For nearly two thousand years, religious groups have held a monopoly on how to teach morals to young children. Now Me & Dog, a new children’s book by Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist Gene Weingarten and illustrator Eric Shansby—both of The Washington Post—steps into the competitive arena of nighttime reads (6-8 p.m. division) with an atheist lullaby.

Cue sincere hand wringing: Won’t somebody please think of the children?

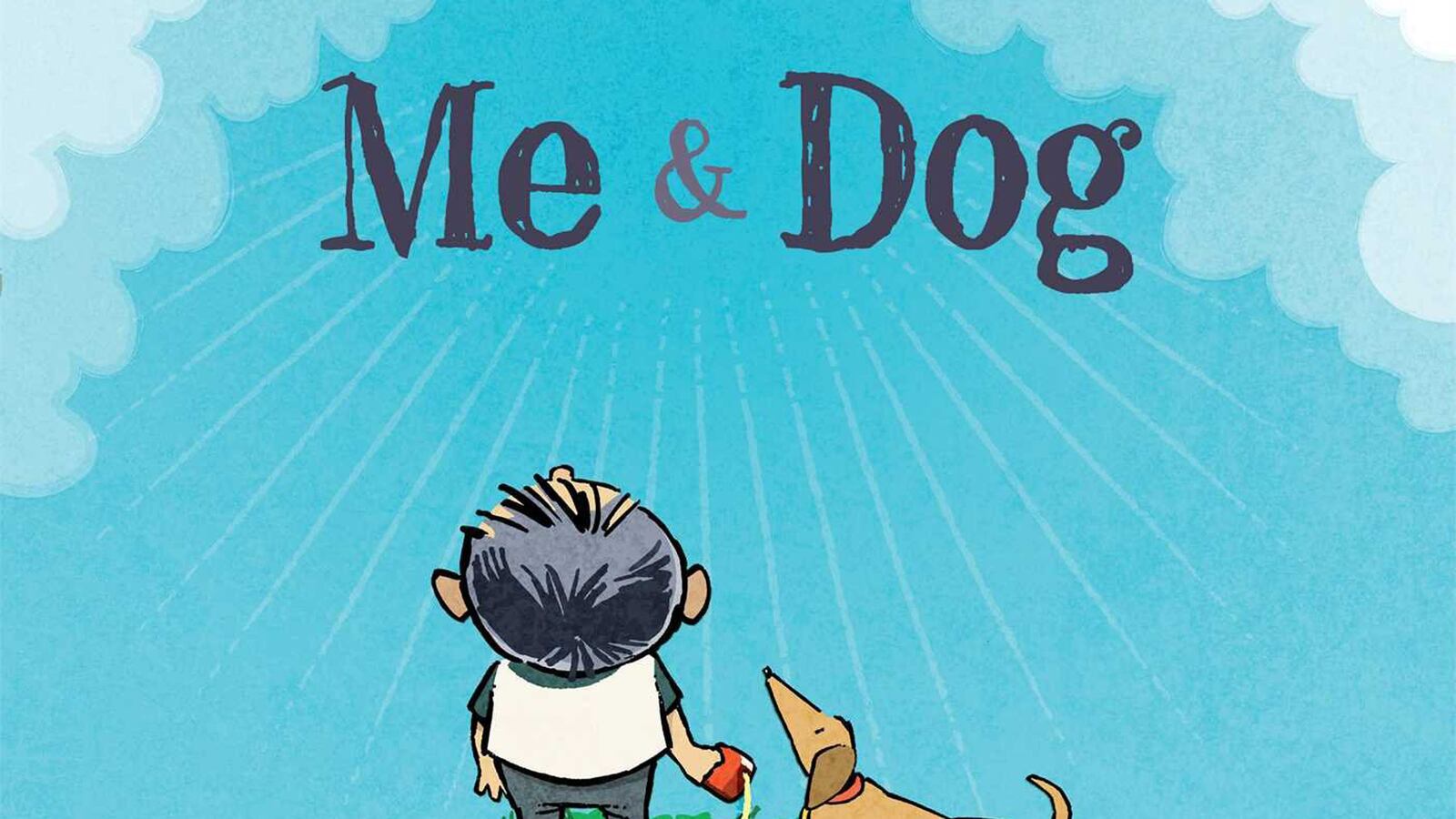

The setting for this shameless piece of atheist propaganda (you can quote me on that, religious right) is a walk between a young boy named Sid and his dog, Murphy. The young boy accidentally treads on the dog’s tail, causing the dog to instantly apologize for whatever he had done to deserve this punishment. The child’s realization that the dog thinks he’s a superhero leads to a fun, beautifully illustrated exploration of the problems of the canine condition. They think we’re all-powerful deities when actually we’re just a bunch of klutzes.

Weingarten told the Daily Beast that the book is “part parable, part narrative,” adding, “I don’t want to sound messianic, but I think there is a need for this book.” There are hundreds of children’s books written with the intention of helping toddlers take their first wobbly steps on the straight and narrow, but there are no books about atheism for children. This book seeks to fill that void (although arguably atheist kids should get used to nothingness sooner rather than later). It’s the antidote to sentimental stories about people riding butterflies in heaven. It’s Everybody Poops for the humanist set.

Like all good scripture, Me & Dog can be read literally as well as metaphorically. Weingarten told me that some people just read a book about a boy and his dog. For those who have eyes to see, though, there’s something more.

And with this first step he takes on a humdinger of a theological problem: Why do bad things happen to good canines? Or, you know, people. This is the sine qua non of atheist reasons to doubt God: it’s theodicy for the kindergarten crowd.

But it’s gently done. The humanist parent seeking to get their kid to sleep shouldn’t worry that their child will be up all night in the throes of an existential crisis. I don’t want to give away the ending, but let’s just say there’s nothing to be afraid of here.

For religious parents concerned that teaching humanism to kids might turn them into psychopaths, this is a very gentle book. There’s no genocide, rape, or mutilation here. For that you can stick with Bible. (For what it’s worth, the early Church father John Chrysostom recommends that you begin with the stories of violent divine judgment and circle back to Jesus in due course).

Historians will be reassured that there is a historical Murphy. The book was inspired by an incident involving Weingarten and his own dog; the main difference is that the historical Murphy is a girl. Which makes sense—the systematic erasure of important female figures from a faith’s history is an important rung on the ladder to success in the religious marketplace. If history has anything to teach us it’s that religious groups do better when they keep women out of things. Well played, Weingarten, well played. Me & Dog is off to a promising start and Mary Magdalene has some canine companionship.

Despite its premise, Weingarten isn’t against magic in children’s lives. His children believed in Santa until the age of five and his daughter engaged in protracted negotiations with a Tooth Fairy named Fred.

Weingarten hypothesizes that his daughter was wise to Fred’s hidden identity the whole time. The correspondence was a sort of self-aware magical joke. This, ultimately, is where he wants us to end up: It’s okay not to believe in God. It’s also okay not to shove Him down people’s throats.

The pedantic scholars among us might wonder if the book does its job. After all, in the story the child does have the power to reward and punish the dog. The dog isn’t imagining the existence of the powerful god-child; it’s that the child is just not as good, or powerful, as the dog imagines. As Weingarten told me, “There is a God. … But he’s hugely flawed, has terrible judgment, and does awful things for no understandable reason.” In other words, he’s Marduk—the ancient Mesopotamian deity who causes a flood because human beings are too noisy. When asked if Sid is actually Marduk, Weingarten agreed that he’d accept that analysis.

If it seems like we’re going backward to ancient Mesopotamia, we should note that this is actually just a first step. This book is only the “beginning of a conversation” with children about religion. Perhaps in its sequel Weingarten will scrap Sid entirely and we’ll be left with the realization that there is no dog but dog.

Me & Dog by Gene Weingarten and Eric Shansby is published by Simon and Schuster and is best digested with a glass of warm milk and the sounds of John Lennon’s “Imagine.”