fundamentals of Indian music. But that role expanded as Ravi began supplying George with spiritual books to read as well. Of all the literature Ravi gave him, Autobiography of a Yogi by Paramahansa Yogananda ultimately changed George’s life. He had an impressive collection of books on Indian and Vedic philosophy by the time I met him, many written by Yogananda. To me it was an uncanny coincidence that of all the books he gave me, the one that drew my attention most was Autobiography of a Yogi—a book given to my father many years earlier by Connie Markle, the mother of my close high school friend Bill Markle. Connie was very spiritual and offered me a wealth of information at that time of my life.

The book with Yogananda’s face on the cover sat in our living room bookcase near my father’s easy chair in our New Jersey home. My dad would sit reading it—slowly shaking his head in amazement at what he was taking in, or letting out a “wow” every now and then. Still, I never read it until years later, when George handed it to me as a present. “He’s the real thing,” George told me, and he clearly felt a true connection—especially since Ravi had given him the book initially. “When I first saw the cover of the book with Yogananda’s picture looking directly at me, I felt like I was getting zapped, especially with those penetrating eyes,” he told me one day.

I had the same feeling when I rediscovered the book for the second time in my life, at a point when I was ready for it. As I read it, I was transported to another place and time. Every page was beautifully crafted, like poetry. The deep truths resonated within my heart and soul, illuminating questions I had pondered over the years. I felt I had come home at last.

Even though English was not Yogananda’s first language, still he expressed himself brilliantly, elucidating perfect words for each idea. One of his disciples related a story that when she was taking dictation on a book he was writing, he used a word she’d never heard before. She tried to correct him, but he insisted it had to be right, since what he was writing was coming to him directly from Spirit. After searching through three dictionaries, she finally found the word. It was absolutely perfect for the idea he was expressing.

Kumar Shankar, Ravi’s nephew, was initially George’s assistant and cook. We frequently enjoyed his Bengali vegetarian feasts while discussing different aspects of Eastern philosophy late into the night. George was in his element at those times, and the depth of his knowledge amazed me. The more I listened and asked him questions, the more animated and delighted he became, mentoring me on what he knew. Throughout Friar Park were photos of the line of gurus that Yogananda came from, and many times while walking past one of the photos, George would stop and give me his insights. “Now, this one’s name is Babaji and he’s really far out,” he explained to me one evening. “He lives in the Himalayas with a small group of disciples and is perhaps thousands of years old. He maintains a youthful body and is mostly in a state of ecstasy, sending out peaceful vibrations to the rest of the world so that we don’t blow up one another.”

In his autobiography, Yogananda said of Babaji, “That there is no historical reference to Babaji need not surprise us. The great guru has never openly appeared in any century; the misinterpreting glare of publicity has no place in his millennial plans. Like the Creator, the sole but silent Power, Babaji works in humble obscurity.”

“How incredible,” I thought. “There are yogis who actually meditate, pray, and are deeply concerned with the survival and well-being of our planet.”

It all made total sense to me, and over time I began to release a lot of fear I had been living with for years, especially the fear of death, which was a big one for me. While in high school I had written a paper on the Upanishads, an Indian scripture, and for the first time became fascinated with the concepts of reincarnation and karma. Though I did not yet have the knowledge I now possess about Indian spirituality, even then I sensed that life was the soul’s journey toward perfection. Slowly, lifetime after lifetime, we work out all the kinks we carry with us until we finally attain liberation, never needing to reincarnate again, unless we willingly choose to do so to help others still struggling for release. I could never buy into the idea that there was only one chance, and if you didn’t make it to heaven, you would burn in hell or purgatory for a while—or for eternity if you were really bad! Slowly my deep uncertainty about the purpose of life and death I had had since my near death experience began to clear up, and over time the fog of ignorance slowly lifted. I still wasn’t 100 percent fearless, but at least I could finally see and feel a way out of my dilemma. It is marvelous that the events we attract into our lives trigger exactly what we need to work on in this present incarnation—mine is fear. But God through his Compassion never tests us with more than we can bear. I often wonder if, just before I incarnated in this present life, an angel in the astral heavens asked me, “OK, do you want light fear, medium nightmarish fear, or megaterror to work on in this next life?”

“I’ll take the medium, with an option to go light if I need to,” I answered.

Initially, George was searching for a living guru, whom he never found, but toward the end of his life he became a disciple of Yogananda, who had left his body consciously in 1952. Leaving the body consciously is a feat only a fully liberated master with no more karma can accomplish. Such yogis know beforehand the precise moment of their exit from their bodies and gracefully leave, withdrawing the life force from their bodies into and up the spine and finally exiting through the through the Kutastha, or spiritual eye, the reflexion of the medulla oblongata, which is at the base of the skull.

Yogananda’s exit was quite beautiful and took place at the Biltmore Hotel in Los Angeles on March 7, 1952, at a dinner honoring the Indian ambassador to the United States. When it was time for Yogananda to speak, he talked about India and where he first found God. At the end of his talk, he recited a poem he’d written, called “My India.” The last lines of the piece read: “Where Ganges, woods, Himalayan caves, and men dream God—I am hallowed; my body touched that sod.” He then slumped to the floor, to the amazement of his audience, having departed this plane of earthly existence. Many lives were changed that evening, profoundly moved by what they had witnessed. His body lay in state and showed no signs of decay, incorruptible for more than thirty days after his passing—astounding morticians from Forest Lawn Mortuary who confirmed the case.

God realizes masters are more alive and present than you and I, and are constantly helping and silently directing those who are in tune with them. Having a guru in a body does not necessarily help a disciple advance spiritually. During a trip to India, while still with the Beatles, George met Maharishi Mahesh Yogi, who became his teacher for a while. He then got involved in the Krishna Consciousness Movement, which was when I met him, and helped support the organization in the U.K. and elsewhere in the world. The Krishna Movement stresses continual silent chanting of the Hare Krishna mantra in order to keep the mind focused on God. Over the years, I observed that George had a broad view of the teachers and spiritual leaders he met during his spiritual journey. I don’t remember him ever openly criticizing or judging any of them. We both shared the view that when you’re ready to start out on a spiritual path, God sends you a teacher or even several teachers with different degrees of realization till you’re ready to move to a higher level of spiritual instruction. Ultimately, when one has sufficiently advanced and has learned to control the mind and emotions, God sends a fully liberated master to bring that soul back home where He abides. George often told me how he would love to spend the later part of his life living in India, in the holy city of Banaras (also known as Benares or Varanasi) wandering along the banks of the Ganges. When we later went to India together, I saw firsthand what a profoundly beautiful idea that was.

In 1971, I decided it was time to record another solo album, which became Footprint. George had started to take an interest in helping me in my career and offered to produce my first single, “Stand for Our Rights,” using the name George O’Hara in the credits. During that time, record companies forbid their well-known signed artists to use their names in the credits of other artists’ recordings. We used a lot of the same musicians from All Things Must Pass for the single, including Jim Keltner and Jim Gordon on drums, Klaus Voormann on bass, Jim Price and Bobby Keys on brass, and Jerry Donahue, Hugh McCracken, and George on guitars. Sonically, it echoed a bit of the Phil Spector production from All Things Must Pass—especially with two drummers and three guitarists. George’s creative contributions were wonderful—especially the brass parts and backing vocals. Andy Johns engineered the sessions and we recorded it at Olympic Studios. After we laid down the basic track, we came back the next day and added backing vocals, using P.P. Arnold, Madeline Bell, Barry St. John, Liza Strike, and Doris Troy. At the end of the session, when we listened back to all we had laid down that day, I was sure I had a smash hit. But the icing on the cake was yet to come.

Reprinted from Dream Weaver: Music, Meditation, and My Friendship with George Harrison by Gary Wright with permission from Tarcher/Penguin Random House. Gary Wright, 2014

You can catch Wright performing at the City Winery in Napa on Oct. 4, as well as the City Winery in New York City on Oct. 19.