The slow, bewitching beginning of the opening section of Sarah Waters’ latest novel, The Paying Guests (published by Penguin), is its own perfect deception: What seems to be a quiet, domestic novel set in suburban London in 1922 gives way to a shocking and moving page-turner about an illicit lesbian love affair, murder, and sensational trial.

There will be as few spoilers in this article as possible. You will want to savor The Paying Guests: phone off the hook, cushions plumped, the whole delicious book-reading isolation routine.

When I meet the outwardly unassuming, charming, and youthful-looking Waters at the beginning of her U.S. tour over saffron risotto (her) and swordfish (me) at Vice Versa restaurant in midtown Manhattan, I ask first whether The Paying Guests is a crime story, a love story, or a historical novel?

“I think love story at its heart,” Waters says. “I was writing part one over and over again, and it wasn’t going right. I was thinking of it as a romance, a very small story. Then I realized that even though in my other novels love and desire are strong elements, I’d never written a love story before, with the two characters tested. That crystallized it for me: The crime would push and test them. This is a love story complicated by crime.”

It’s Waters’ first novel set in the 1920s. The bestselling author, whose novels are published in 30 languages, made her name with a series of books set in Victorian times with lesbian desire at their heart, most famously, her award-winning first novel Tipping The Velvet (1998), which was made into a sexy, rollicking, brilliant BBC drama series; then Affinity (1999), and Fingersmith (2002).

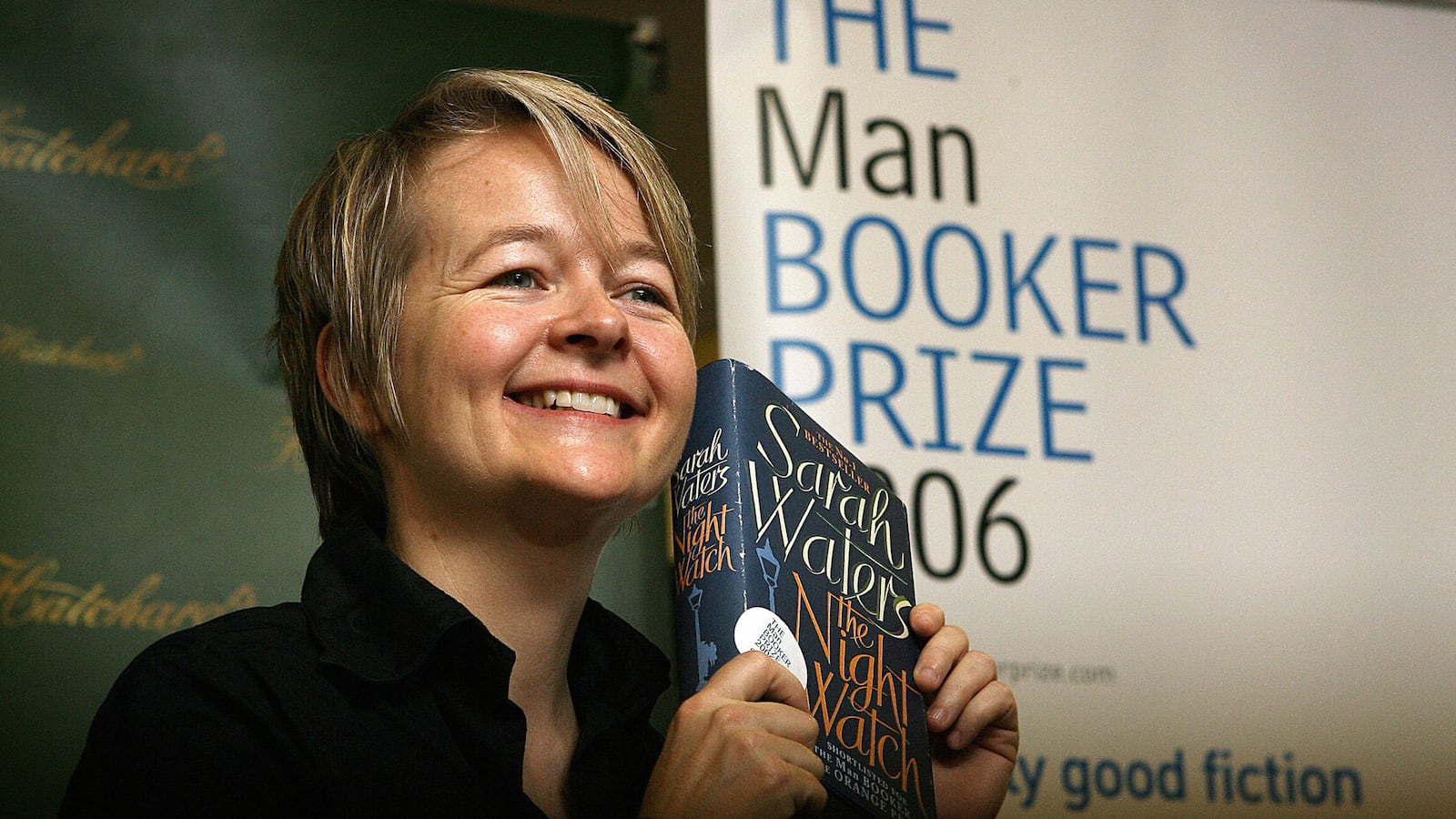

The Night Watch (2006) placed her characters in the orbit of World War II, while the non-gay—but still queer in the widest sense of that word—The Little Stranger (2009) was a wonderfully creepy, and moving, ghost story. All of the books have won or been nominated for awards; the last three for arguably the most prestigious award of all, the Man Booker Award for fiction.

Waters, 48, is the maestro of the tortured lesbian romance: Her couples overcome obstacles and then some, confessions of feelings are voiced tremblingly with so much at stake in times when homosexuality was so proscribed, and little understood. Waters places lesbian sexuality into historical contexts where, in popular fiction, it has been mostly invisible and never the prime focus of the action.

The Paying Guests is about a mother and daughter, Mrs. Wray and her daughter Frances, who take in the “paying guests” of the book’s title, the married Leonard and Lilian. The post-war London that Waters uncovered in her thorough research is far from the “Roaring Twenties” of popular imagination, but straitened and unnerved by enduring the First World War.

Waters’ readers know how she stealthily builds detail and quiet subversion into her novels; an accruing sense that even in the most conventional surroundings—in this case a fusty and respectable suburban house—the very opposite of convention threatens to rupture the silence and change lives. And so it is that Frances and Lilian fall in love, and, from that, (very thrillingly written), all hell breaks loose.

“I read newspapers from the day, court transcripts,” Waters says of her research. “I read about how crimes were dealt with. It was such a complex, murky period; people coming out of war feeling the world was unsafe, ex-servicemen were on the streets, disgruntled; men and women were at odds.”

Her novels typically evoke this pinched sense of an era—raw individuals in raw times.

“Well, conflict is good for novels, and the 1920s speak to us now,” Waters says. “Ours is a world which feels so unsettled and dangerous in large ways, whether it’s terrorism or global financial meltdown or climate change—huge things that affect us deeply, and yet things about which we can do, individually, very little. In the novel, the moral situation Frances ends up in is dreadful. Like in The Night Watch, I’m interested [in] people’s cowardice and bravery, the times when things that are asked of you are so big you can’t not be a coward—how to behave well in a complicated world.”

The Great War’s shadow is tangible throughout The Paying Guests. “I stupidly hadn’t thought how close the early 1920s were to the war,” the novelist says. “They appealed to me because they were such unhappy times: all that loss, turmoil, politically things were very unstable, there was a lot of bad feeling. The literature of time is completely riven through with discontent: writers like Oliver Onions, and A.S.M. Hutchinson, whose If Winter Comes (1922) is about a decent man struggling with the corruption around him. There was E.M. Delafield and Katherine Mansfield. It’s not that these themes aren’t present in writers like Woolf, but the writers I mention are much more accessible in terms of human drama and the detail of the times they use.”

In The Paying Guests, the house, which creaks and stands so still and yet so freighted, is almost a character in itself.

Waters smiles. “I liked the idea of the house, that mother and daughter had lost their menfolk to war, that they needed money and to have these strangers in their home. I’m very interested in the nitty-gritty of domestic life. Frances is always doing housework. The house becomes a very charged place. In a shared house there are all those fraught spaces, threshold spaces, like the staircases and hall. They become even more awkward when an affair starts. Our stereotype of the ‘Roaring Twenties’ is cocaine, nightclubs, and flapper girls. I wanted to know what was going on in ordinary people’s lives.”

Camberwell (in South London) was still seen as suburbia in the 1920s. Champion Hill, where the book is set, is two quiet roads of genteel-looking houses, first settled in the 18th century. The book, like its setting, begins quietly, then there is a murder which in her planning was Waters’ jumping-off point.

Waters was inspired by the case of Edith Thompson and Frederick Bywaters in 1922. Thompson was a lower-middle-class businesswoman married to a man named Percy, who had an affair with a young man, Bywaters. “They wrote each other letters, she talking very engagingly about her life, unhappiness, and sexual desire,” Waters says. “She got pregnant and took something to get rid of the baby. She flirted with the idea of killing her husband. If there was a murder case in the paper she cut it out and sent it to Freddie. Finally, after some kind of confrontation, Freddie stabbed Percy to death.”

Thompson claimed not to have known what had happened. Bywaters was arrested, the letters were found, and she was charged with incitement, put on trial, found guilty, and hanged for a murder she technically hadn’t committed. “People were very against her,” Waters says. “They felt she had corrupted the young man. It was the crime of that period: gender, class, the suburbs, were all there. Later, people felt very uncomfortable that she hanged, it’s now seen as a miscarriage of justice. The transcripts of the trial are amazing. I began to think, ‘What if the lover were female?’ How would that affect aspects of the case? I wanted to think through what emotional impact a murder would have on the relationship.”

Waters’ books cleverly, humanely, and non-didactically, weave lesbian sexuality into long-past history.

“You can go to any historical period, and what we know of it tends to be rather heterosexual. I’m interested in stories that aren't getting told: it’s where my interests lie,” the novelist says. “It seems more natural to me to write about lesbian characters than straight characters, being one myself—not that I haven't written about straight characters, but I like complicating the historical stories we have.”

The Paying Guests is different than Waters’ Victorian novels; the 1920s was a time when lesbians were beginning to connect more openly: Frances meets her ex-lover via the pacifism movement, for example.

“Moving into the 1920s, we know there were lesbian networks and communities,” Waters says. “Authors like Marie Stopes were talking about it. Daphne du Maurier and her sisters all seem to be raving lesbians—they were all having affairs with women when they were quite young. In some circles of the Bohemian upper classes it seems to have been a fact of life.”

But there was no proto-lesbian scene as such? “It was much more domestic for women,” says Waters. “Gay men’s sexuality has always been played out more in public—bars, cottages (tearooms). Women may have frequented bohemian bars, but on the whole it was friendships and private networks. I wanted Frances to be completely confident about her sexuality. It’s not a problem for her. I wanted her problems to come from other things. She is the last generation of spinster-daughters expected to stay home and look after her parents. So she’s sort of trapped, yet has this transgressiveness about her.”

I say it must be odd to write in modern times about times when there were no words or free-flowing discourse around these things. No, Waters laughs, that’s the fun of it. “What’s exciting about writing historical fiction is trying to capture that strangeness of there not being a word for ‘it,’ which has so many words today. Frances does have a community, and is vocal, Lilian doesn’t. I’ve never written about a straight woman before.”

Was that difficult? “I asked my lesbian friends if any of them had had affairs with straight women, and if so what issues they faced. Quite a few said they felt unsafe in the relationship with the straight woman and messed around with—like the straight woman was dabbling around a bit. That stayed with me—not because I wanted Lilian to be a dabbler but because it might lead to insecurities that Frances might have; that at any moment Lilian might step back into her marriage.”

Has Waters ever had an affair or relationship with a straight woman? “No, but interestingly it was Lilian I think back to when I was 19, when I was straight, living in a lower-middle-class home, wanting to be arty, collecting all these scarves and things, filling my room as Lilian does. At that age you can fashion yourself: everything is up for grabs. You’re open to all kinds of things, and Lilian allows herself to fall for Frances.”

So she wasn’t gay, or gay-defined, or out, when she was younger? “I had a boyfriend, although he then came out as gay in that classic way that happens when you’re both gay. I liked the idea of being bisexual and then met a girl who had a bit of lesbian experience and got together within a few months. It was fantastically alarming and exciting. We were together for several years. It was 1985. It seemed like an enormous statement to be making about yourself, and just to be attracting that much attention was daunting.”

Waters grew up in Pembrokeshire, Wales, “very ordinary: dad an engineer, mum a housewife. Quite a bookish, not rich family. At the library I read lots of sci-fi and horror—I loved The Tripods (by John Christopher)—never the children’s classics. I was quite a tomboy. I never read Mallory Towers, or anything like that. I was quite academic.”

The now-novelist grew up wanting to be an archaeologist without knowing what that meant. “I used to write at home, but it didn't ever occur to me to be a writer. I don’t remember writers being personalities like they are today. They were just a name.” She studied English at university, worked in a bookshop, then as a library assistant. “Missing” being a student, Waters went back to university (Queen Mary in London) to do a Ph.D. in lesbian and gay historical fiction.

She became, like me, a huge supporter of Gay’s The Word, Britain’s now-only lesbian and gay bookstore.

“There was so much lesbian historical fiction around,” she recalls. “Patience and Sarah, Ellen Galford’s Moll Cutpurse, Her True History. Chris Hunt’s Street Lavender is raunchy fun, but also really clever about the formation of gay identity in the 19th century.” She also read Philippa Gregory, A.S. Byatt, Peter Carey, and Peter Ackroyd.

When Waters herself is writing historical fiction, how immersed is she in the period? “It does hang around in my head,” she says, smiling. “The 1940s has a strong identity in our heads, but the 1920s is more of a flux. It was hard to get a handle on. I read lots of diaries, letters, and newspapers. I treat writing like a job. I write from 8:30 a.m. to 4:30 p.m., and when I turn the computer off, I sit down and read from that period for an hour or so. I do love the past, but wouldn't want to live in it. The books are not nostalgia, and I would hate for them to be thought of as nostalgia. Things like sexuality feel so inherent and essential, yet they are historically contingent.”

I say that I see her books as queering the past, not just with homosexuality, but generally—she takes historical periods we have certain ideas about and re-customizes them.

“I like writing about ordinary, unknown lives, rather than well-known historical figures,” Waters says. “I never wanted to do that. I feel oddly squeamish about it. I like writing about those who have left no mark on history in that way—people who get overlooked.”

She herself started writing “with no great ambitions at all. That’s what enabled me to write. If I’d had huge ambitions I would have been paralyzed. I felt a community of lesbian readers might find Tipping The Velvet fun. I wanted it to be published, but had no vision beyond that. Writing it made me realize how much I love writing.”

Waters became really famous after Tipping The Velvet was made into a TV drama in 2002. “It was fantastically exciting,” she says. “I had a bit part in it, which was a lark. I do remember feeling daunted the next time it came to write a book: there was an audience waiting, and I knew it would get the kind of scrutiny the other ones had not. When I wrote The Night Watch, moving to the 1940s, it was the only time in my career I ever remember feeling anxious about what I was doing. The Paying Guests was challenging too: I thought, ‘Should I turn it into a caper?,’ like Bound, but then I realized I wanted to do something true to life and dreadful, to capture the devastation. It took a lot of work to get it right.”

And, hallelujah, I say: The lesbians don’t snuff it in your books. They’re not punished by being made to die, or be bereft and alone.

“I was very conscious of that older literary tradition,” she says. “But when I started reading, it was a lot more positive. Jeanette Winterson was writing this lush lesbian fiction. Years before I even thought of writing, I remember picking up The Passion, and being so impressed that this was a lesbian story not published by one of the smaller presses but by a big publishing house. Alan Hollinghurst’s The Swimming Pool Library was also lush and literary.”

Your Victorian lesbians were sexy, vocal, recognizable, and radical too, I say. She is far too modest to capitalize on my cheerleading. “I suppose there was something new about it, there hadn’t been many lesbian sex scenes before. But in the mid-1990s lesbianism didn’t seem a big deal. I was living in the lesbian community, there were lesbian bars. There was Diva magazine, ‘lipstick lesbians,’ and the women’s sex-toy shop, Sh! All my lesbian friends were talking about dildos. It was a kind of upbeat time.”

Did she have a wild London life? “Oh god no. I lived in a lesbian-shared house in Stoke Newington (a district in North London, stereotypically popular with right-on lesbians, particularly back then). It was lots of fun.”

As for girlfriends and partners, Waters says she is a serial monogamist. She went into that shared house with a girlfriend, Kate, and came out with another girlfriend, Laura. “There were a couple of crushes in between, and I was with Laura for seven years. It wasn’t wild but it was fun.”

Waters has been with her partner Lucy Vaughan for 12 years. They met at a mutual friend’s house, and had a civil partnership ceremony three years ago, “to be honest for fairly pragmatic reasons: making wills and such. We’d just moved in together and it seemed the sensible thing to do.” She smiles, and laughs. “Once we did it, it became incredibly romantic, much more romantic than I expected—lovely, in fact. We had the tiniest possible ceremony: just us and two friends. We went to a cafe for lunch, then Lucy’s parents for some cake, then took the ‘sleeper’ train to Edinburgh, and hired a car and toured the west coast of Scotland.”

Will the couple, who live in Kennington, South London, go for full marriage now they can in the UK? “No, we’re happy with a civil partnership. It’s oddly like being part of that particular historic moment. We talk about it as if we were married.”

Having children was never something Waters wanted to pursue, “and I’m getting to that age now where I wouldn't want or be able to have kids that much longer. Getting to that age does make you think, ‘Oh, I’ve never wanted them but now time really is running out.’ It’s a bit weird, but that would be the worst reason in the world to have kids.”

Waters herself is a gay figurehead, but again she shrinks from any compliments. “It’s not like I’ve really done anything new, but my books have accompanied an incredible shift in the UK around equality. For lesbian readers there’s an extra political element that I totally understand, and feel the same thing.”

So she has groupies? “Not really. But what is weird is getting messages from different parts of the world where things aren't so great—from Korean lesbians who’ve read pirated copies of the books, or Russian lesbians or even in Italy, where lesbians are clearly feeling very beleaguered and under-represented, and Poland too.”

She pauses. “It’s quite sobering going from the happy UK, where there are lesbians on telly every five minutes, and we have equal marriage and other legislative protections, to go to another part of the world where things are very different. Even in the UK, although we are equal under the law, homophobia is still a problem. At Gay’s The Word, their first job in the morning is to clean the spit off the windows.”

There is so much romance in her books, I ask if she is a romantic herself, if love is important to her.

“Yes,” she assents carefully, “in the sense that it’s something that makes us human: the capacity to make a connection to other people, the capacity to empathize—we lose those at our peril. Intimate relationships are an extension to that. I think Lucy would probably say I’m not a romantic.” She laughs. “I’m interested in the way that love is a mixture of other things. Love often contains fantasy, projection. Love can seem so solid yet can be de-stabilized so subtly. I’m talking as a novelist, but you can’t take anything for granted in your life and neither should you.”

The book becomes so dramatic and twisting, the ending—how she ends it--is key. I won’t spoil that for anyone. It does end, dramatically, on a bridge. “They’ve spent much of the novel indoors I wanted them outside,” says Waters. “I’ve always liked these little alcoves on Blackfriars Bridge, and the River Thames.” Waters loves walking the city’s streets, which is evident in all her books.

When asked what she is working on now, Waters says she is taking “an enforced break from writing. It’s good. This book took four years to do and a lot out of me—as long as any book has ever taken me. For the next book, I may write about the 1930s. I’m being Zen and not really stressing about it.”

Would she ever write a novel set in the present day? “I might do it if I found the right story. I’d quite like to write a modern ghost story.”

As she ages Waters is aware of having less energy than she used to. “I’m very conscious about being middle-aged in some good ways. I think I’ve always been middle-aged, really.” She laughs. “Now I just can be.” Will 50 be a “moment”? “Not really. I measure out time in books. The weird thing about getting older as a writer is thinking how many books have you got left in you. How many books can you reasonably write if it takes you 10 years to write two and a bit books? That means by the time I’m 60 I’ll have written three more books if I’m lucky. Will I want to write three more books? You never think about these things when you start off as a writer.”

So, can she foresee stopping writing? “I think I will stop writing if I run out of books to write. I also have an optimism about storytelling. There are always stories to tell—it’s a question of finding the right story. It takes me a long time to write books because I have to find that story, think about it from different angles, and be happy to stay with it for several years.”

We will see more of the books on screen. The Little Stranger is being made into a feature film, and there are plans to film a Korean Fingersmith by Park Chan-wook, the director of Oldboy. “All TV and film adaptations have their strengths and weaknesses,” Waters says. “My favorite was Fingersmith, which they did in three hour-long parts, which felt leisurely. The Night Watch felt squashed, which was disappointing.”

In all your books, you’ve endowed the past with a sense of unease, I say. You’ve subverted the notion of known, fixed history—of things being simpler “back then.”

“Yeah, I hope so,” Waters says. “I think the worst thing you can do to the past is turn it into period drama—as much as I like Downton Abbey.” She laughs. “The past is so much more complex than that show would have you believe. Weirdly though, because of shows like that, we are more attuned now to servants’ lives and that sort of thing. It’s the complexity of the past that’s important to keep in mind. Crucially, it’s not modern people in fancy dress. It’s people whose loves and stories have emerged from a historical period that was very different from ours, but was as complicated, in transition, and dislocated as ours is now.”