Of the more cinematic, historic moments from Martin Luther King Jr.’s biography—the “I Have a Dream” speech in 1963, the Nobel Peace Prize in 1964, the Selma marches in 1965—the only one from the last year of King’s life is of the balcony of the Lorraine Motel in Memphis where an assassin’s bullet ended his life. History has largely obscured the year that preceded.

After President Johnson signed the Voting Rights Act in August 1965, King shifted his focus from upending discrimination in the South and pushing Congress and the White House for federal civil-rights protections to a broader push for economic, educational, and housing equality in Chicago. King spent all of 1966 and into 1967 leading the the Chicago Freedom Movement with only limited success.

On April 4, 1967—a year to the day before he would be gunned down—King stepped to the podium of the Riverside Church in Manhattan and told the capacity crowd of 3,000 people assembled there that every American serviceman drafted to go to Vietnam should declare himself a conscientious objector and boycott the war.

“I knew that I could never again raise my voice against the violence of the oppressed in the ghettos,” King said, “without having first spoken clearly to the greatest purveyor of violence in the world today—my own government.”

Although warmly received by the audience—the event had been sponsored by a group called the Clergy and Laymen Concerned About Vietnam—the speech was met by nearly universal derision beyond Riverside Church. The national media chided King for straying too far afield from his mandate as a civil-rights leader, many black leaders distanced themselves from King’s stance, and many of King’s own advisors in the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) had cautioned him against protesting against U.S. involvement in Vietnam.

“This year after Riverside, the hate and hostility, like the war in Vietnam that [King] so passionately opposes, will escalate to even higher and more dangerous levels,” write Tavis Smiley and David Ritz in their new book, Death of a King: The Real Story of Dr. Martin Luther King’s Final Year, a gripping, up-close, and often unflattering portrayal of King during the last year of his life.

Smiley is a PBS talk show host who has written several previous books about the African-American experience. Ritz is a biographer and frequent celebrity co-writer who has written with Ray Charles, B.B. King, and Etta James, and author of the forthcoming Respect: The Life of Aretha Franklin.

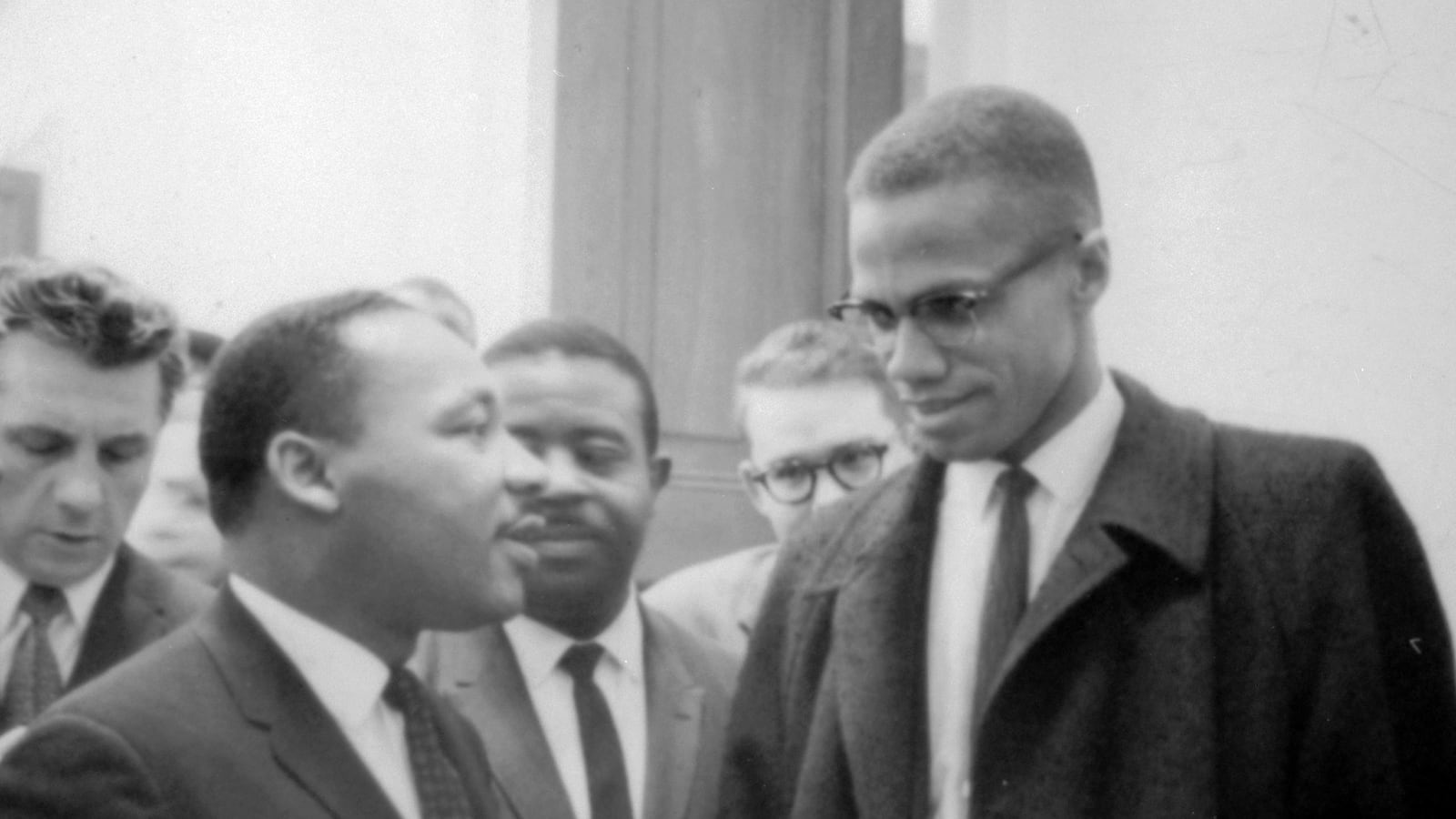

Smiley and Ritz find a fallibility and humanity in King that is more difficult to find a few years earlier when King is the central figure of the civil-rights movement. During the last year of his life, King is old news, lampooned behind his back as “the Lawd!” by others in the civil rights movement, and upstaged by younger, more strident figures like Stokely Carmichael.

By the summer of 1967, the cities are burning. Riots range in Detroit and Newark and Los Angeles. King’s new book, Where Do We Go from Here: Chaos or Community? is a flop. He has lost all influence with the Johnson administration. The civil-rights movement is either over or splintering. Nonviolent resistance is out; black power is in.

King is fighting with his closest advisors in the SCLC. He wants to continue to speak out against the Vietnam War and take on a major “March on Washington”-style event to raise awareness of poverty. He’s not sleeping. He’s depressed. “I don’t want to do this anymore!” he says at one point. “I just want to go back to my little church!” By January 1968, King decides to focus his attention on poverty by having a Poor People’s Campaign in the spring.

“What does it profit a man to be able to have access to any integrated lunch counter when he doesn’t earn enough to take his wife out to dinner?” King says in a sermon a month later at Tabernacle Baptist Church in Selma, Alabama. “What does it profit a man to have access to the motels of the highways and the hotels of the cities and not earn enough to take a vacation?”

The end of poverty is the great issue of King’s life—it’s the reason for the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965; it was, in fact, the stated purpose of the 1963 March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom—and the fact that it remains elusive weighs mightily on him.

In Smiley and Ritz’s telling, King is not gunned down vaulting toward greatness as were John Kennedy and Robert Kennedy. King had accomplished much, but his greatness was already behind him.

Memphis begins to pop up in the later chapters, and I wince at every mention because I know that is where the story will end. By the end of February, King is focusing his attention on the Poor People’s Campaign, which is planned for late spring in Washington. The suspense for the reader lies not in whether the event will go forward—it will occur in May 1968, after King’s death and beyond the period covered in the book—but in whether and how King will make sense of everything in what will be his last months.

The plight of striking garbage working in Memphis had been on King’s mind, and he finally decided to go there to march with them. The night before King was killed, he spoke of his own mortality (besides suffering from depression, he was also enduring visions of his own death). He spoke of surviving a stabbing in 1958 when a woman attacked him at a book-signing. He spoke of a bomb threat in Atlanta that very morning. He spoke of threats he had already received in Memphis.

“We’ve got some difficult days ahead,” King said in a sermon that night about the enduring importance of nonviolence. “But it really doesn’t matter with me now, because I’ve been to the mountaintop. And I don’t mind. Like anybody, I would like to live a long life. Longevity has its place. But I’m not concerned about that now. I just want to do God’s will.”

Smiley and Ritz’s book is not one of historical revelation. In his introduction and in numerous interviews, Smiley credits King biographers Taylor Branch, David Garrow, and Clayborne Carson for their scholarship, and each has written more detailed accounts of King’s life and particularly of his final year.

The worth of Death of a King lies in its story, succinctly and achingly told.